Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel at the National Defense University April 3.

As Pentagon watchers count down the days until the April 10th release of President Obama’s proposal for the fiscal year (FY) 2014 defense budget, Battleland’s Mark Thompson recently nicked Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel for claiming the military will have “significantly less resources than the department has had in the past”. In particular, Thompson wrote that Hagel’s claim is “flat-out wrong,” describing it as “a surprising statement coming from a defense secretary who served as a sergeant in Vietnam and knew balderdash, to put it politely, when he saw it.”

But upon closer examination, I’d argue that Thompson was too quick to dismiss Hagel’s claim.

My analysis of the Pentagon comptroller’s historical budget data, coupled with the Center for Security and Budgetary Analysis (CSBA) estimates of sequestration’s effects, suggests Thompson’s criticism of Hagel is off the mark in a number of meaningful ways.

First of all, Hagel’s claim is not “flat-out wrong.”

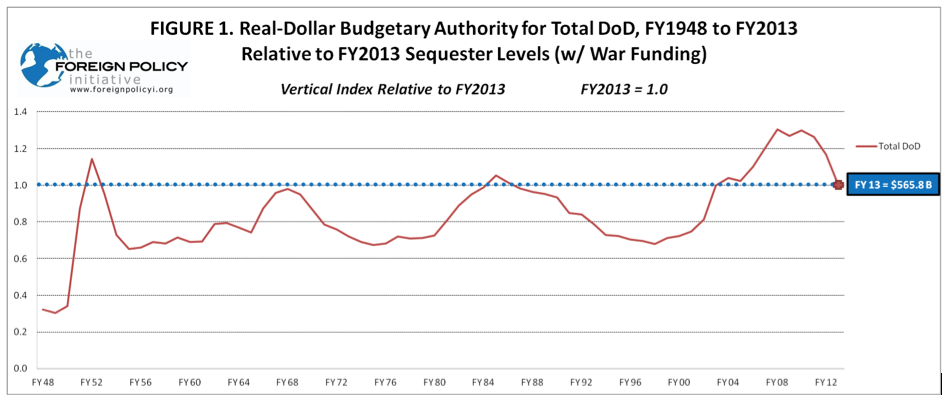

Accounting for sequestration’s automatic cuts, CSBA’s Todd Harrison calculates that total budgetary authority for the Pentagon, including war funding, will total $565.8 billion in FY 2013. If we compare that amount to what the military has annually spent in inflation-adjusted dollars during the post-World War II period, we find that the Pentagon’s FY 2013 budgetary authority has been exceeded in 12 individual fiscal years since 1948—namely, in FY 1952, from FY 1985 to FY 1986, and from FY 2004 to FY 2012. (See Figure 1.)

In other words, current defense spending was eclipsed during one year of the Korean war, two years of the Reagan peacetime military build-up, and most of Bush’s and Obama’s wartime presidencies.

Second, the military’s significantly fewer resources become more apparent when you look into the details of the Defense Department’s specific accounts.

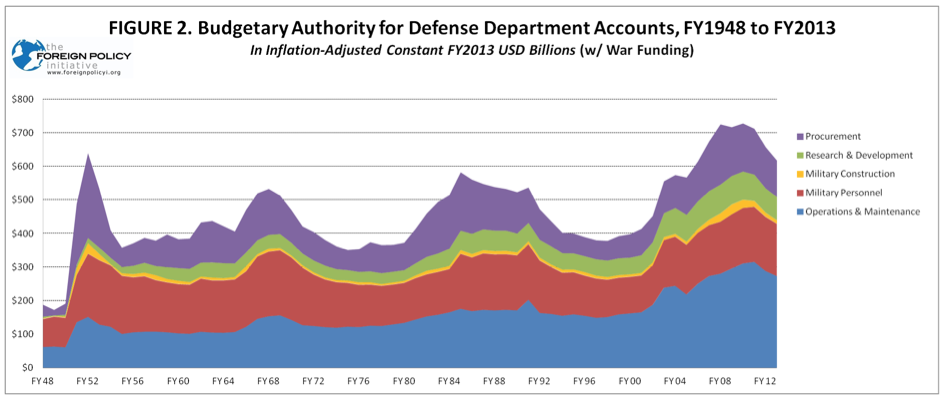

For more than a decade, the Pentagon has dedicated increasingly more of its budget in real dollars to its “operations and maintenance” account, which is used to train and ready troops, keep up equipment and facilities, and operate military forces. (See Figure 2.)

