Retired U.S. Air Force aircraft consigned to the "boneyard" at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Ariz.

President Obama will submit a new five-year spending plan for the entire federal government in his annual budget message to Congress later this month.

Included in his message will be the Pentagon’s five-year spending plan. The new plan covers Fiscal Years (FY) 2014 to FY18, and FY14 will begin in October 2013.

That means the last year of this plan, i.e., FY18, will begin in October 2017, or nine months after Mr. Obama has left the White House and moved on to greener pastures.

So, although the President has submitted a plan that includes budget details for FY18, two-thirds of that budget will be executed, and no doubt modified, by his successor as well as unfolding events.

In other words, Obama can only be responsible for only the first four years of his new five-year plan — i.e., FY14 thru FY17.

Lets take a look that these years.

The new defense plan will embody a reduction of about $140 to $160 billion over the comparable four-year period in the five-year plan Obama sent to Congress last year (i.e., the FY13-17 plan).

The looming possibility of a budget sequestration in March, however, could lop off another $50 billion per year, or a total of about $200 billion between FY14 and FY17 of the new plan.

Assuming the sequester goes into effect as scheduled on March 1, we are looking at a total reduction over Obama’s second term of about $360 billion when compared to the four common years of last year’s plan. It is this cutback that outgoing Defense Secretary Leon Panetta is peddling as a doomsday scenario that will turn the United States into a second-rate power.

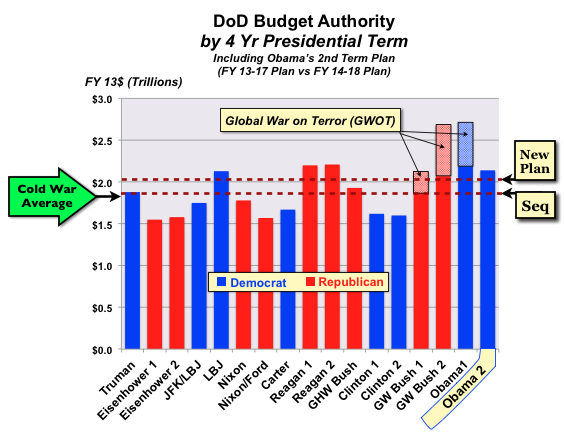

The chart below places Panetta’s claim into the context of past defense budgets. I have aggregated these budgets into the four-year totals corresponding to each presidential term since Harry Truman’s second term began 64 years ago in 1949 (FY1950). Bear in mind, the effects of inflation have been removed and these four-year totals are presented in trillions of FY13 constant dollars.

Several other points need to be clarified when interpreting the information contained in this figure. First, note that the Korea and Vietnam Wars were funded out of what is now known as the base budget (denoted by the solid colors), whereas the so-called global war on terror has been funded by supplemental emergency appropriations, which are added each year and not planned into the future. These supplementals are denoted by the lightly shaded colors in the chart.

Second, Obama’s four-year total for the base budgets for FY14 thru FY17 — i.e., his second term — is depicted by the rightmost blue bar with the yellow “hockey stick” labeled “Obama 2.” This bar says nothing about the war on terror, which will be funded on a pay-as-you-go basis, whereas Korea and Vietnam and all our other wars were included in the base budget.

Third, bear in mind that the new plan has not been released. The blue bar labeled “Obama 2” depicts the four-year total for FY14-17 that was included in last year’s FY13-17 five-year plan. The yellow box labeled “New Plan” givens the total that will be in those years when this plan is submitted to Congress later this month. The yellow box labeled “Seq” depicts the further reduction that would take place over these same four years, should the budget sequester be triggered.

Fourth, the two horizontal dashed lines compare the budget totals for the new plan and the sequester to those of earlier presidents stretching back to Truman and the dawn of the Cold War. The green arrow on the left side of the figure enables us to compare the four-year totals of the new plan and the sequester, to those averaged during the Cold War between the first fiscal year of the second Truman administration and the collapse of the Soviet Union by the end of the George H.W. Bush administration.

The chart shows us how the new plan lops off between $14o and $160 billion (or about $35-$40 billion per year for four years) from the four common years in last year’s plan. According to news reports, this reduction will cause the Air Force to cut back 286 aircraft from a total aircraft inventory of about 5,500 aircraft, and the Navy to reduce the increase in the growth of its battle fleet from the current level of 287 to 313, to a reduced goal of 306. Members of Congress have already expressed concern over these cutbacks, although they insist on a sequester unless Obama slashes social programs. Panetta has already signed off on these changes, so presumably these reductions will not produce a doomsday scenario.

The New Plan in Context

Note that the total of the Obama 2 budgets is approximately equal to that that of the LBJ administration during the Vietnam War, and almost equal to those of the Reagan 1 and 2 administrations (especially when one accounts for the uncertainties implicit in the inflation adjustment).

But if this year’s budget-driven reductions were made from comparable levels during the Johnson and Reagan administrations, the quantity reductions would have come from a much larger base: the Air Force quantity reductions would have been measured against its far larger inventories of about 13,000 aircraft and 8,300, aircraft respectively. Similarly, if the reduction in the Navy’s goal of 313 to 306 ships is compared to size of the fleets the Navy averaged during the Johnson and Reagan administrations, there would be a reduction from 910 and 570 battle-force ships, respectively.

In other words, the proportional severity of today’s force cutbacks today is far more a function of shrinking inventories than of shrinking budgets.

The shrinking inventories are a reflection of the simple fact that the unit costs of buying and operating our weapons are increasing much faster than budgets. That’s true even when those budgets increase rapidly, as they did in the early 1980s, and the especially during the last decade. This is more a problem of management incentives and bureaucratic game-playing, as I have described detail repeatedly since I began studying these problems in the late 1970s (see, for example, here, here and here).

Sequester

The yellow box in the chart, repeated here, labeled “Seq” is Panetta’s doomsday scenario. This is the terrifying budget sequester.

Note that the sequester would reduce the four-year total of Obama’s base budget to level of Harry Truman’s Korean-era budget total, which, we should remember, was sufficient to support 960 ships, about 15,000 aircraft, and a high-tempo Korea War in which we maintained a deployment 300,000 U.S. troops and sustain it by rotating 5.7 million troops thru the Korean theater.

This was a war where we suffered 36,000 killed in action, lost more than 1,400 aircraft, and flew well over 200,000 combat sorties. Oh, and I almost forgot: there was sufficient money left over for the Air Force to buy more than 15,700 airplanes, for the Navy to purchase more than 8,000 planes, and for the Army to buy almost 9,000 tanks.

Note also that the doomsday budget is also approximately equal to that averaged during the Cold War.

But in the post-Cold War world of today, the current defense secretary would have us believe that the same level of level of spending would create a doomsday scenario for the Pentagon’s ambitions to:

— (1) defeat a few thousand lightly armed jihadists, who main firepower is the kamikaze-like suicide bomber, and

— (2) fund the pivot toward China to start a new Cold War against a country that spends about $143 billion on defense, only about 30% of the U.S. defense budget, assuming that budget is in fact reduced to the sequestered level.

Does anyone see a problem?

So, with this in mind, I want to respectfully submit two closely connected questions to Secretary Panetta, and his successor:

1. Sir, can you explain how a budget sequester that reduces future defense budgets to levels averaged during the Cold War can possibly produce a doomsday scenario for the far smaller forces of the post-Cold War era, particularly when there is no superpower threat to counter? Or is the question of spending levels really a question triggered by incentives and bureaucratic gaming fueling the greed for money and power of the factions within Military – Industrial – Congressional Complex?

2. Sir, Before answering my second question, consider please the following facts:

— (a) Stephen Friedman’s financial transformation panel, which was established in 2001 at the behest of Secretary of Defense, issued a report, Transforming Department of Defense Financial Management: A Strategy for Change, on April 13, 2001 that concluded the Defense Department’s accounting systems do not provide reliable information that “tells managers the costs of forces or activities that they manage and the relationship of funding levels to output, capability or performance of those forces or activities.”

— (b) You testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee on page 3 of your 14 February 2012 budget request that the Defense Department will not be able to meet the legal requirement for audit readiness until 2017 (and by implication will not be able to solve the problem posed in 2001 by Friedman until that time).

With (a) and (b) in mind, my second question is this:

How can you possibly claim the sequester will now make America a second-rate power, when your own management information system cannot reliably connect accounting inputs to performance and capability outputs, particularly in this case, where the sequester will only reduce the defense budget to levels averaged during the Cold War?