“Let’s say those Palestinians who have engaged in acts of terrorism, perhaps in retaliation against Israel for Israel defending itself,” the Republican from Utah asked, “do they have a legitimate gripe?”

Hagel responded that “terrorism can never be justified under any circumstances.”

Lee continued, bringing up the possibility that Israel might withdraw to its pre-1967 borders. “Do you view that as a tenable solution?” he asked Hagel. “Do you believe such borders are militarily defensible?”

This went on and on. In fact, Lee—by himself—made reference to Israel and its security a total of 16 times.

Why is this important? It’s important because Lee never mentioned Afghanistan and the 66,000 U.S. troops at war there.

And Lee was not alone.

Freshman Republican Senator Ted Cruz of Texas also grilled Hagel about Israel. He mentioned the Jewish state 10 times—without ever once referring to Afghanistan or the U.S. troops in combat there.

When it was their turn to question Hagel, GOP senators Roy Blunt of Missouri and Roger Wicker of Mississippi each referred to Israel in a half dozen instances. Neither mentioned Afghanistan.

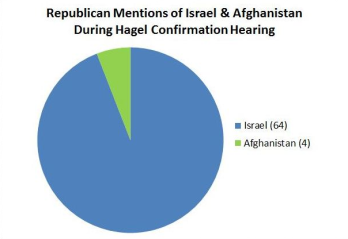

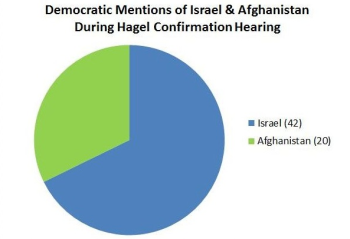

In nearly eight hours of interrogation and testimony, Israel and its interests were referred to by the Senate Armed Services Committee a total of 106 times. On the other hand, there were a mere 24 references made to Afghanistan and the Americans fighting there—most by Democratic Senator Carl Levin, chairman of the committee.

Nuclear-armed Pakistan—where the U.S. frequently targets militants with drone-launched Hellfire missiles—barely merited mention at all.

It’s difficult to interpret this message any other way: the Senate Armed Services Committee—particularly its Republican membership—is more concerned with the apparent American defense secretary’s relationship with Israel than with the future of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the fate of U.S. troops engaged in both locations.

We are approaching a host of critical and delicate decisions on how many — and how fast — U.S. troops should be pulled out of Afghanistan. Yet, after more than a decade at war there — and nearly 2,100 U.S. lives lost — the people charged with overseeing the operation seem no longer interested.

While Israel is a strategic ally in a precarious situation (the committee also frequently brought up Iran), at best, this sends a disheartening message to the American men and women serving down range, under hostile fire. After 11 years of fighting, committee members seem to have little concern for what the likely incoming defense secretary thinks of the situation.

Fatigue is a factor—both parties are more than ready to be done with the Afghan venture. But beginnings, and endings, of any enterprise are often the most important. If anyone has a right to be exhausted of this process, to be tired of thinking about it, living it, and troubleshooting it, it’s not senators in Washington. It’s the men and women who have fought—and are fighting—there.

After so much blood and treasure, it shouldn’t be too much to ask that the people who sent them there, and have kept them there, pay fuller attention to our ongoing hot war—even as it enters its final stages. It’s the least they could do for the soldier taking fire today.

Brandon Friedman is a veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan and author of The War I Always Wanted. He is a vice president at Fleishman-Hillard International Communications in Washington, D.C. Follow him on Twitter at @BFriedmanDC.