Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel

Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel sketched out his plans for building a leaner Pentagon on Wednesday — and made some cogent observations on what needs to be done to square U.S. defense plans with U.S. fiscal reality — but he based his blueprints on a faulty foundation.

“Today America’s defense institutions are emerging, and in some cases recovering, from more than a decade of sustained conflict while confronting new strategic challenges – and doing so with significantly less resources than the department has had in the past,” he said in his first major policy address as defense secretary at the National Defense University in Washington.

“…significantly less resources than the department has had in the past…”?

That’s flat-out wrong, and a surprising statement coming from a defense secretary who served as a sergeant in Vietnam and knew balderdash, to put it politely, when he saw it.

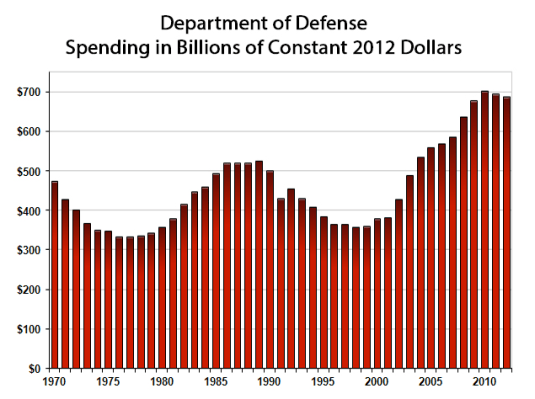

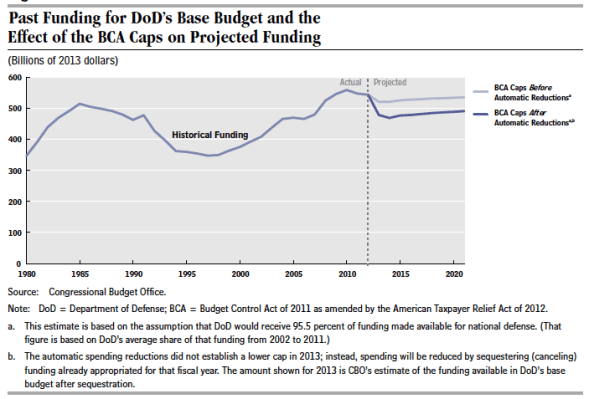

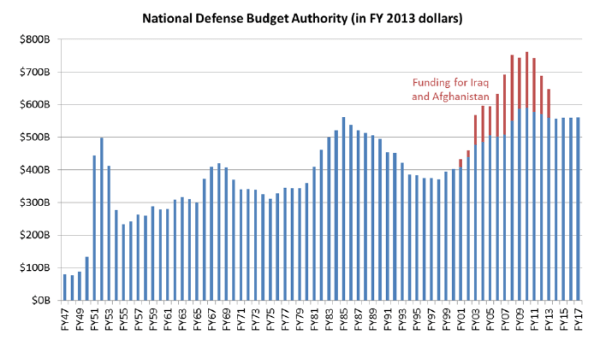

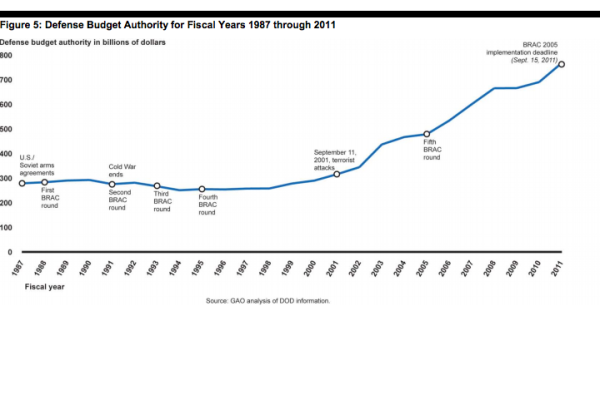

Review these charts and decide for yourself. They come from four different agencies — two governmental and two independent — and take historic looks at U.S. defense spending. Think of it as Where’s Waldo for defense dweebs — see if you can find where and when “significantly less resources” have been applied to the Pentagon:

What is true is that the projected rate of growth has been cut way back – and will keep being cut in the future if the nation’s political leaders fail to come to an agreement on a decade-long deficit-reduction package of $1.2 trillion. “All we’re doing is cutting the planned growth,” says Tom Christie, who served as the Pentagon’s top weapons tester from 2001 to 2005. “You can’t argue that the budget is significantly less than it was.”

