Many photographs were taken and documents created surrounding the assassination of Martin Luther King, which took place 45 years ago this week in Memphis, Tenn. But until recently, virtually nobody knew there was video taken of James Earl Ray, the man who was convicted of King’s murder, upon his arrest in London three months later.

On Thursday the Shelby County, Tenn., Register of Deeds — which had unwittingly been in possession of the tapes for decades — released remarkable footage that, though shot in grainy black and white and choppy in parts, provide a legal record of the early process of Ray’s arrest. The most poignant piece of footage is of Bill Morris, then the Sheriff of Shelby County, performing Ray’s formal arrest as the fugitive gunman was being extradited back to the United States.

(PHOTOS: The Day MLK Was Assassinated: A Photographer’s Story)

It’s a remarkable document not only for its historical significance but for the fact that Shelby County Sheriffs had thought to videotape the proceedings long before it was standard court practice. “They really had some foresight in doing this,” says Tom Leatherwood, Shelby County Register of Deeds. He explained that the county sheriffs had purchased video equipment from Bluff City Electronics, a Memphis-based store that is still in business today, for the express purpose of recording Ray being taken into custody. “They wanted to be sure there were no questions about whether he’d been read his rights, for example.”

But the discovery of the videotape came quite by accident. In 2011 Leatherwood — the keeper of records and archives for Shelby County, which includes the city of Memphis — was sifting through old materials from the Ray prosecution with his staff when they came across an obscure photo of a sheriff’s office employee using a video camera. It dawned on him that there might be footage of these proceedings somewhere, so he sent the photo to various city and county officials. The image found its way to Harvey Kennedy, Shelby County’s Chief Administrative Officer, who told Leatherwood that when he worked in the sheriff’s department he had seen a box with material marked “James Earl Ray” in a cabinet, which he simply put back.

“We got in touch with a person in the office of [Shelby County Chief Deputy] Bill Cash and asked him to look in the cabinet and he found it,” said Leatherwood. “I’ve tried tracking it back to see who put it in the credenza. As far as we can tell, it’s been sitting in the credenza of a sheriff’s department employee’s office.”

(MORE: TIME Looks Back: The Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.)

King was killed with a single shot at the Lorain Hotel on April 4, 1968, while visiting Memphis to support a sanitation workers’ strike. After the assassination Ray went on the lam, escaping first to Toronto, where he got a phony Canadian passport, then to London and finally Lisbon where he got a second fake passport. He returned to London and on June 8, as he tried to board a plane to Brussels at Heathrow airport, he was spotted and apprehended by a Scotland Yard official.

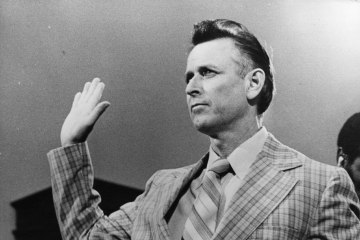

James Earl Ray, the convicted killer of Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King, taking the oath before a committee in Washington where he denied he shot Dr King.

On July 19, 1968, Ray was extradited to the United States to face charges. Sheriff Morris (who later served as mayor of Memphis and ran for Tennessee governor), wearing a suit and skinny tie, stepped onto the plane to meet the bespectacled and exhausted fugitive. On the the tape, he can be heard reading Ray his Miranda rights; he is then seen fitting the suspect with a bulletproof vest and finally delivering him to a jail cell in Memphis. Ray pleaded guilty and was eventually convicted of King’s murder. He was sentenced to 99 years imprisonment and died at Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary at age 70.

(AUDIO: The Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.)

Morris had reasons for wanting a video record of the arrest — mainly, to avoid a repeat of the shooting of President John F. Kennedy’s assassin Lee Harvey Oswald, a murder that prompted accusations of police mismanagement and launched a thousand conspiracy theories. Just two months after King was killed, Sirhan B. Sirhan assassinated Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles. So Morris flew to L.A. to see how the Sirhan arrest was handled. “No one wanted to have a Jack Ruby situation happen on their watch, so one of the things they did for Sirhan was to videotape it, so that’s where I believe the sheriffs got the idea,” Leatherwood says.

But mysteriously, the footage was shelved and forgotten for decades until the Shelby County staff discovered it. And even then, they had no way of knowing what was on the tapes since there was no machine available that could play its contents. Leatherwood said the county had sent out requests to video companies to find someone who could play the tapes. A New York-based company, DuArt, not only had the proper restoration facilities, but actually had an old Sony videotape machine of the kind used to record the original footage. “One of the tapes had a label that said ‘James Earl Ray Arrival on Plane,’ ” Leatherwood says. “Imagine seeing that label and knowing you can’t play them.”

Shelby County officials got the video back a few months ago, and made plans to release them around the time of the anniversary of King’s assassination. They are still working on getting much of the garbled audio cleared, Leatherwood says. The Shelby County Keeper of Deeds has already posted several clips to its website, including one explaining the process by which the new prisoner would be booked and processed upon arriving in Memphis: