Killing -- before ultimately resurrecting. Canceling the B-1 bomber added a decade to the Cold War, Project Terminated's author estimates.

The Pentagon has long had a problem launching $10 worth of weapons when it only has $5 to pay for them. That leads to lots of fiscal fratricide inside the U.S. military, and it doesn’t do the taxpayers any favors, either.

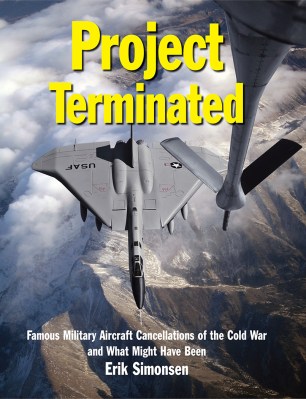

Erik Simonsen decided to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear by publishing a book dedicated to military aircraft that basically never made it off the ground, at least in terms of full-rate production. In Project Terminated: Famous Military Aircraft Cancellations of the Cold War and What Might Have Been, the California photographer-writer details big dreams that crashed into budgetary, political or technological hurdles before getting off the R&D runway. Battleland conducted this email chat with him last week:

What did researching and doing this book teach you about the way the Pentagon buys its weapons?

Our competitive system is certainly the best way to conduct Defense Department-buying of weapons systems. However, as in many other business structures, having the process function smoothly can be another story. I believe honest and open communications is paramount. This can help to avoid problems and facilitate teamwork between the government and contractors. Everyone should be aware of the technical challenges that may be encountered, and the benefits of deployment. A primary goal should be, ”no surprises.”

Critical priorities should be strictly adhered to such as, outlining as clear as possible the flight test schedule and program milestones. Unfortunately, people and corporations are reticent to report deficiencies, or poor performance until it’s too late. If there were more upfront communications many funding disasters and cancellations could possibly have been averted.

Certainly, with the Canadian CF-105 Arrow interceptor and the British TSR.2 medium-bomber program, there was very poor communications between government officials and the contractors. As my research revealed, both people and governments often fail to learn the lessons of history.

Why did you focus only on aircraft, and only on the Cold War era?

The book focuses on aircraft, but does include one space-related program that was cancelled in 1968 — the USAF/Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar manned spaceplane. Even though it was never built, the X-20 was an innovative design that would have introduced game-changing technology. I included it because of its potential impact on history.

There are two primary reasons for focusing on the Cold War. First, many of the most controversial cancellations occurred during the Cold War. Secondly, the Cold War was such a critical period in shaping post-World War II history.

In the media we quite often hear a common statement: “I suppose cancelling many military programs was OK, since we made it through the Cold War.”

It is true that we did make it through the Cold War, and unfortunately many people fall into this simplistic thought mode. Not everyone made it through OK. For millions of people living under communist rule in the Soviet bloc, continuing the Cold War resulted in prolonged suffering, and tens of thousands did not survive. For our courageous servicemen and women, and those of our allies, who lost their lives carrying out vital reconnaissance and other missions, it might as well have been a “hot war.”

It is important to understand that at the time, a program procurement that could possibly advance U.S. technology in order to deter the Soviet Union was worth taking some risk. It might have possibly shortened the Cold War.

Your subtitle is “what might have been.” Tell us.

In just about every subject area there is always a moment when people think about “what might have been.”

Worldwide, the aerospace industry has an enormous following of professionals, historians and enthusiasts. A book on cancelled programs offered an ideal opportunity to address the subject of “what might have been.” Throughout aviation history, there are so many variables, and when you consider how close some programs came to fruition only to be terminated, you have quite a menu for thought and creativity.

Project Terminated was an opportunity not only to write about, but to also visualize these historic aircraft that didn’t quite make it.

What common characteristics did you discern in the weapons cited in Project Terminated?

I would say there was a trend to quickly test new technology.

This was quite common during the Cold War period – the primary reason being the Soviet threat to world peace. Yet, despite a high degree of risk in introducing untested technology, there were varying degrees of government insistence to perform. As a result testing was expedited, and many anomalies occurred.

In the U.S., Canada and Great Britain, government officials quickly become impatient when schedules weren’t met. Many individuals really didn’t understand aircraft design, construction and flight-testing, yet they controlled the budgets.

Another common thread for impending cancellation was a lack of communications that resulted in uninformed political pressure.

The exceptional Northrop F-20 Tigershark fell victim to domestic/international politics and bad timing. In the case of the Northrop YB-49A flying wing it was the flight control systems. Jack Northrop’s design was ahead of its time – this was verified decades later, with the B-2 flying wing operating with computerized flight controls.

The Rockwell XFV-12A lift-design was not producing adequate thrust for VTOL (Vertical Takeoff and Land) – the book suggested a shift to a VSTOL (Vertical Short Takeoff and Land) mode. VSTOL has proved to be very successful today.

A confirmed non-listener to military experts — Defense Secretary Robert McNamara — simply did not want the Rockwell XB-70 Mach 3 strategic bomber, Lockheed F-12B Mach 3 interceptor, or the Boeing X-20 manned spaceplane. In the end, some programs just had opponents that no amount of briefings or reasoning could persuade.

Is there a pattern to why weapons are terminated? If so, what is it – and how early does it tend to show up?

An early distress pattern begins when a program is not meeting its test schedule. This is underscored by a lack of understanding by politicians of the technology and risk.