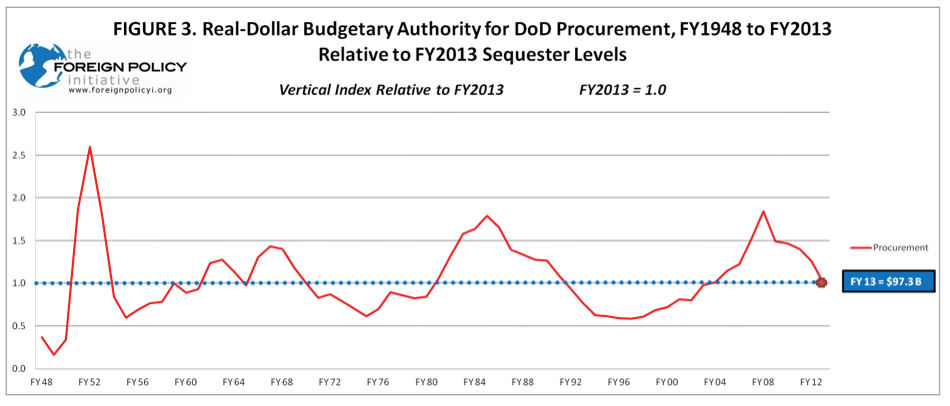

But the Defense Department, in turn, has dedicated fewer resources to its so-called investment accounts—in particular, to its procurement account, which it uses to modernize the military’s ships, planes, tanks, and other weapons platforms. If we account for sequestration cuts, the Pentagon’s budgetary authority for procurement in FY 2013 has been exceeded in 32 individual fiscal years since 1948—namely, from FY 1951 to FY 1953, in FY 1959, from FY 1962 to FY 1964, from FY 1966 to FY 1970, from FY 1981 to FY 1991, and from FY 2004 to FY 2012. (See Figure 3.)

In other words, current spending on defense procurement was exceeded during most of the Korean War, one year of the Eisenhower presidency, all of Kennedy’s military build-up, most of Johnson’s wartime presidency, almost all of the Reagan and Bush presidencies, and most of Bush’s and Obama’s wartime presidencies.

Third, defense sequestration will further diminish the Pentagon’s available resources in real terms over the next decade.

To begin with, sequestration’s automatic cuts are indiscriminately slashing the entire account for “national defense spending”—roughly 96% percent of which is consumed by the Defense Department—in FY 2013. Moreover, sequestration will be imposing significantly lowered caps on national defense spending (relative to what the Obama administration had earlier projected would be spent over the long term) for nearly a decade.

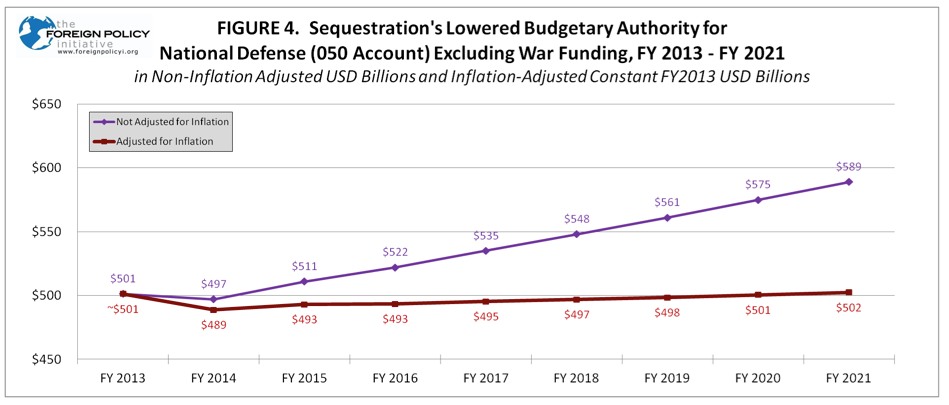

That said, some Pentagon observers are arguing that defense sequestration’s long-term spending caps—which limit budgetary authority for regular annual spending on national defense, but not for supplemental war funding—will not impose serious cuts on the military. For example, Thompson recently wrote: “What is true is that the projected rate of growth has been cut way back—and will keep being cut in the future if the nation’s political leaders fail to come to an agreement on a decade-long deficit-reduction package of $1.2 trillion.”

