Julian Wilson of Australia surfs the Trestles last fall.

The last time the Marines fought over a beach was in 1950, at Inchon, Korea. Their victory there turned the tide in the Korean war. Now they’re battling surfers for a piece of the southern California coast. This time, they fear a Marine defeat could hurt U.S. national security.

The surfers want a prime slice of beach just north of San Diego — and part of the Marines’ Camp Pendleton — officially listed by the National Register of Historic Places. The leathernecks fear that such a designation will tie them up in red tape, and complicate and delay their trademark amphibious training.

“A lot of us are surfers,” Marine Brigadier General Vincent Coglianese, commander at Camp Pendleton, tells Battleland (he boogie-boards, and is weighing a move up to a paddle board). “We just don’t want it historically listed.”

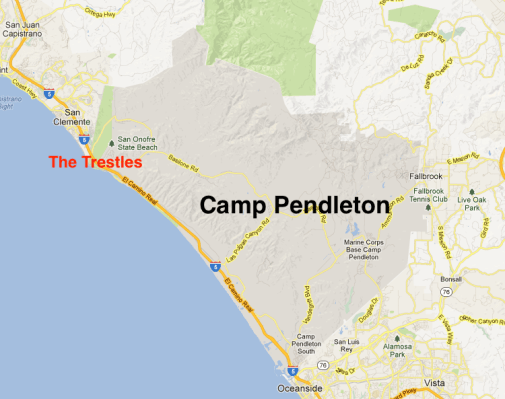

The Marines and surfers have existed peacefully, side by side, for decades at the Trestles beach, part of the 125,000-acre Camp Pendleton Marine base three miles south of San Clemente. That would supposedly continue if the National Register of Historic Places designates the beach as historic.

But the Marines’ job is to prepare for the worst case. They fear the designation will wound, perhaps critically, their training. “Right now the surfers coexist with us. They have everything they need as far as the surfing beach. We preserve that history. We’re proud of that,” Coglianese says. “We don’t understand the push to make this a historical site.”

But it is a pretty historic place.

President Nixon was out for a walk in 1969 when he added an extra mile to his stroll along the beach at San Clemente. He came across a beautiful stretch of oceanfront, officially closed to the public since the creation of Camp Pendleton in 1942.

That would be Trestles, a collection of surfing spots along San Onofre State Beach. Granting public access since 1971 to some of the world’s best surf since is a little-known Nixon legacy. This 3.5-mile (later extended to 5 miles) stretch of coastline, includes the 2.25-mile swath known as Trestles. It runs west along the Camp Pendleton border and Pacific Ocean and has since become one of the world’s great surfing meccas.

Nixon said he wanted to “provide an endowment of parklands and recreational areas…and make the beauties of the earth and sea more accessible.” He also wanted to help the local economy. It worked: the area is now home to three surfing magazines and several surfboard makers. The nearly 1 million annual visitors – many attracted by the local surf – bring in an estimated $10 million to local businesses.

Then-California governor Ronald Reagan strongly endorsed the opening of the beach. He saw it as a gift to future generations. “Unless we can preserve and protect the unspoiled areas which God has given us, we will have nothing to leave them,” the future President said. “As stewards of this land, we must use it judiciously and with a great sense of responsibility.”

The beach originally became a surfer’s haven in the 1930’s, and diehard surfers kept riding its waves even once the federal government closed it shortly after World War II began. They willingly risked citations, confiscation of their boards — and even bullets flying over their sun-streaked heads — to catch its epic waves.

The Navy-owned property — celebrated in the Beach Boys’ 1963 hit Surfin’ USA — is leased to the state of California, under a 50-year agreement due to end in 2021. For 42 years, the Marines have been, by all accounts, conscientious stewards of the coastline. They’ve limited their amphibious training to a small slice of the oceanfront because of a nearby nuclear power plant, an interstate highway, and assorted environmental restrictions.

Surf’s up for both Marines and surfers along Camp Pendleton’s roughly 20 miles of coastline.

