On Sept. 17, the Pakistani government shut down access to YouTube. The purported reason was to block the anti-Muslim film trailer that was inciting protests around the world.

One little-noticed consequence of this decision was that 215 people in Pakistan suddenly lost their seats in a massive, open online physics course. The free college-level class, created by a Silicon Valley start-up called Udacity, included hundreds of short YouTube videos embedded on its website. Some 23,000 students worldwide had enrolled, including Khadijah Niazi, a pigtailed 11-year-old in Lahore. She was on question six of the final exam when she encountered a curt message saying “this site is unavailable.”

(GOOGLE+ HANGOUT: Can Online Mega Courses Change Education?)

Niazi was devastated. She’d worked hard to master this physics class before her 12th birthday, just one week away. Now what? Niazi posted a lament on the class discussion board: “I am very angry, but I will not quit.”

In every country, education changes so slowly that it can be hard to detect progress. But what happened next was truly different. Within an hour, Maziar Kosarifar, a young man taking the class in Malaysia, began posting detailed descriptions for Niazi of the test questions in each video. Rosa Brigída, a novice physics professor taking the class from Portugal, tried to create a workaround so Niazi could bypass YouTube; it didn’t work. From England, William, 12, promised to help and warned Niazi not to write anything too negative about her government online.

None of these students had met one another in person. The class directory included people from 125 countries. But after weeks in the class, helping one another with Newton’s laws, friction and simple harmonic motion, they’d started to feel as if they shared the same carrel in the library. Together, they’d found a passageway into a rigorous, free, college-level class, and they weren’t about to let anyone lock it up.

By late that night, the Portuguese professor had successfully downloaded all the videos and then uploaded them to an uncensored photo-sharing site. It took her four hours, but it worked. The next day, Niazi passed the final exam with the highest distinction. “Yayyyyyyy,” she wrote in a new post. (Actually, she used 43 y’s, but you get the idea.) She was the youngest girl ever to complete Udacity’s Physics 100 class, a challenging course for the average college freshman.

That same day, Niazi signed up for Computer Science 101 along with her twin brother Muhammad. In England, William began downloading the videos for them.

High-End Learning on the Cheap

The hype about online learning is older than Niazi. In the late 1990s, Cisco CEO John Chambers predicted that “education over the Internet is going to be so big, it is going to make e-mail usage look like a rounding error.” There was just one problem: online classes were not, generally speaking, very good. To this day, most are dry, uninspired affairs, consisting of a patchwork of online readings, written Q&As and low-budget lecture videos. Many students nevertheless pay hundreds of dollars for these classes — 3 in 10 college students report taking at least one online course, up from 1 in 10 in 2003 — but afterward, most are no better off than they would have been at their local community college.

