A Navy F-35C takes off for its first night flight, a year ago this week, at Patuxent River Naval Air Station in Maryland.

Part 5 of 5

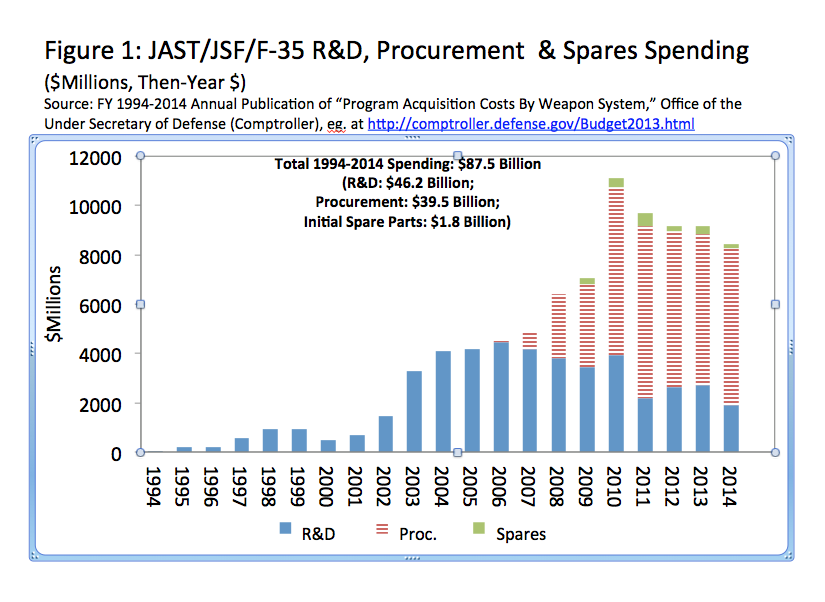

Each year the Defense Department’s comptroller, the Pentagon’s chief financial officer, publishes a report: Program Acquisition Costs by Weapon System.

The public and Congress have a right to expect these annual reports to be complete and accurate. These reports have identified spending amounts for research and development and for procurement, plus annual production authorizations, for the F-35, since the public origins of the program in 1994.

These reports show a total of $87.5 billion will have been spent on the F-35 program by the end of 2014: $46.2 billion for R&D; $39.5 billion for Procurement, and $1.8 billion for initial spare parts, as detailed in this chart from my third post in this series:

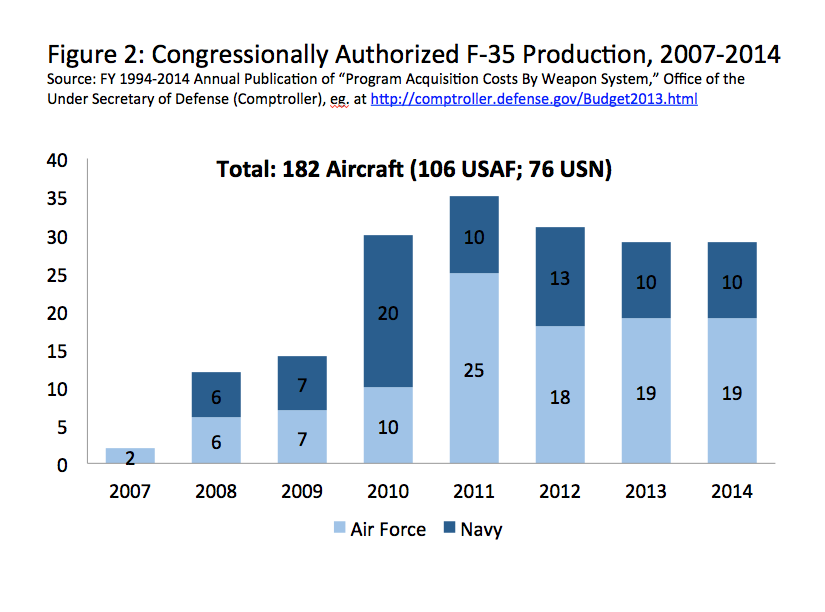

The reports also identify a total of 182 F-35 aircraft that will have been authorized for production by the end of fiscal year 2014, from this second chart in my third post:

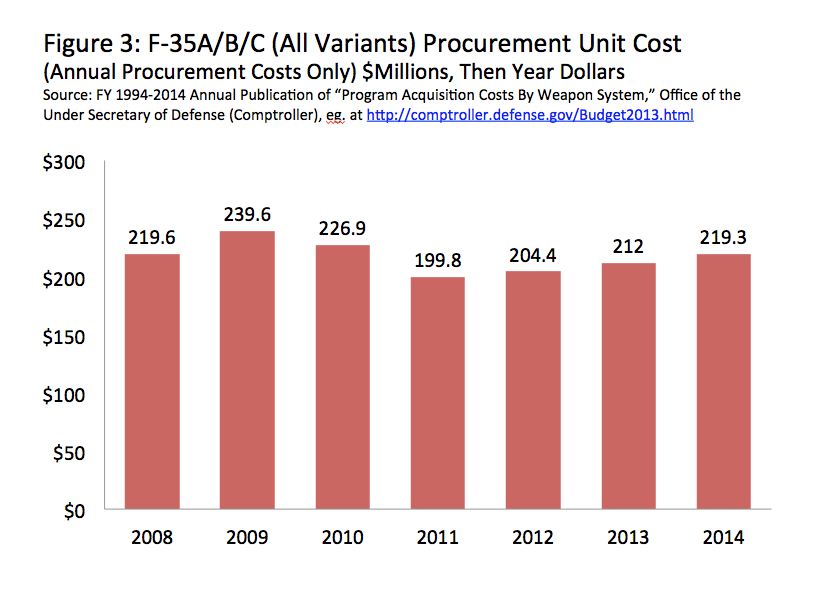

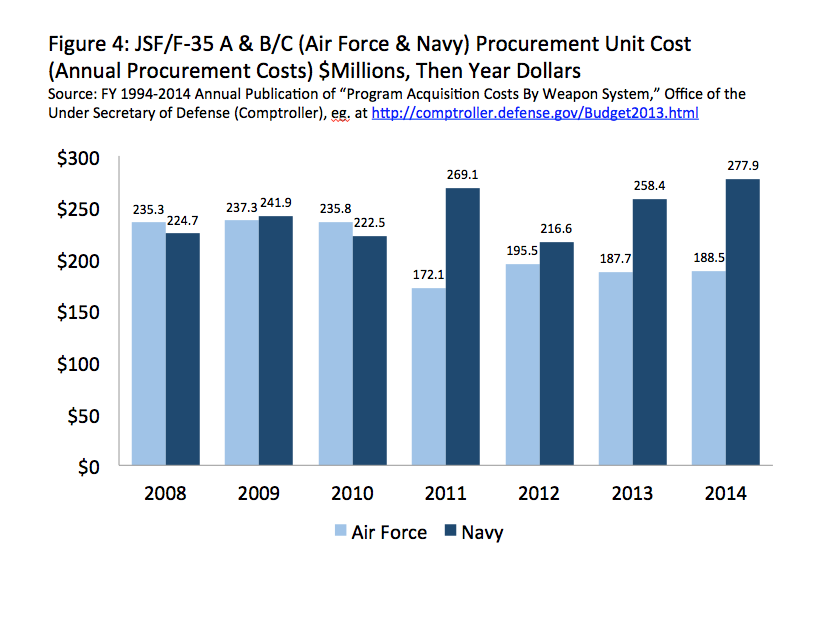

The breakdown of each year’s procurement spending and authorized production yields an annual F-35 unit production cost. For 2014, F-35As will cost $188.5 million each; F-35Bs and Cs will average $277.9 million each, and all F-35s will cost, on average, $219.3 million, as detailed in these two charts from posts three and four:

Claims by Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel and Air Force Lieut. General Christopher Bogdan, the F-35 program chief, that the F-35’s per-plane cost is “coming down” and “continues to come down,” respectively, are not accurate.