However, such arguments are incorrect, stemming from the tendency of some Pentagon watchers—for instance, the Washington Examiner’s Byron York or the Mercatus Center economist Veronique de Rugy—to depict projections of future defense spending solely in non-inflation-adjusted dollars. Indeed, as Figure 4 shows, when you look at sequestration’s spending caps on national defense spending in nominal dollars, it appears to “grow” over the next decade. But as figure 4 also shows, if you adjust for inflation, budgetary authority for national defense, in fact, does not grow in terms of real dollars under sequestration’s spending caps, but rather remains basically flat.

Fourth, the military’s diminished resources over the next decade becomes even clearer if we put sequestration’s spending caps over the next decade in historical context.

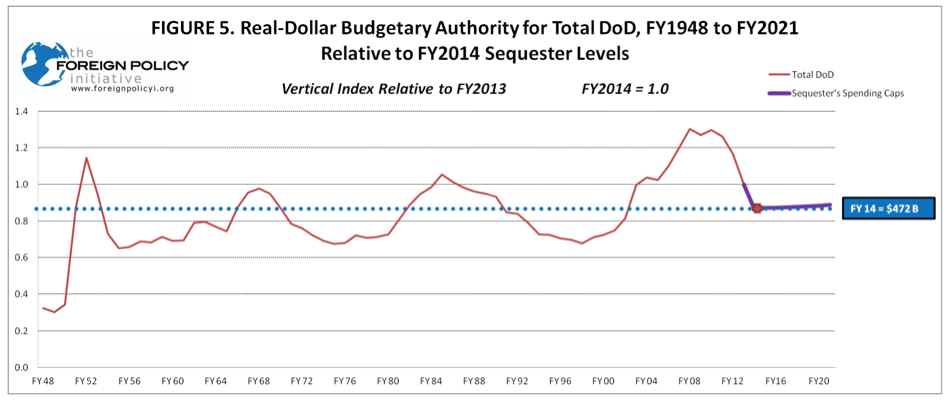

Sequestration’s caps on budgetary authority for the Defense Department—which, again, constrains regular annual spending and not war funding—limits Pentagon spending to roughly $472 billion in FY 2014. As Figure 5 illustrates, that amount has been exceeded in 27 individual fiscal years since 1948—namely, from FY1951 to FY1953, from FY1966 to FY1970, from FY1982 to FY1990, and from FY2003 to FY2012.

In other words, the cap for the FY 2014 defense spending was exceeded during most of the Korean War, most of Johnson’s wartime presidency, almost all of the Reagan’s peacetime military buildup, part of the first Bush’s presidency, and most of Bush’s and Obama’s wartime presidencies.

In sum, it appears that—contrary to Thompson’s criticism—Hagel’s claim that the Pentagon will have “significantly less resources than the department has had in the past” is not flat-out wrong. Indeed, the record shows that defense spending since FY 2010 has taken a real-dollar nosedive, the likes of which hasn’t been seen since the 1950s, and is going to be further exacerbated by sequestration. Consequently, as America’s defense institutions prepare to deal with the threats of ongoing international terrorism, nuclear proliferators like Iran and North Korea, China’s military rise, and other security challenges in the 21st century, they will have fewer resources they had during many intervals of the last seven decades.

It’s worth observing that, contrary to the prevailing stereotype, defense spending in real dollars has not spiraled in growth during the post-World War II era. Rather, as Figure 6 vividly shows, defense spending has remained comparatively flat when contrasted with total domestic spending, which, even in inflation-adjusted terms, has grown nearly exponentially.

In closing, despite Thompson’s dismissal of Hagel’s not-so-flawed defense-spending premise, his article’s larger reportage—about the need to reform the Pentagon’s acquisition costs and efficacy, curb the rising costs of the military personnel account, and find more efficiencies in the Defense Department’s command and support structures—is basically spot on. Yet so long as the prevailing stereotype about the spiraling and inexorable growth of military spending remains unchallenged, policymakers, lawmakers and the general public are likely to keep looking to defense cuts to avoid the hard choices required to genuinely constrain the major drivers of America’s deficit and debt.

Robert Zarate is policy director at the non-profit Foreign Policy Initiative, an independent group pushing to maintain U.S. military strength. He previously worked on national-security and foreign-affairs issues on Capitol Hill.