The new 100-bed provincial hospital under construction in Gardez, Afghanistan.

The future of Afghanistan begins at the end of next year, after U.S. combat troops depart and Afghan forces take over for keeps.

After spending more than a half-trillion dollars, it’s difficult keeping track of the state of the Afghan security forces – army and police – amid conflicting claims about how well, and how many, of them have been trained.

So let’s pick a simpler yardstick – the hospitals the U.S. is building for the people of Afghanistan. There, concrete measures – square footage built, beds provided, how much they’ll cost to operate – are easier to assess.

Unfortunately, like much that has happened in Afghanistan since the U.S. invasion less than a month after 9/11, American heads – if not hearts – have been in the wrong place.

Last week, the federal Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), examined a pair of hospitals the U.S. Agency for International Development is building in the eastern part of the country. It found the hospitals too big for Afghanistan to handle.

(MORE: Survey Reveals Little Change in Afghan Social Attitudes Despite Western Presence)

SIGAR John Sopko’s staff details a tragedy of errors, where USAID failed to determine the Afghan government’s ability to operate the two hospitals, and where construction began a full year before USAID coordinated the final design plans with the Afghan Ministry of Public Health (MOPH). A 100-bed provincial hospital is being built in Gardez in Pakitia province, and a second 20-bed district hospital is being built in Khair Khot in Paktika province. “USAID’s $18.5 million investment in these new hospitals,” the inspector general reports, “may not be the most economical and practical use of these funds.”

To put it mildly.

Among SIGAR’s findings:

— The Gardez hospital is 12 times larger than the hospital it is replacing. “A Ministry official stated that they do not need such a large hospital, which will require additional staff for cleaning and security and further strain funding available for future hospital operations,” SIGAR reported.

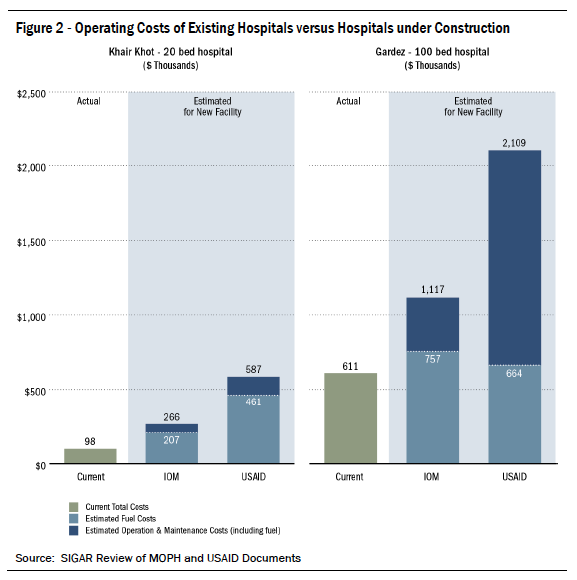

— Both will cost roughly five times as much to run as the medical facilities they are replacing:

The existing Gardez hospital has annual operating costs, including fuel, of about $611,000, and USAID estimates that annual fuel costs alone for the new hospital could be as much as $3.2 million. Similarly, the existing Khair Khot hospital has annual operating costs of about $98,000 and USAID estimates that annual operation and maintenance costs alone for the new hospital will be about $587,000. Neither USAID nor MOPH has committed to provide funding to cover the additional operating costs of the new hospitals.

There was a lack of coordination between USAID and the Afghan health ministry:

In March 2013, a USAID official told us that the Ministry twice provided documentation stating that it would be able to operate and maintain the new facilities once completed…Ministry officials told us that the statements from the Minister were not based on detailed analyses of operation and maintenance costs, but on general assumptions regarding the Ministry’s ability to fund operations for the new health facilities in the future. Moreover, we found no evidence that USAID had conducted any analysis to determine whether the Ministry had the ability to operate the health facilities…USAID also could not provide documentation to indicate that the agency’s review and approval of the design plans for the Gardez and Khair Khot hospitals took into account the higher operating costs estimated for the new facilities or the Afghan government’s financial capability to maintain them once completed…

“I’m all too familiar with how shocking the wastefulness has been in Afghanistan,” Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., noted at an April 25 House Armed Services Committee hearing into Afghan reconstruction. “It’s abominable what’s going on.”

“Between 2001 and 2010 alone, Rohde notes, Congress cut USAID’s staff by 30%,” notes a review in Sunday’s New York Times of reporter David Rohde’s new book, Beyond War: Reimagining American Influence in a New Middle East. “Over the same period, it doubled the agency’s budget. The result: foreign policy by contractor. Suddenly required to spend vast sums bringing democracy and prosperity to Afghanistan and Iraq, America’s emaciated civilian agencies could do little more than write huge checks to the megacontractors that grew fat off the `war on terror,'” Peter Beinart wrote in his review.

USAID disputed the SIGAR report, saying it failed to take into account “the highly complex public health system in Afghanistan.” It said it has helped provide health care for more than 11 million Afghans, and trained more than 21,000 healthcare providers. Under USAID programs, prenatal health care for Afghan women jumped from 16% in 2003 to 60% in 2010, and reduced maternal mortality by 80% and infant mortality by 62%.

There is no denying the U.S. has played a major role in improving Afghan health. The question is how much more could have been done if the Americans had been more willing to do things the Afghan way. The problem, it turns out, is not so much USAID’s, as it is an American notion that it is possible for Washington to blueprint and build a foreign land torn by decades of war of which it knows little. After all, the SIGAR report noted, the Pentagon has also experienced similar growing pains in building a new Afghan hospital in nearby Khowst.

“This 100-bed hospital, completed in 2011, could not be fully used due to excessive fuel costs incurred for the 450- and 500-kilowatt generators that were originally installed,” the SIGAR report says. “Ministry officials calculated that the fuel costs needed to operate these large generators were approximately 10 times higher for the new facility than they were for the old facility. However, no additional funding was made available to accommodate the major increase in fuel costs.”

The Afghans bought a pair of smaller 132-kilowatt generators to power the Khowst hospital to lower their fuel costs. “These officials stated that the smaller generators did not have sufficient capacity to power the entire hospital,” the report adds. “As a result, only about 35% of the space in the new Khowst hospital was operational at the time of our audit, and the two larger generators purchased for this project were not being used.”

One thing’s for sure: whatever’s plaguing the U.S. efforts to bring health care to Afghanistan is contagious.