The Surfrider Foundation, whose mission is “the protection and enjoyment of beaches, oceans and waves,” agrees the service has been good caretakers. But its members were spurred into nominating Trestles for a listing on the National Register of Historic Places following a controversial toll road proposal near the Trestles that was put on hold in 2008, although it continues to be debated. “The toll road fight brought attention to the historical significance of Trestles and San Onofre,” says Mark Rauscher, coastal preservation manager at Surfrider Foundation. “We saw the opportunity to get the first surfing area listed on the register and worked with the state to move it forward.”

Supporters say Trestles qualifies for the list because it is “virtually unparalleled in Southern California, due to high quality waves and the aesthetics of clean water and a still-natural environment.” Not only that: it also warrants inclusion “for its role in the establishment of surfing as a recreation, a lifestyle, a culture, and a part of the Southern California cultural identity.”

The Marines – surprise! — disagree.

They argue the beach doesn’t past muster as an historic site. Beyond that, the corps says designating the beach as historic would have serious and negative impacts on training and operations at Camp Pendleton.

“Trestles is not the sole example – or even the best example – of a property type important in illustrating the historic context of surfing in the United States,” Donald Schregardus, the Navy’s environmental chief, has told the California State Office of Historic Preservation.

20th Century Fox re-created the Guadalcanal landing for a film at Camp Pendleton in 1945, with 700 Marines, 62 landing boats, and six fighter planes playing roles, as did some real actors.

Even the surfers acknowledge that Camp Pendleton’s beaches have seen a lot of history. The local sands have “witnessed myriad units and amphibious craft and ships, including the Higgins boat being offloaded from Liberty ships, the Landing Ship Tank (LST) scuttling itself on Green Beach to disembark its supplies, and the Landing Vehicle Tracked (LVT) coming ashore with Marines to take their objective,” Surfrider’s application for the historic designation says.

Marines trained for Korea and Vietnam operations – which happened – and for amphibious operation during 1991’s Persian Gulf War against Iraq, which didn’t. There hasn’t been a major Marine amphibious assault since that Inchon landing 63 years ago.

Coglianese, Pendleton’s top officer, says jarheads and surfers have shared the beach without problems since the Vietnam war. The corps doesn’t want the complications that a historical listing might mean. “We’re concerned that would infringe on the No. 1 purpose of what we try to do,” he says, “which is to train young men and women to go into harm’s way.”

The Marines believe that designating a Trestles Historic District would lead to consultations and negotiations with surfers and their government allies that would inevitably complicate and delay needed training. They also see it as a kick in the teeth, given all that the corps has done to take care of the beach over the past 70 years. “We object to subjecting our activities, which have not been so regulated over the years, to regulation of an area that exists as it does today primarily due to our Marine Corps’ presence and mission,” says Stanley Norquist, a top Marine environmentalist at Pendleton.

The Marines also argue that a decision to give the beach historical status could hurt national security. “Recently the President has reemphasized our strategy toward the Pacific,” Coglianese says. “The beaches are critical. The reason we’re on the ocean is because of amphibious training. It concerns me greatly when people, meaning well, are trying to move forward to possibly encroach or limit our training.”

Proponents say the listing won’t change anything. Surfriders’ petition for the historic designation, they note, contains an escape hatch that allows the Marines to seek Trestles’ removal from the list if the corps’ “military training exercises and/or operations are adversely affected.”

The Marines believe such assurances are as skimpy as a pair of Speedos. Coglianese declares them “unenforceable” and dangerous to the corps’ role in defending the nation. “This mission cannot be compromised or otherwise subordinated to another land use – as would be the case if the THD is listed or found eligible for listing,” he wrote the California State Office of Preservation last winter.

The Marines have always fared well on real battlefields, as well as on the political ones back in Washington, D.C. But they’re facing a struggle in the Golden State.

The tides of history may be shifting against them. In February, California’s Historical Resources Commission dismissed the Marines’ concerns when it voted unanimously to approve the listing. A final decision from the National Register of Historic Places could come at any time.