Air Force MQ-1 Predator drone operators at work.

A new Pentagon study contrasting the mental-health concerns of pilots who actually climb into the cockpit – as opposed to military drone drivers who sit at desks – shows that land-based pilots suffer 60% more mental-health maladies than their flying counterparts.

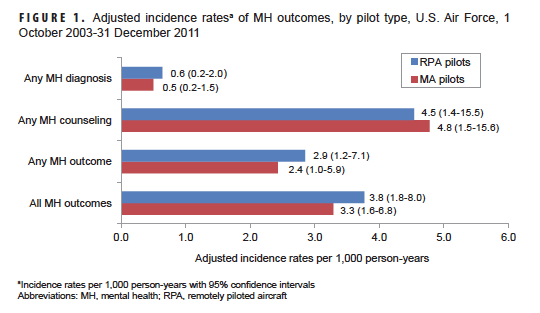

But after adjusting the data for age, number of deployments, time in service, and prior mental-health problems, “there was no significant difference in the rates of mental health diagnoses, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depressive disorders, and anxiety disorders between remotely piloted aircraft and manned aircraft pilots,” the study said.

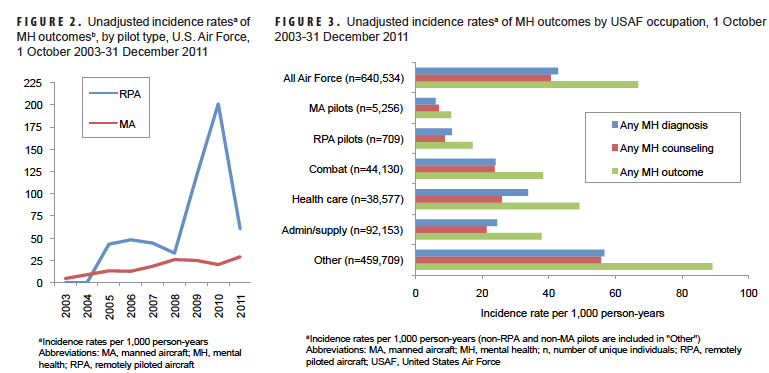

The report, in the March issue of the Medical Surveillance Monthly Report said it “is the first to document the frequencies, incidence rates, and trends of mental health outcomes among remotely-piloted aircraft pilots within the active component of the USAF, and how these rates compare to those among manned aircraft pilots (fixed wing and rotary wing) and among airmen in other USAF occupations during the same time period.”

Drone operators tend to work at stateside bases, and return to their homes at the end of their shifts, unlike most manned-aircraft pilots, who are forward deployed into war zones. Relations between the two communities aren’t always smooth: in one of his final acts as defense secretary, Leon Panetta sparked a firestorm among military traditionalists when he created the Distinguished Warfare Medal, to be awarded to drone operators and others who perform extraordinary acts without endangering themselves in combat. New Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel has ordered a review of the medal and its ranking above the Bronze Star and Purple Heart.

The study, by Pentagon medical researchers Jean Otto and Bryant Webber, listed the pressures faced by drone pilots:

Along with witnessing traumatic experiences, such as those associated with PTSD in traditional combat, remotely-piloted aircraft crew members may face several additional challenges, some of which may be unique to telewarfare: lack of deployment rhythm and of combat compartmentalization (i.e., a clear demarcation between combat and personal/family life); fatigue and sleep disturbances secondary to shift work; austere geographic locations of military installations supporting remotely-piloted aircraft missions; social isolation during work, which could diminish unit cohesion and thereby increase susceptibility to PTSD; and sedentary behavior with prolonged screen time, implicated as psychological challenges in the adult video gaming community.

Not sure how much sympathy that roster is going to win among pilots prepping for combat missions in war zones.

The study found:

— “Approximately 8.2 percent of remotely-piloted aircraft pilots and 6.0 percent of manned aircraft pilots had at least one mental-health outcome” including adjustment disorder, alcohol abuse, anxiety disorder and depression.

— “The incidence rates of all mental-health outcomes among remotely-piloted aircraft pilots was 25.0 per 1,000 person-years and among manned aircraft pilots was 15.9 per 1,000 person-years.”

— “Between October 2003 and December 2011, approximately one of every 12 remotely-piloted aircraft pilots and one of every 17 manned aircraft pilots received at least one incident mental-health outcome (i.e., first diagnosis of the outcome during their military careers).”

While the raw data suggested that drone pilots suffer greater mental-health issues than manned pilots, the study’s authors decided to call it a draw: “In summary, the findings of this report suggest that remote combat does not increase the risk of mental-health outcomes beyond that seen in traditional combat,” the report concluded. “Military policymakers and clinicians should recognize that remotely-piloted aircraft pilots have a similar mental health risk profile as manned aircraft pilots.”