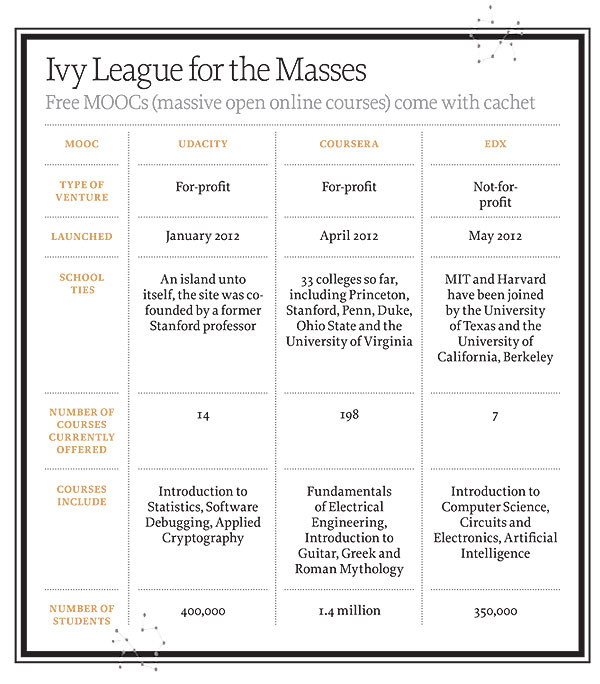

Now, several forces have aligned to revive the hope that the Internet (or rather, humans using the Internet from Lahore to Palo Alto, Calif.) may finally disrupt higher education — not by simply replacing the distribution method but by reinventing the actual product. New technology, from cloud computing to social media, has dramatically lowered the costs and increased the odds of creating a decent online education platform. In the past year alone, start-ups like Udacity, Coursera and edX — each with an elite-university imprimatur — have put 219 college-level courses online, free of charge. Many traditional colleges are offering classes and even entire degree programs online. Demand for new skills has reached an all-time high. People on every continent have realized that to thrive in the modern economy, they need to be able to think, reason, code and calculate at higher levels than before.

At the same time, the country that led the world in higher education is now leading its youngest generation into a deep hole. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Americans owe some $914 billion in student loans; other estimates say the total tops $1 trillion. That’s more than the nation’s entire credit-card debt. On average, a college degree still pays for itself (and then some) over the course of a career. But about 40% of students at four-year colleges do not manage to get that degree within six years. Regardless, student loans have to be repaid; unlike other kinds of debt, they generally cannot be shed in bankruptcy. The government can withhold tax refunds and garnish paychecks until it gets its money back — stifling young people’s options and their spending power.

For all that debt, Americans are increasingly unsure about what they are getting. Three semesters of college education have a “barely noticeable” impact on critical thinking, complex reasoning and writing skills, according to research published in the 2011 book Academically Adrift. In a new poll sponsored by TIME and the Carnegie Corporation of New York, 80% of the 1,000 U.S. adults surveyed said that at many colleges, the education students receive is not worth what they pay for it. And 41% of the 540 college presidents and senior administrators surveyed agreed with them.

(MORE: TIME/Carnegie’s Higher Education Poll)

Arriving at this perilous intersection of high demand, uneven supply and absurd prices are massive open online courses (endowed with the unfortunate acronym MOOCs), which became respectable this year thanks to investments from big-name brands like Harvard, Stanford and MIT. Venture capitalists have taken a keen interest too, and the business model is hard to resist: the physics class Niazi was taking cost only about $2 per student to produce.

Already, the hyperventilating has outpaced reality; desperate parents are praying that free online universities will finally pop the tuition bubble — and nervous college officials don’t want to miss out on a potential gold rush. The signs of change are everywhere, and so are the signs of panic. This spring, Harvard and MIT put $60 million into a nonprofit MOOC (rhymes with duke) venture called edX. A month later, the president of the University of Virginia abruptly stepped down — and was then quickly reinstated — after an anxious board member read about other universities’ MOOCs in the Wall Street Journal.

One way or another, it seems likely that more people will eventually learn more for less money. Finally. The next question might be, Which people

How the Brain Learns

This fall, to glimpse the future of higher education, I visited classes in brick-and-mortar colleges and enrolled in half a dozen MOOCs. I dropped most of the latter because they were not very good. Or rather, they would have been fine in person, nestled in a 19th century hall at Princeton University, but online, they could not compete with the other distractions on my computer.

I stuck with the one class that held my attention, the physics class offered by Udacity. I don’t particularly like physics, which is why I’d managed to avoid studying it for the previous 38 years. What surprised me was the way the class was taught. It was designed according to how the brain actually learns. In other words, it had almost nothing in common with most classes I’d taken before.

Minute 1: Physics 100 began with a whirling video montage of Italy, slow-motion fountains and boys playing soccer on the beach. It felt a little odd, like Rick Steves’ Physics, but it was a huge improvement over many other online classes I sampled, which started with a poorly lit professor staring creepily into a camera.

When the Udacity professor appeared, he looked as if he were about 12; in fact, he was all of 25. “I’m Andy Brown, the instructor for this course, and here we are, on location in Siracusa, Italy!” He had a crew cut and an undergraduate degree from MIT; he did not have a Ph.D. or tenure, which would turn out to be to his advantage.

“This course is really designed for anyone … In Unit 1, we’re going to begin with a question that fascinated the Greeks: How big is our planet?” To answer this question, Brown had gone to the birthplace of Archimedes, a mathematician who had tried to answer the same question over 2,000 years ago.