Another driving factor, and very relevant today, is escalating cost increases. Whether this occurs during flight test, or production, there is a low tolerance for this.

If a program dramatically exceeds its original projected cost, it quickly becomes a target no matter how critical it is to the defense community. Poor communications exasperates this type of situation.

Give the Pentagon a grade for the way it buys weapons.

I would give it a C.

One on-going problem today occurs when the losing contractor can protest the Pentagon’s win decision. There, of course must be a challenge opportunity for losing bidder, but today that practice is being abused. This has slowed the acquisition process and greatly increased Defense Department weapon-systems costs.

Another annoying difficulty associated with cost increases, transpires after a contract award. At that stage, the winning contractor has carefully calculated the pricing for a production run. The snag concerns the final-unit number buy, and it’s fair to say that this number may undergo limited modification. However, decreasing the unit numbers purchased on a grand scale is a driver that can lead to disastrous cost increases.

As an example in 1981, 132 Advanced Technology Bombers (B-2) were ordered – in the end, only 21 aircraft were built, resulting in an enormous increase in the cost of each B-2 stealth bomber.

In 2009, the very capable F-22 Raptor was capped at 187 aircraft, down from an original announced buy of 650 units. With the recent advances of Russian and Chinese fifth-generation fighter development, the F-22 production cap might become a future discussion for historians.

This obvious catalyst for cost increases is not “rocket science” but basic economics.

As pointed out in several chapters, this practice seems to perpetuate though the decades, and continues today with many important lessons from history not learned. Today, there are significantly improved communications, allowing the Pentagon to be thoroughly informed on the bidding contractors and programs under development. Additionally, aggressive steps are being taken to resolve procurement deficiencies. Yet, there’s much work to be done.

Give the defense industry a grade for the way it builds weapons.

I would give it a B+.

The defense industry has within its ranks the most dedicated and brightest talent, and they build and deploy the finest weapon systems in the world. However, arriving at the final product, while working within our procurement system, is where roadblocks arise.

Eventually, solutions will be introduced to improve our acquisition process, thus allowing contractors to bid and work unhindered. Conversely, product developmental problems that arise must be addressed quickly and truthfully. Thinking of history, we will never return to the days when Kelly Johnson autonomously directed Lockheed’s Skunk Works. That organization got things done and products, such as the SR-71 Blackbird, were stunning breakthroughs in technology.

What accounts for the discrepancy in your assigned grades?

The discrepancy is that the Defense Department, with a requirement to purchase the best products, and the contractors, are both operating within a challenged procurement system. Over the past several decades, mergers and consolidations within the aerospace industry have reduced competitive choices for the Pentagon.

Additionally, with current shrinking Defense Department budgets there are fewer new programs in the pipeline. Such a scenario creates a difficult business environment. Today, smart companies are diversifying and also seeking out foreign defense business opportunities.

Do you think the lessons in your aircraft cancellations apply to other kinds of weapons? Why or why not?

I believe the lessons are applicable to other types of weapons procurement. Some of the barriers that I’ve mentioned can be prevented with open communications, and having a stringent review and monitoring process in place.

One additional difficulty to be avoided is known as “requirements creep”. Often associated with the defense-acquisition system, the term describes the addition of new technical or operational specifications, after a requirements document has been approved by the appropriate validation authority. “Requirements creep” can seriously delay schedules and increase cost.

I would like to add that patience can be a virtue.

In 1958, there was a critical requirement for a new reconnaissance capability to monitor the Soviet Union. President Eisenhower initiated development of the first space-based reconnaissance system, known as the Corona Project. However, the satellite program was not successful in returning imagery from space until its 15th flight. This initial success was followed by three additional failures.

How many programs today would survive with that track record? Yet Corona persevered, and became the forerunner of the sophisticated space assets we have today. We must have patience in the development and testing process.

What weapon was cancelled that you think shouldn’t have been?

One program cancellation that stands out, especially in light of the U.S. being at a critical period of the Cold War, is the B-1 bomber program.

Cancelling this major strategic program by President Carter in June 1977 occurred at a time when Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev was significantly increasing spending on weapons, and directing new expansionist strategies. In the eyes of the Soviets, the U.S. was signaling that it was not serious in containing Soviet adventurism. Among other events, within two years the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan.

The U.S. most likely added 10 years to the duration of the Cold War with the B-1 cancellation decision.

The B-1 was already being flight tested, and was not considered a technical challenge. It could have been fielded rather quickly.

Yet, the Carter Administration officially proclaimed that the B-1 was not needed, and that a new technology stealth bomber was being developed. Actually, it was 12 years before the B-2 stealth bomber flew. The naiveté of the B-1 cancellation was confirmed in 1980 with the election of President Reagan. Reagan initiated a “peace through strength” policy by beefing up U.S. strategic deterrence forces that included the B-1B bomber and the Advanced Technology Bomber (B-2). Acquiring the B-1B quickly negated the Soviet’s ‘first strike’ capability. This started the initial crack that eventually ended the Cold War.

Also under President Reagan, the final push in helping end the Cold War was the U.S. proceeding with the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) program, known in the media as “Star Wars.” The missile defense system threatened to negate Soviet nuclear-armed ICBMs, in which they had invested enormously in order to threaten the U.S. and our allies. Gradually, the Soviets were unable to compete technologically and economically.