Reuters

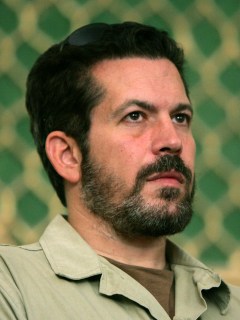

TOKYO – Wars can attract some odd, fringe characters, but I never met anyone stranger or more out on the fringe than Jonathan Keith Idema, who died recently in Mexico of complications from AIDS.

A career con artist and military wannabe, Idema showed up early during the war in Afghanistan. He posed variously as a government operative, military spokesman, freelance terrorist hunter, adviser to the Afghan government and all-around American patriot. He conned journalists, NATO commanders and Afghan militia leaders, wrote a book in which he was the hero of desperate shootouts that never took place, and pitched movie and documentary deals about exploits that never happened. He was finally thrown into an Afghan prison in 2004 for kidnapping and torturing Afghan civilians.

I knew Idema and I was amazed he lasted as long as he did.

I first met him in the early 1990s and found him an entertaining but not convincing liar. He boasted, for example, that he had been in the Special Forces and had been on covert missions all over the world. It was baloney, of course; the last person a real SF soldier would talk to about things like that is a news reporter.

When Idema was convicted of fraud in North Carolina in the mid-90s, court records showed that he served just one hitch in the Army, and that the closest he ever came to the SF was packing parachutes in a support unit. One of his commanders called him “the most unmotivated, unprofessional, immature enlisted man I have ever known.”

I saw Idema several times over the years and what I remember most is that he never seemed to know where his own fantasies ended and the real world started. I’ll give you an example.

I was with a group of journalists, aid workers and others who had chartered a plane to fly from Tajikistan to Kabul after the Taliban evacuated in late 2001. The plane blew a tire on takeoff from the Dushanbe airport and it was not replaced until late in the day. It was agreed that rather than risk flying over the 20,000-foot Hindu Kush at night, in midwinter, with a dodgy pilot and a plane with no instruments, we should wait until the next day.

But among the passengers was a group of displaced Afghans frantic to get home, who angrily demanded that we take off right away. Idema, who was also a passenger and was dressed in his customary paramilitary gear and dark sunglasses, poured fuel on the fire by shouting that he knew the “codes” at the Bagram airfield. He said that once we were over the runway, he could radio down to the control tower to get American troops to “turn on the lights.”

This was pure fantasy, of course. There were no “codes”; there was no way to communicate with American troops from a broken-down, Russian-built cargo plane; and American ground controllers certainly would not “turn on the lights” for an unidentified plane that just happened to show up in the middle of a war zone. If that plane took off that afternoon, everybody aboard was going to die, including Idema.

It wasn’t until a several of us dragged Idema aside and impressed upon him the seriousness of the situation, that he finally conceded that maybe he didn’t really know any “codes” or radio frequencies after all. We called the flight off, and everyone lived for another day. As did Idema’s flights of fantasy.