Pakistani tribesmen gather for funeral prayers before the coffins of purportedly innocent civilians killed in a 2011 U.S. drone attack in North Waziristan.

The U.S. government post-9/11 has taken to hiding military missions – not only from the U.S. public (“War in Pakistan? What war in Pakistan?) but also from those it seeks to kill, in order to prevent another such attack. Rather than rely on armed forces, with all the baggage they can bring to battlefields — both real and political — the nation increasingly has opted to transform the CIA and America’s special operations forces into man-hunting and killing machines.

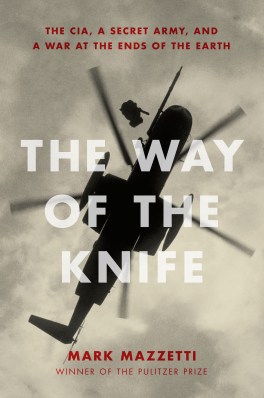

It’s a double-edged sword, as author Mark Mazzetti makes clear in his book out Tuesday, April 9: The Way of the Knife: The CIA, a Secret Army, and a War at the Ends of the Earth. Is this the best way – the only way? – for the U.S. to defend itself? Mazzetti, a Pulitzer Prize-winning national-security reporter at the New York Times (which published an excerpt from the book Sunday), conducted this email chat with Battleland on Monday:

Why did you title your book The Way of the Knife: The CIA, a Secret Army, and a War at the Ends of the Earth?

The title is a departure from an analogy once used in a speech by CIA Director John Brennan, when he was the top White House counterterrorism official.

He said that, in contrast to the big wars in Iraq and Afghanistan where the United States has used the “hammer,” America can use the “scalpel” in places beyond war zones.

But as I write in the book, the scalpel analogy implies that this is a way of war that’s without costs or blunders — a surgery without complications. As we’ve seen, so many times that’s not the case.

So, I chose The Way of the Knife. Knife fights tend to be a good deal messier.

Sum up the main conclusions of your book.

The purpose of the book is to try to tell as much of a history as possible of the “secret wars” since 9/11, the wars in Pakistan and Yemen and parts of Africa.

The CIA has been at the forefront of these wars, and as a result it’s a fundamentally changed place. The emphasis for so many years has been on man-hunting and killing, as opposition to traditional espionage.

At the same time, you’ve seen a mirror image at the Pentagon: it has become more like the CIA. In the early days after 9/11, Donald Rumsfeld was angry that he couldn’t send American troops to places that weren’t declared war zones, and he began a push to broaden the military’s authorities to gather intelligence all around the world.

Based on your reporting and research, is the U.S. becoming too enamored of waging war in the shadows? Why or why not?

I as try to show in the reporting, two successive American presidents have become quite enamored of these shadow wars.

They began under a conservative Republican and have been embraced and arguably expanded by a liberal Democrat.

It’s risky when secret operations become the default way the United States wages war, because there are real questions about transparency and accountability. Throughout American history, U.S. presidents have relied on the CIA to carry out covert actions because, well, they were secret and the White House never had to own up to them.

But, as we have seen, a lot of those covert actions went horribly wrong. When decisions are made in secret, with only a small number of people giving advice about the wisdom of paramilitary operations, there is an inherent risk that those operations could come back to haunt the United States.

Does this kind of warfare make more sense than conventional war when confronting non-state actors?

What the U.S. confronted after 9/11 was that there are plenty of places where the 101st Airborne can’t go.

Countries like Pakistan and Yemen are deeply suspicious of the American military, and their governments wouldn’t allow conventional American troops to be hunting around looking for al Qaeda operatives.

It was one of the reasons that Rumsfeld pushed so hard to expand the military’s special-operations capabilities, and as I said, the Pentagon’s authorities under Title 10 to do man-hunting beyond traditional war zones.

How would you grade the CIA’s kinetic work, and on balance, does firing Hellfire missiles from drones work?

There is good evidence that over more than a dozen years, the CIA has become more accurate firing Hellfire missiles from Predators and Reapers. The technology has advanced, allowing the pilot to limit damage surrounding the target.

At the same time, the operation is only as good as the intelligence, and as we’ve seen far too often since the September 11 attacks, there were strikes based on bad intelligence and civilians were killed.

In Pakistan, it appears that intelligence networks have vastly improved and that there are fewer civilian casualties than there were a few years ago, but it’s still incredibly difficult to assess exactly how many people are killed in each strike, and who they are.

It’s very rare for officials in Washington, Sana’a, Islamabad or other places to publicly acknowledge who is killed in these strikes.

What was the most surprising thing you learned while researching and reporting The Way of the Knife?

I think the most surprising thing is how much the United States has relied on unconventional actors to wage this kind of warfare: foreign proxy armies, private contractors, and individuals who convince the Pentagon and CIA that they can get into “hard target” countries to gather intelligence.

It opens up the playing field to all sorts of colorful characters, many of whom I write about in detail in the book.

Will it sell more copies than 2012’s Counterstrike?

Ha!

Counterstrike is a terrific book, by two great reporters and great friends [fellow Times‘ reporters Eric Schmitt and Thom Shanker]. And, it’s now out in paperback, so everyone should buy it! The more people writing about these subjects, the better.