Minute 4: Professor Brown asked me a question. “What did the Greeks know?” The video stopped, patiently waiting for me to choose one of the answers, a task that actually required some thought. This happened every three minutes or so, making it difficult for me to check my e-mail or otherwise disengage — even for a minute.

“You got it right!” The satisfaction of correctly answering these questions was surprising. (One MOOC student I met called it “gold-star methadone.”) The questions weren’t easy, either. I got many of them wrong, but I was allowed to keep trying until I got the gold-star fix.

(GRAPHIC: Degrees of Difficulty)

Humans like immediate feedback, which is one reason we like games. Researchers know a lot about how the brain learns, and it’s shocking how rarely that knowledge influences our education system. Studies of physics classes in particular have shown that after completing a traditional class, students can recite Newton’s laws and maybe even do some calculations, but they cannot apply the laws to problems they haven’t seen before. They’ve memorized the information, but they haven’t learned it — much to their teachers’ surprise.

In a study published in the journal Science in 2011, a group of researchers conducted an experiment on a large undergraduate physics class at the University of British Columbia. For a week, one section of the class received its normal lecture from a veteran, highly rated professor; another section was taught by inexperienced graduate students using strategies developed from research into human cognition. Those strategies mirrored those in Udacity’s class. The students worked in small groups to solve problems with occasional guidance from the instructor. They got frequent feedback. In the experimental group with novice instructors, attendance increased 20% and students did twice as well on an end-of-week test.

Minute 8: Professor Brown explained that Plato had also tried (and failed) to estimate the earth’s circumference. Brown did this by jotting notes on a simple white screen. Like all the other videos in the course, this clip lasted only a few minutes. This too reflects how the brain learns. Studies of college students have shown that they can focus for only 10 to 18 minutes before their minds begin to drift; that’s when their brains need to do something with new information — make a connection or use it to solve a problem.

At this point in the Udacity class, three video clips into the experience, about 15,000 students were still paying attention, according to the company’s metrics. But that’s actually high for a MOOC. (Since it requires little effort and no cost to enroll, lots of people dip in and out of these classes out of curiosity. Only 1 in 10 of those enrolled in a Udacity class typically makes it all the way to a course’s last video.) Like most other online classes, it was asynchronous, so I could rewind or leave and come back whenever I wanted. This also accords with how the brain works: humans like autonomy. If they learn best late at night, they like to learn at night, on their own terms.

Minute 57: After 47 fast-paced videos spliced with pop quizzes, I did actually know how big the earth was. Brown had reviewed geometry and trigonometry with examples from actual life. And when it came time to put it all together, I got to see him measure a shadow that formed a right triangle, setting up a mathematical proportion to calculate the circumference of the earth, just like an ancient mathematician.

“Congratulations!” he said. “This is really incredible, what you can do now.” Then he asked the class to send in videos of themselves measuring shadows. I was skeptical. Would people actually do this?

Yes, they would. The first video was from a young woman in Tampere, Finland — a drummer who wanted to change her career. There she was, with yellow dreadlocks, measuring a shadow in a parking lot. Another woman submitted photos of herself completing the experiment in Texas, plus a poem. A poem! “We solve for C, and long at last/ stalk a route into our own past.”

The Finn cheered. “Super artistic!” Brown showed the poem around the Udacity office. One student did the experiment at 0 degrees latitude in Ecuador. Many more people posted questions; within minutes, they got detailed, helpful answers from other students. It was as if a whole pop-up learning community had materialized overnight, and it was strangely alive.

Turning Down Professors

When he was a tenured professor at Stanford, Sebastian Thrun, the CEO and co-founder of Udacity, did not teach according to how the brain learns. He is not proud of this fact. “I followed established wisdom,” he says. His students, who were used to traditional lectures, gave him high marks on his course evaluations. They didn’t know what they were missing.

In 2011 Thrun and fellow professor Peter Norvig decided to put their Artificial Intelligence class online. But when they sampled other online courses, they realized that most of them were mediocre. To captivate students from afar, they would need to do something different. So they started planning lessons that would put the student at the center of everything. They created a series of problems for students to solve so that they had to learn by doing, not by listening.

