While the Pentagon is trying to cool down the rhetoric with Tehran (“We seek to lower the temperature on tensions with Iran,” Pentagon spokesman George Little said last week), not everyone has gotten the message, apparently. Perhaps that accounts for the independent Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments’ release Tuesday of a detailed study showing how the U.S. military should ready for military action there (click on the map to enlarge).

Authors Mark Gunzinger and Chris Dougherty, in what they label as “an important caveat,” say “there is no intent to imply that conflict between the United States and Iran is inevitable.” But then they helpfully go on to explain how the U.S. military might reverse Iranian action to shut down the Strait of Hormuz:

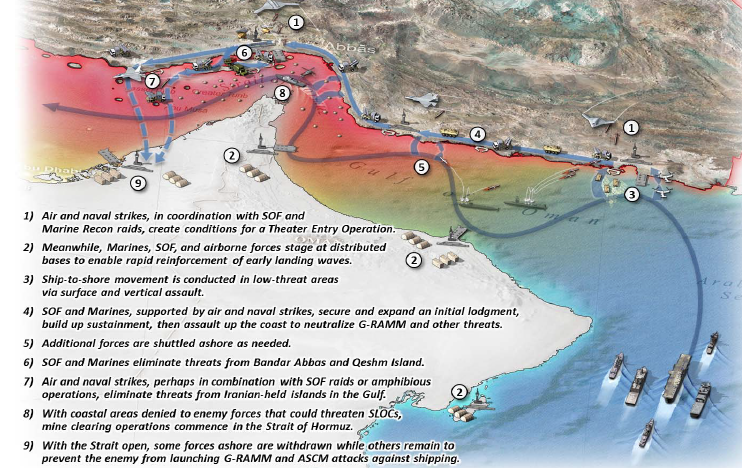

Executing a Joint Amphibious Landing.

…a force of two Marine Expeditionary Brigades (MEBs), supported by SOF [special operations forces] and possibly Army airborne and air assault units, could seize and hold a lodgment at a time and location of Central Command’s choosing. An objective area for an amphibious landing should be located where enemy A2/AD [Anti-access/area-denial] threats have been suppressed, and may not be in proximity to “existing ports, airfields, and logistics infrastructure.” Immediately after landing, SOF, Marine Corps, and Army forces would concentrate their efforts on expanding their operating perimeter and preventing the enemy from closing within range to use G-RAMM [Guided-rockets, artillery, mortars, missiles] weapons. Non-lethal capabilities and mobile high-energy laser weapons could help deny hostile forces access to key areas and create a defensive “barrier” against G-RAMM attacks. U.S. forces could then use this secure lodgment as a jumping off point for follow-on assaults up the coastline of Iran to clear areas that could be used by the enemy to launch attacks against vessels in the Gulf of Oman and Strait of Hormuz, including vulnerable U.S. MCM [Mine countermeasures] forces.

Throughout a theater-entry operation, Air Force and Navy surveillance and strike aircraft, along with Army ATACMS [Army Tactical Missile System ] stationed in the UAE or Oman, if available, could help suppress Iran’s long-range ballistic missile and ASCM [Anti-ship cruise missile] threats, provide close air support to expeditionary forces, and prevent enemy ground forces from massing to execute counterattacks.

Seizing Islands at Strategic Locations.

In addition to creating lodgments on the Iranian coast, islands just inside the Gulf—including Abu-Musa, Sirri, Greater Tunb and Lesser Tunb—should be targeted by precision strikes and occupied by U.S. expeditionary forces as required. If permitted to remain under the command of the IRGCN [Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy], these islands could be staging locations for operations to re-seed minefields and harass U.S. forces and civilian shipping transiting the Strait.

Clearing the Path in to the Persian Gulf.

Completing mine clearing operations would likely be a key task for Littoral Combat Ships equipped with MCM modules, UUVs [Unmanned underwater vehicles], rotary wing aircraft, and supporting sensors. To prevent Iran from regenerating its maritime exclusion defenses, U.S. air forces would need to continue attacks against known mine storage and distribution sites, and destroy or suppress small craft, helicopters, submarines, and enemy “commercial” vessels capable of dispensing mines.

Although it is unknown to what extent Iran will expand its inventory of smart mines in the future, history has shown that even a small number of mines placed in shipping lanes “have been able to halt surface traffic when their presence was known.” Moreover, as mine countermeasure operations in 1991 and 2003 suggest, clearing large areas in the Strait of Hormuz and Persian Gulf of mines could require a month or even longer.

OK. So it’s not great literature. But fascinating reading.