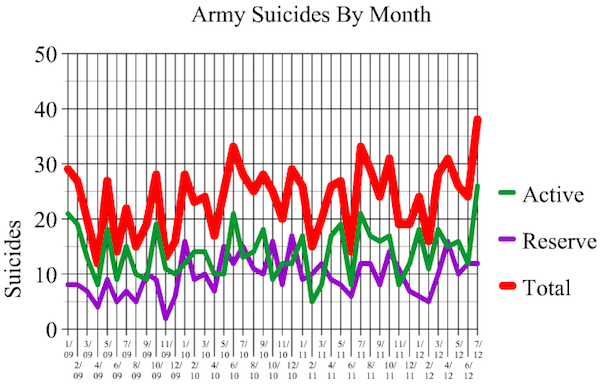

A record number of soldiers – 38 – are suspected of killing themselves in July, the Pentagon said Thursday. It marks a startling jump in the suicide epidemic that has been frustrating Army leaders for years.

The total included 26 active-duty soldiers – under the Army’s control 24/7 — also an apparent record, and a 117% jump from June’s count of 12 active-duty suicides.

(MORE: This Isn’t Funny…)

The Army has been fighting suicides when they were occurring at the rate of nearly one a day – in fact, that was the cover line on a Time story last month into the vexing problem of soldiers killing themselves after a decade of war. But July’s 38 likely suicides spread over the month’s 31 days works out to almost 1.25 suicides a day.

The toll was 58% higher than June’s 24 suspected suicides, and is roughly 50% more than the average monthly suicide count experienced over the past 18 months.

Military suicide data has only been kept diligently in recent years; non-active duty suicides have only been tracked for about five years. So that makes historical comparisons difficult. But the numbers are the highest since 9/11, and several experts believe they mark an all-time high. “The number 26 [of active-duty suicides] is the highest single month we’ve had since 2001,” Bruce Shahbaz, a medical analyst on the Army’s Suicide Prevention Task Force, told Time Thursday morning. “The combined total [38] of both active and reserve is the highest we’ve had since 2001.”

Army experts come up empty-handed when trying to account for the surge, although they are noting a shift among suicide victims. “This is the first time since 2001 where we’ve seen non-commissioned officer deaths outnumbering junior enlisted deaths,” Shahbaz says. He and other Army suicide experts have what he concedes is a “very counter-intuitive” explanation.

Battleland graphics lab based on Army data

They suggest this is happening as the NCOs — more likely to be married, and in the Army for the long haul, than younger troops — begin spending more time at home between deployments. “If you’re on the constant 12-month treadmill of deploy, reset, get ready to redeploy, deploy, soldiers and families don’t work hard to try to reintegrate, because they know that their soldier is going to be gone again,” Shahbaz says. “Issues like minor depression, anxiety and sleep disturbances – those things that are kind of related to post-traumatic stress – begin to surface after a service member has been home for more than a year, and start to reintegrate with their family…I liken it to a pot that’s on simmer – having that person stay back home and reintegrate with their family sometimes allows that pot to boil over.”

Retired Army colonel Elspeth Ritchie, once the service’s top psychiatrist and a key warrior fighting Army suicides, fears the toll won’t abate any time soon. “One of the risk factors for suicide is getting in trouble at work,” says Ritchie, now a Battleland contributor. “As the Army downsizes, the getting in trouble may translate into more soldiers facing discharge and possible unemployment,” she says. “Another risk factor is trouble with relationships. After a decade of war, going from having a spouse away most of the time — to being at home all the time — actually may make things worse. Especially if the spouse is underemployed.”

(COVER STORY: The War on Suicide?)

Those fighting the battle from outside the Army remain dissatisfied in light of the latest suicide count. “Soldiers and their families are falling apart under the pressures, expectations, injuries and illnesses of years of war,” says Kim Ruocoo, who runs the suicide outreach program at the non-profit Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors. “We should expect our troops to need psychological care after all we have asked of them, yet there is still a sense that asking for help is a weak thing and should be avoided. As a result soldiers are waiting until they are very sick before they go for help and very often the response is not quick enough or comprehensive enough.”

Retired general Peter Chiarelli, who until January was the Army’s No. officer and top suicide fighter, remained frustrated in a recent interview. “Our suicide rate has doubled since 2001, and it’s obvious that deployments and stress on the force plays a role in this –- there’s no doubt about it,” he says. “The doubling of our suicide rate coincided with our fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan. That’s got to be a contributor.”

But it’s bigger than that, he believes. Mental-health problems have never gotten the study – and the resulting research funding – given to cancer and heart disease, he says. “We’ve under-invested in this area for so goddam long, and one of the reasons is because of the stigma associated with it,” Chiarelli says. “No one wants to admit that Uncle Al killed himself.” That’s one of the reasons Chiarelli has gone back to work leading One Mind for Research, an independent, non-profit organization bringing together health care providers, researchers, academics and the health care industry to cure brain disorders.

The challenge of soldiers trained to kill turning their guns on themselves – firearms remain the method of choice for most Army suicides – has gotten the Pentagon’s attention. “This issue – suicides — is perhaps the most frustrating challenge that I’ve come across since becoming secretary of defense,” Defense Secretary Leon Panetta told the military’s 4th annual suicide-prevention conference June 22. “Despite the increased efforts, the increased attention, the trends continued to move in a troubling and tragic direction.”

“This is not just an Army problem – this is a national problem,” Shahbaz says, referring to a new Centers for Disease Control report showing that nearly 37,000 Americans killed themselves in 2009. While suicide rates for both troops and their age-adjusted civilian counterparts have been comparable in past years, that’s not the case so far into 2012: the Army rate stands at 29 suicides-per-100,000, nearly 60% higher than the civilian rate of 18.5 in 2009, the most recent available.

Shahbaz, like most every Pentagon expert on suicide, encourages anyone thinking of taking his or her own life to call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255; press 1 if you are in the military or in a military family. “These folks do amazing work,” he says of those who pick up the phone at the other end. “They are angels when it comes to helping soldiers and families in crisis.”

(READ: U.S. Military Suicide Rate Now Double or Triple Civil War’s)

Suicides have spiked since 2005, even as the war in Iraq has ended, and the conflict in Afghanistan begins to wind down. The drip-drip-drip of statistics tells the story: mental-health problems were the top reason troops were hospitalized last year, according to a May Pentagon report. Nearly 22,000 troops were hospitalized with mental disorders last year, 54% more than in 2007. Suicides, the military’s medical command noted in June, have now eclipsed motor-vehicle accidents as the leading non-combat cause of death among U.S. troops.

The specific triggers for suicide vary by individual. But for those in uniform, the stresses associated with a decade at war – and the frequent deployments and family separation they entail – play a role. Yet many troops who have never deployed also are killing themselves.

The Pentagon is training troops in resiliency to weather dark moods, establishing suicide hotlines, bolstering its ranks of mental-health workers on the battlefield and at home. The Army has launched a $50 million investigation into the suicide surge and how to stop it.

“Our people are our most valuable resource and we are very committed to taking care of them,” Jackie Garrick, who runs the new Defense Suicide Prevention Office, told Time recently. “We just need to make sure that we’re getting that word out, and the services and the service members at all levels are fully engaged in trying to address this issue.”

But, Chiarelli insists, it can’t be done without more research and resources. “We have a crisis in the military,” he says, caused by a lack of money and knowledge to deal with the mental-health challenges created by 10 years of combat. “We just don’t know enough,” he says flatly. “And until we do, we will all remain frustrated.”