Once again, the Congressional Research Service has badgered a federal agency – in this case the Department of Veterans Affairs – and come up with snapshots about how U.S. vets seeking VA services are faring (CRS reports are not officially released to the public – dammit, you paid for them, and Congress works for us, so why does Steven Aftergood of the Federation of American Scientists’ Project on Government Secrecy have to release them after snagging them from his own secret Deep Quote?)

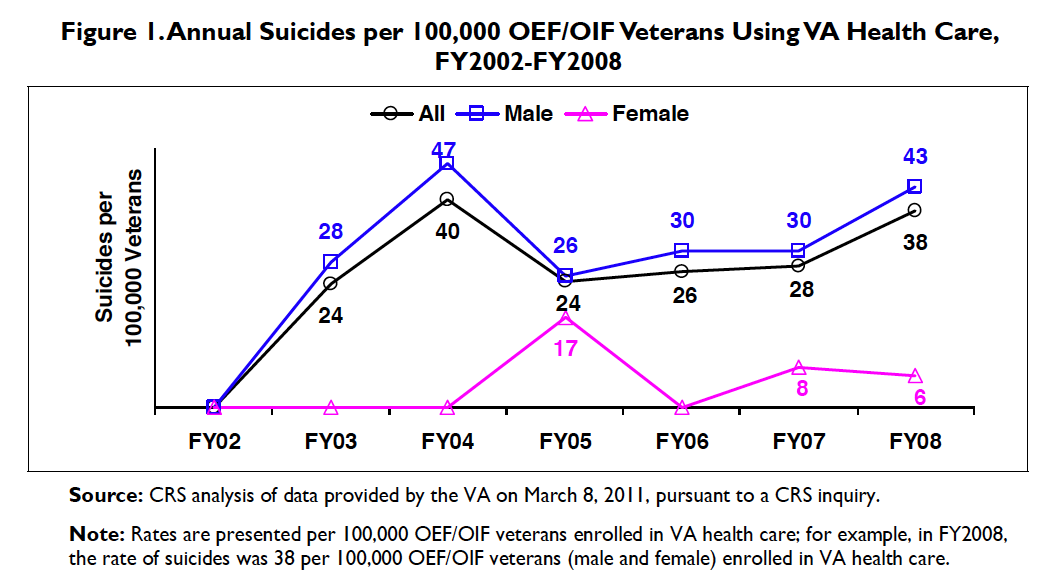

Anyway, the data are murky – there are a lot of caveats in the report – but they make clear a couple of things: suicide among vets spiked in 2004, to roughly double the national rate, in the initial year following the start of the Iraq war. By 2005, the rate among male troops fell by nearly half, while the rate among women skyrocketed. Since then, the rates have steadily crept back up close to 2004’s record toll (through 2008, the most recent year the VA apparently was able to turn over to the CRS).

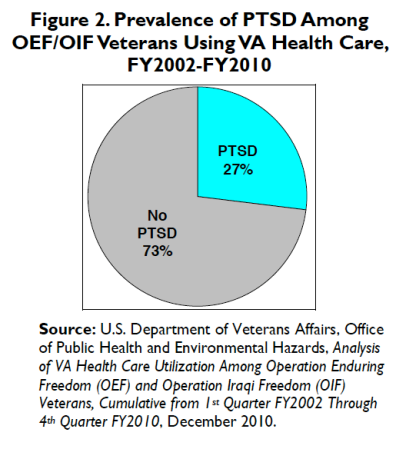

That’s the bad news. The good news, relatively speaking, is that post-traumatic stress disorder among all Afghanistan and Iraq veterans seeking VA health care from 2002 to 2010 was diagnosed in 27%. “No PTSD — 73%” seems like good news, even if it means more than 150,000 vets have been diagnosed with the condition.

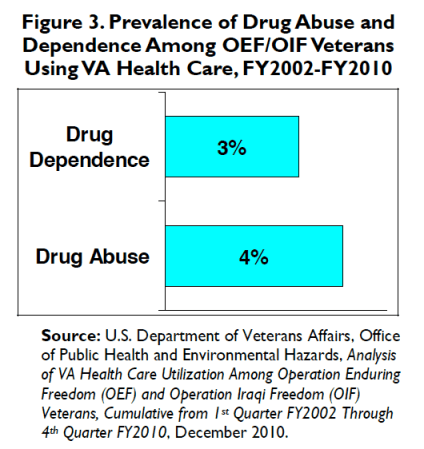

Finally, only 3% of veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq seeking VA care were drug dependent (4% were found to be drug abusers). That too seems like a relatively low number, as does the 7% said to be alcohol dependent. (“The prevalence of alcohol abuse,” the report notes, “was not provided.”)

The report doesn’t put these data in any context; it is simply trying to nail down numbers that can be tough to get and, even in the best cases, can be notoriously slippery once obtained. Between 2002 and 2010, 1,250,663 veterans who served in the two wars left the service. About half of them – 625,384 – sought VA health care after they got out of uniform.

“The numbers provided by the VA should not be extrapolated to all Operation Enduring Freedom [Afghanistan]/Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans, or to the broader veteran population, because OEF/OIF veterans using VA health care are not representative of all OEF/OIF veterans or the broader veteran population,” author Erin Bagalman noted. “Veterans who use VA health care may differ from those who do not, in ways that are not known. Potential differences include (among other characteristics) disability status, employment status, and distance from a VA medical facility.”