By last fall, 160,000 people had enrolled. But the class was not particularly inspiring — at first. One student complained that the software allowed students to try each problem only once. “I realized, ‘Wow, I’m setting students up for failure in my obsession to grade them,’ ” says Thrun. So he changed the software to let students try and try until they got it right. He also paid attention to the data, and he had a lot of it. When tens of thousands of students all got the same quiz problem wrong, he realized that the question was not clear, and he changed it. And the students themselves transformed other parts of the class, building online playgrounds to practice what they were learning and even translating the class into 44 languages.

Meanwhile, Thrun had told his Stanford students they could take the class online if they didn’t want to attend lectures. More than three-quarters of them did so, viewing the videos from their dorms and participating as if they were thousands of miles away. Then something remarkable happened. On the midterm, the Stanford students scored a full letter grade higher on average than students had in previous years. They seemed to be learning more when they learned online. The same bump happened after they took the final.

(MORE: Reinventing College)

Still, the Stanford students were not the stars of the class. At the end of the semester, not one of the course’s 400 top performers had a Stanford address.

The experience forced Thrun to rethink everything he knew about teaching, and he built Udacity upon this reordering of the universe. Unlike Coursera, another for-profit MOOC provider — which has partnered with dozens of schools, including Stanford, Princeton and, more recently, the University of Virginia — Udacity selects, trains and films the professors who teach its courses. Since it launched in January, Udacity has turned down about 500 professors who have volunteered to teach, and it has canceled one course (a math class that had already enrolled 20,000 students) because of subpar quality.

Right now, most MOOC providers do not make a profit. That can’t continue forever. Udacity will probably charge for its classes one day, Thrun says, but he claims the price will stay very low; if not, he predicts, a competitor will come along and steal away his students.

Udacity does not offer a degree, since it’s not an accredited university. Students get a ceremonial certificate in the form of a PDF. Grades are based on the final exam. Students who choose to take the final for Udacity’s computer-science course at an independent testing center (for $89) can get transfer credits from Colorado State University–Global Campus, an online-only school.

Getting more colleges to accept transfer credits would be nice, but in the longer term, Udacity aims to cut out the middleman and go straight to employers. This week, Udacity announced that six companies, including Google and Microsoft, are sponsoring classes in skills that are in short supply, from programming 3-D graphics to building apps for Android phones.

Meanwhile, about 3,000 students have signed up for Udacity’s employer-connection program, allowing their CVs to be shared with 350 companies. Employers pay Udacity a fee for any hires made through this service. So far, about 20 students have found work partly through Udacity’s help, Thrun says. Tamir Duberstein, 24, who studied mechanical engineering in Ontario, recently got two job offers after completing six Udacity courses. He took one of the offers and now works at a software company in San Francisco.

Still, it will be a long time before companies besides high-tech start-ups trust anything other than a traditional degree. That’s why hundreds of thousands of people a year enroll in the University of Phoenix, which most students attend online. Says University of Phoenix spokesman Ryan Rauzon: “They need a degree, and that isn’t going to change anytime soon.”

MOOCs vs. the College Campus

To compare my online experience with a traditional class, I dropped into a physics course at Georgetown University, the opposite of a MOOC. Georgetown admitted only 17% of applicants last fall and, with annual tuition of $42,360, charges the equivalent of about $4,200 per class.

The university’s large lecture course for introductory physics accommodates 150 to 200 students, who receive a relatively traditional classroom experience — which is to say, one not designed according to how the brain learns. The professor, who is new to the course, declined to let me visit.

But Georgetown did allow me to observe Physics 151, an introductory class for science majors, and I soon understood why. This class was impressively nontraditional. Three times a week, the professor delivered a lecture, but she paused every 15 minutes to ask a question, which her 34 students contemplated, discussed and then answered using handheld clickers that let her assess their understanding. There was a weekly lab — an important component missing from the Udacity class. The students also met once a week with a teaching assistant who gave them problems designed to trip them up and had them work in small groups to grapple with the concepts.