The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office, in a report released last month, made clear the extent of the cuts the Defense Department faces:

In real terms, after the reduction in 2013, DoD’s base budget is about what it was in 2007, and is still 7% above the average funding since 1980.

That’s the true bottom line: the nation is spending more on its military than the Cold War average. But defense hawks like to measure military spending using a different yardstick: how much of the nation’s wealth are we pouring into the armed forces?

“A better way to gauge the `cost’ of defense is by measuring it as a percentage of the U.S. economy,” the American Enterprise Institute suggests. “In that respect, the economic burden of defense has been cut almost in half, from a 50-year Cold-War average of about 7 percent to 4.1 percent today (3.4 percent without war costs).”

Battleland has never understood the logic of linking military spending to the size of the U.S. economy, instead of the military threats facing the country. The nation should spend what is needed to defend the country without nailing it to some magic unrelated number (this also explains why Battleland will never go to work at a “think” thank).

“The speech is a real wet noodle,’ says Tom Donnelly, an AEI defense expert, “but it does prepare us for what’s to come “ in terms of additional cuts.

The speech “represents a bit of a turning point for the Pentagon, because he acknowledges that further cuts in defense spending are likely, if not inevitable, and that the Defense Department should begin preparing for them,” says Todd Harrison of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. “Secretary Panetta, in contrast, discounted that possibility and refused to plan for it.” (“We are dealing with a $41 billion shortfall” in the final seven months of the current fiscal year, “that was not planned for,” Hagel noted — in the passive voice that avoided pinning responsibility — during his Q&A session with the NDU audience.)

Yet so long as U.S. leaders bemoan cuts that haven’t happened, the nation will be locked in a spending death spiral of internal cost growth that corrodes fighting power by paying ever-increasing costs for each person in uniform and each weapon bought.

Donnelly’s colleague at AEI, Mackenzie Eaglen, agreed. “The defense build-down is here to stay,” she said. “Fundamental and structural reform is long overdue, and Secretary Hagel should be making the case for it regardless of whether the topline is going up or down. That will be the true test of his seriousness today.”

Hagel hinted at this in his speech:

In many respects, the biggest long-term fiscal challenge facing the Department is not the flat or declining top-line budget, it is the growing imbalance in where that money is being spent internally. Left unchecked, spiraling costs to sustain existing structures and institutions, provide benefits to personnel, and develop replacements for aging weapons platforms will eventually crowd out spending on procurement, operations and readiness – the budget categories that enable the military to be and stay prepared.

And procurement, he noted, is no piece of cake:

I am concerned that despite pruning many major procurement programs over the past four years, the military’s modernization strategy still depends on systems that are vastly more expensive and technologically risky than what was promised or budgeted for.

Beyond the claim of significant cuts, Hagel’s speech got some good reviews.

Arnold Punaro, a retired Marine major general and long-time staffer on the Senate Armed Services Committee, praised Hagel’s aim points. “He has zeroed in on the three sacred areas of acquisition, overhead, personnel and compensation that need significant reform both in the short and long term,” said Punaro, a critic of current Defense Department operations from his seat on the Pentagon’s own Defense Business Board. “I am sure there are those in the Pentagon if they could open their windows and jump they would — but clearly this is a breath of fresh air that hopefully will circulate throughout the Pentagon and the defense establishment.”

Gordon Adams, who oversaw Pentagon spending from the Office of Management and Budget during the Clinton Administration, also liked what he heard. “The approach to target is correct — resources constrain strategic choices — and the target selection hits a bulls eye – excessive acquisition costs, size and cost of personnel, and, above all, the big back office,” he said. “But like most puddings, the proof will be in the eating: will he discipline the appetites of the [four-star military service] chiefs?”

That’s the big question. Despite the efforts of the two prior defense secretaries – Robert Gates and Leon Panetta — to cut Pentagon fat, some of it is so well-marbled into the military’s meat that trimming it would challenge even the world’s best butcher. As Hagel put it:

Today the operational forces of the military – measured in battalions, ships, and aircraft wings – have shrunk dramatically since the Cold War. Yet the three- and four-star command and support structures sitting atop these smaller fighting forces have stayed intact, with minor exceptions, and in some cases they are actually increasing in size and rank.

Funny how that works. Defense secretaries come and go, but uniformed billets tend to hang around, and they preserve their fiefdoms as their civilian masters cycle in and out.

“Whoever Hagel’s listening to in the building is giving him bad advice,” former chief weapons-tester Christie says of his claim that the Pentagon will have to make do with “significantly less resources” than it has had in the past. “But that’s the tune that the military has been singing.”

On Wednesday, you might say, Hagel joined the chorus.