The Air Force’s F-35A will have been increasing in unit cost over the past two years; the Navy’s F-35B and C have been increasing in unit cost for the past three years, according to data from the Defense Department comptroller. (See Figure 4 above.) All F-35 variants, on average, have been increasing in unit cost since 2012 (or since 2011, if the comptroller’s data are right).

F-35 unit costs are going up, not down.

Having been in production for eight years, it is reasonable to characterize the F-35 production line as reasonably mature for whatever components have not already required modification.

We can expect additional costs on the production line to address problems yet to be discovered in the 60% of developmental testing and 100% of operational testing yet to occur—particularly in view of the fact that future tests will be tougher than past tests.

Unit costs are also likely to be impacted—upwards—by improvements and other modifications not yet a part of the F-35’s development. While some economies of scale may be achieved in larger production lots in the future, it is also reasonable to expect those economies to be offset, at a minimum, by additional disruptions and their resulting costs.

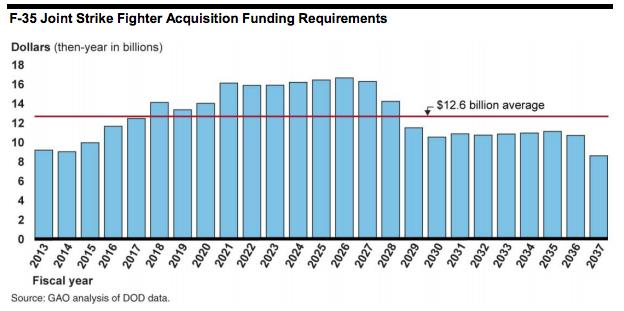

The huge procurement budgets slated for the F-35 in the future — as much as $16 billion in 2021 (an increase of almost $10 billion from the procurement budget for 2014) — call into question whether such sums will actually be available in an era of leaner military budgets.

Reductions in future F-35 procurement budgets to adjust to overall budget realities, combined with pressures from other Air Force and Navy requirements, make even more likely retrenchment—and still higher F-35 unit costs. All this makes it unlikely that the goal of buying 2,443 operational F-35s will be attained.

It is not unreasonable to expect the cost of future F-35s to be about where they are today, averaging more than $200 million per aircraft. It is also reasonable to doubt that F-35 unit costs—for a complete, operable F-35 force—will decline significantly, especially to a point anywhere close to the amounts currently projected for 2018 and beyond, pegged by Bogdan at $85 million.

The history of combat-aircraft acquisition warns us that F-35 unit costs will be much higher than are currently projected by the Pentagon and Lockheed-Martin, and will remain well above what can be characterized as affordable.

The data reported to the public and Congress on F-35 costs and production, from the Defense Department’s comptroller, do not conform to the data in other Pentagon reports. Even the number of F-35 units authorized to be produced, and the number to be delivered, are in dispute.

Without a complete and independent audit of the F-35 program, including any costs that may not now be a formal part of the program as reported in Selected Acquisition Reports, it is impossible to discern which F-35 cost reports, if any, are accurate, and precisely what F-35 costs are today and will be in the future.

The Defense Department’s SAR, and its seeming wishful declaration of the F-35’s total program costs coming down, should be audited by an independent and competent party. That GAO’s latest report on the F-35 has sided so clearly with the new hopefulness of program advocates for the F-35 calls into serious question whether GAO, or rather its current management, should be the party to such an accounting.

American taxpayers, the U.S. military services, and foreign purchasers — all of whom have been promised F-35 aircraft for as little as $85 million each — are in for a rude awakening. When real F-35 purchase prices unfold in the future, they may be as much as they are today—averaging more than $200 million per aircraft.

It remains inevitable that as actual costs sink in, fewer aircraft will be purchased.

This toxic stew of the F-35’s high cost, abetted by concurrent production, lagging performance and continuing design problems, has put U.S. and allied air power into a dive.

The dive will steepen so long as F-35 production at the currently-projected rates continues.

Part 1: The new era of F-35 good feelings

Part 2: Alphabet Soup: PAUCs, APUCs, URFs, Cost Variances and Other Pricing Dodges

Part 3: The deadly empirical data