A long-after-action report

There’s a profound sense of deja vu among those of us who came of age — in uniform, at school, in politics — during the Vietnam war. So much of what is happening today resonates with that conflict in ways both good and ill.

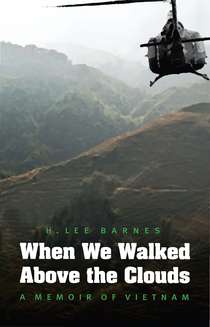

Lee Barnes has just written When We Walked Above the Clouds about his experiences early in the southeast Asian campaign as a Green Beret. He spoke with Battleland about that time nearly a half-century ago in an email exchange, and what relevance it has to today.

What is the most important thing you learned in writing When We Walked Above the Clouds?

I can’t think of just one thing to answer with. There’s no one learning experience in putting together a war memoir. One important result of my having written When We Walked Above the Clouds was the way it served to reconnect with and build friendships among my former teammates as we rehashed the events that shaped us. We discovered in picking away at details that decades later the people we met over the years can’t and don’t understand us the way we understand one another.

Another thing that eventuated from writing it was that I realized why over the years my developing, much less nurturing, relationships had been difficult and why I had deep mistrust of authority. The reason revealed itself soon after I completed the first draft of the memoir. I was driving along in traffic, everything normal, when I suffered a panic attack, an event that spurred me to seek help at the VA where I was quickly diagnosed as having delayed-onset PTSD. For four years now I’ve been working with the VA to develop coping skills.

What are the key lessons you learned in Vietnam as a Green Beret?

All these years later, after earning a graduate degree, publishing books, earning a black belt, and winning tennis tournaments, the one trophy I most prize remains my green beret. As my teammate Rich Norwood said, “We had the adventure of our lives.” I wouldn’t trade a moment of my tour in ’Nam for any safe stateside experience. I learned I could face danger and endure deprivation and go for days with minimum rest to accomplish a mission, and I was willing to repeat the cycle of risk and hardship again and again.

I learned that complaining is an excuse for not knowing how to live with what life deals you. I learned the value of humility and that heroism, in order to be recognized, requires both a substantial act and witnesses to verify it, but courage is the simple act of pulling on a backpack, picking up a rifle, and taking a walk into the unknown. Doing so won’t make a man a hero, but it helps to make him a better man. I guess that’s why I feel as I do about the teammates that convinced me to write When We Walked Above the Clouds. It’s really the story of good men made better because they never shirked their duty or hesitated to load up their weapon and take a walk, and they did so without ever claiming to be heroes.

Did you ever sour on the Vietnam conflict? If so, when and why?

Questions about policy and strategy, of course, are not questions soldiers on the ground ask then or now. Those committed to the battle concern themselves with each mission, and aside from survival, their worries are how to best to safeguard their buddies and accomplish the immediate operation. In part, my memoir, as will any war memoir of worth, deals with these two vital issues.

I don’t recall ever questioning why we were in ’Nam, not at the time I was there. I was a member of a very special unit and those of us honored to wear the Green Beret weren’t the type to doubt our leaders or question our orders (although at one stage I did). The mission and the men who went with us were everything.

The large questions troubled me much later as it became apparent by 1973 that we would lose the peace no matter how many engagements we won on the battlefield and the realization struck me that my teammates and tens of thousands of my generation had died in a futile cause. Of course, one can argue that Vietnam was in essence a proxy war that helped bankrupt the Soviets, and if that’s the case, it served some cause in breaking apart the Soviet empire.

H. Lee Barnes

Do you think your book is relevant to today’s fighting in Afghanistan? If so, how?

As much as anything else, writing my memoir confirmed for me that Faulkner was right in saying that “The past isn’t history. It’s not even past.” I don’t mean this just in the personal sense, but in the sense that Vietnam is alive in the conscience of America in ways that no other war, except for perhaps the Civil War, is. No other war has had the impact on decisions that guide America’s foreign and military policies. The abiding question that administration after administration has had to address when employing military intervention inevitably is “Will this be another Vietnam?” This is now how questions about Afghanistan are framed, especially those that deal with the issue of victory or winning. Is it winnable? What will be the cost?, etc.

Similarities, at least in the political sense, between my generation’s war and this generation’s war are striking. The individual acts and bravery of the Iraq and Afghanistan vets are destined to be obscured by larger matters dealing with policy and politics. Pundits are and will continue the dialogue over the war, but beyond the screen of media chatter and analysis, the men and women in uniform will return to an America ill prepared for them.

While they won’t face the open hostility many Vietnam vets faced, they will confront isolation and possibly suffer the despair that accompanies their separation from their buddies. Those who actually fought will bring with them the sense of loss, perhaps of futility, and perhaps the guilt of having survived when others died. I would hope that they, because of advances in technology, will keep in touch with one another for support. My teammates and I lost contact for 34 years.

What are the key lessons the nation should have learned in Vietnam? Did it?

The military learned some strategic lessons from Vietnam, but the government seems to have learned few. We still sink billions of dollars into corrupt regimes, money never properly tracked, money that will never be recovered. We haven’t yet grasped that any commitment to battle will likely not result in swift victory or even a satisfactory outcome.

What the government should have learned more than any other lesson is that military commitment and war will inevitably create a mess and that Americans don’t have the patience for messes. We elect those who seem too quick to use the military, or those to weak to use it.

I fully believe that if Jimmy Carter had the guts to drop a battalion of the 82nd Airborne Division on the embassy in Tehran, they would have successfully freed the hostages and the military would have figured out how to extract them, and our political position in the Middle East would have been greatly altered.

On the other hand, our invading Iraq was a disaster of bad policy and bad thinking. Thankfully, the one thing this nation has learned from the lessons of Vietnam is to honor those who serve or at the very least, treat them like human beings. That, I guess, is progress.