When I heard Leon Panetta’s announcement about lifting the combat restrictions on women in the military, I immediately thought of former Army National Guard Sergeant Paigh Bumgarner.

Bumgarner had deployed to Iraq, where she had served as a convoy gunner in a unit that came under fire.

“Once we got through,” Bumgarner recalls, “they tried to hit us with a VBED [vehicle-borne explosive device], but I ordered ‘No one gets close to this convoy, so it was taken out, a confirmed kill.”

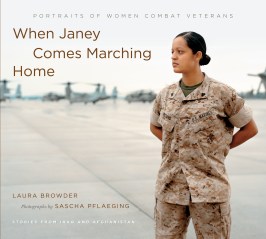

Bumgarner told me, in a interview for my book, When Janey Comes Marching Home: Portraits of Women Combat Veterans, that she put the remains of her best friend in a body bag. She got the medics to bandage up the soldiers who had sustained shrapnel damage.

As she recalls, “I remember during the craziness of everything, the first sergeant [we were escorting] came up and tried to take over, and I was like, ‘I’m in control of this convoy….After that, all the guys were like, ‘I’ll go anywhere with you. I’ll follow you anywhere.’”

As the nation’s experts debate what the new ruling means, and whether women are in fact capable of serving on equal terms with men, we would all do well to listen to some real experts: female combat veterans.

As I talked to more than 50 women who have deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan—or both—I was struck by how determined many of these women were to serve their country on the battlefield. Army Staff Sergeant Jamie Rogers told me, “As a soldier, it’s something that you always want to do. For myself, I felt it was my obligation and that’s what I had been training for all these years, to do my job in combat. And I was very honored. I got to lead soldiers in combat, and I proved to myself that all this training was worthwhile.”

Rogers, who was in the military police, was out on patrol 12 hours of every 24. As she said of the experience, “It’s very life-changing.” While civilians may still see women in the military as being marginal, no female soldier I ever talked to saw herself as anything less than a military professional on par with her male comrades in arms.

As one West Point graduate explained to me, it felt as though she had been reading technical manuals on how to ride a bicycle—but to really be a soldier, she had to get on the bike itself. I heard variations of this sentiment from many women. And of course, many of the women I talked to did serve as explosives-sniffing dog handlers, military police whose jobs involved busting down doors and conducting house-to-house searches, and convoy gunners like Bumgarner.

Yet while they, and everyone they worked with and for, knew that they were in combat, they were still being denied full credit for their service on the front lines.

The grit they exhibited was extraordinary: Army Captain Kelly Nocks, for instance, was leading a convoy in 2003 when her unarmored Humvee ran over an IED, blowing up her leg. She had to undergo 18 surgeries and was in danger of losing her leg.

Yet Captain Nocks fought as hard as she could to regain her strength so she could pass the physical fitness test. When I talked to her in 2007, she was considered deployment-ready, although she was not allowed to bear weight, crawl, or run. As she told me, “I know I’m going back. I will deploy. I still think that I’m doing great things, that I can continue in my job and stay in the Army.”

When I hear people question the physical strength and stamina of female troops, I only wish I could introduce them to Kelly Nocks.

As the nation debates what it will mean for women to participate in combat, it is easy to lose sight of some basic truths: that in our two most recent wars, over 280,000 women have served in combat zones in which there is very little distinction between front lines and rear support, and they have served with distinction.

As Army Sergeant First Class Gwendolyn-Lorene Lawrence, who served in Bosnia in 1996, said, “The military was an opportunity. The Army, Air Force, Navy, Marines—all the branches would say, ‘Okay, women, prove your point. Prove you’re citizens.’ We shot that. We went over and beyond to say, ‘Here we are. We are citizens. We deserve the right to defend our country in whatever capacity we can.’”

As recently as 1982, the Equal Rights Amendment came within a hair’s breadth of passing—and then failed because opponents raised the specter of women in combat. With Defense Secretary Panetta’s announcement, we have come a giant step closer for American women to become full citizens in every sense of the word.

Laura Browder is a professor of American Studies at the University of Richmond. Her most recent book is When Janey Comes Marching Home: Portraits of Women Combat Veterans, with photographs by Sascha Pflaeging.