The class felt like a luxury car: exquisitely wrought and expensive. Fittingly, it met in a brand-new, state-of-the-art $100 million science center that included 12 teaching labs, six student lounges and a café. It was like going to a science spa.

Elite universities like Georgetown are unlikely to go away in the near future, as even Udacity’s co-founder (and Stanford alum) David Stavens concedes. “I think the top 50 schools are probably safe,” he says. “There’s a magic that goes on inside a university campus that, if you can afford to live inside that bubble, is wonderful.”

Where does that leave the rest of the country’s 4,400 degree-granting colleges? After all, only a fifth of freshmen actually live on a residential campus. Nearly half attend community colleges. Many never experience dorm life, let alone science spas. To return to reality, I visited the University of the District of Columbia (UDC) — a school that, like many other colleges, is not ranked by U.S. News & World Report.

When I arrived at the UDC life-sciences building, I met Professor Daryao Khatri, who has been teaching for 37 years and yet seemed genuinely excited to get to his first day of class in a new semester.

“They hate physics,” he said about his students, smiling. “You will see. They are terrified.” He led me to his classroom, a lab with fluorescent lights and a dull yellow linoleum floor. His 20 students were mostly young adults with day jobs, which is why they were going to school at night. Many hoped to go to medical school one day, and they needed to take physics to get there.

Khatri started the class by asking the students to introduce themselves. “I took physics in high school,” said one woman, a biology major, “and it was the hardest class I ever had.”

“I’m about to change that!” Khatri shouted. Another young woman said, “I took calculus online, and it was just awful.” It felt more like a support group than a college course. Then Khatri detailed his rules for the class. “Please turn the cell phones off,” he said in a friendly voice. “Not on vibrate. I will know. I will take it away. Cell phones are a big disaster for the science classes.”

Khatri had less than one-half of 1% of the students that Professor Brown had on Udacity, but he was helping them with many skills beyond physics. He was cultivating discipline and focus, rebuilding confidence and nurturing motivation. “Please complain if you aren’t learning,” he said more than once.

After a full hour of introductions and expectations, Khatri started reviewing geometry and trigonometry so that the students would have enough basic math to begin. He did this in far more detail than Brown had on Udacity, and it was clear from their questions that many of the students needed this help. As with most other Americans, their math and science background was spotty, with big holes in important places. For the next hour, Khatri called on every student to answer questions and solve problems; just as on Udacity, they couldn’t zone out for long.

Three weeks later, I returned to Khatri’s class. He was about a week behind the Udacity pace, and his quizzes were easier. But not a single student had dropped his class. And when I asked a group of students if they would ever take this class online, they answered in unison: “No way.”

At this stage, most MOOCs work well for students who are self-motivated and already fairly well educated. Worldwide, the poorest students still don’t have the background (or the Internet bandwidth) to participate in a major way. Thrun and his MOOC competitors may be setting out to democratize education, but it isn’t going to happen tomorrow.

What is going to happen tomorrow? It seems likely that very selective — and very unselective — colleges will continue to thrive. At their best (and I was only allowed to witness their best, it’s worth noting), Georgetown and UDC serve a purpose in a way that cannot easily be replicated online. The colleges in the middle, though — especially the for-profit ones that are expensive but not particularly prestigious — will need to work harder to justify their costs.

Ideally, Udacity and other MOOC providers will help strip away all the distractions of higher education — the brand, the price and the facilities — and remind all of us that education is about learning. In addition to putting downward pressure on student costs, it would be nice if MOOCs put upward pressure on teaching quality.

By mid-October, YouTube remained dark in Pakistan, and the power blinked out for about four hours a day at Niazi’s home in Lahore. But she had made it halfway through Computer Science 101 anyway, with help from her classmates.

Niazi loved MOOCs more than her own school, and she wished she could spend all day learning from Andy Brown. But when I asked her if she would get her degree from Udacity University, if such a thing were possible, she demurred. She had a dream, and it was made of bricks. “I would still want to go to Oxford or Stanford,” she said. “I would love to really meet my teachers in person and learn with the whole class and make friends—instead of being there in spirit.”

Ripley, a TIME contributing writer, is an Emerson Fellow at the New America Foundation, where she is writing a book about education around the world