This illustration is not meant to imply Pakistan is operating Predator drones.

Shortly after 9/11, the Central Intelligence Agency began secretly killing suspected Taliban and al Qaeda militants in western Pakistan with Predator drones. The Pakistani government was so eager to hide the CIA’s fingerprints that it said the attacks were the work of the Pakistani government.

After years of such mysterious strikes, it became increasingly clear that it was the U.S. government that was conducting them. As that truth became increasingly undeniable, Islamabad began complaining ever more loudly about the Americans infringing on their national sovereignty.

A pair of drone strikes in Pakistan’s tribal belt last month killed nine people, including a pair of senior al Qaeda leaders. Pakistan made its rote complaint to the U.S. embassy.

But the U.S. says – although you should take this with a grain of saltpeter – that it hasn’t launched any drone attacks in Pakistan since January.

The New York Times reports from Islamabad Tuesday that at least one, and perhaps both, of the strikes were most likely carried out by…the Pakistani government. Pakistan is known to have been working on drones capable of firing weapons; Pentagon officials say they do not know what kind of weapons might have been used in the February strikes.

This is all, of course, a part of the slipperiness of drone warfare. It could be a sign that the virtual U.S. monopoly on armed drones is eroding. It is going to happen; the only question is when.

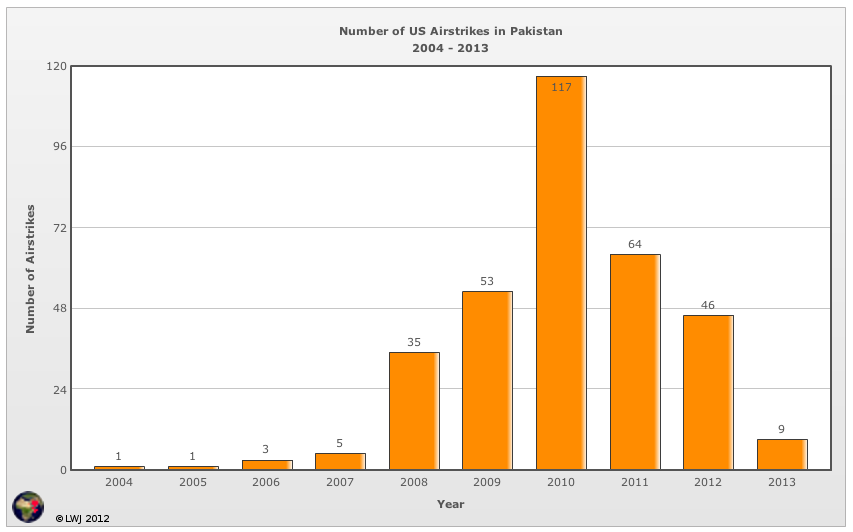

The number of drone strikes in Pakistan attributed to the U.S. by the independent Long War Journal has dropped sharply in recent years.

Beyond that, it’s important to note that Washington and Islamabad have different enemies in Pakistan’s tribal regions. There’s long been a tug-of-war that sometimes has boiled down to this: Pakistan winks at U.S. drone strikes on its territory against targets the U.S. wants taken out, in exchange for the U.S. hitting targets selected by Pakistan.

The U.S. targets insurgents dedicated to retaking Afghanistan, while Pakistan goes after those more interested in taking over Pakistan. They are not the same. (Think of it as a new form of literal takeout: I’ll have one from Column A, and he’ll have one from Column B.)

More important, in the long run, is determining the paternity of the trigger-puller. When the U.S. was the only nation flying – and firing – drones, it wasn’t hard to figure out who was doing the shooting. But we’re moving quickly into more complicated airspace, where unmanned aircraft, capable of remote operation from hundreds of miles away, are going to make it tougher to know who’s the killer.