Unemployed veterans seeking work at a 2009 jobs fair in New York City.

The national commander of AMVETS was indignant. “The problem of veteran unemployment,” Cleve Geer told NBC News on Friday, “should be seen as a national disgrace.”

Just over a week earlier, Paul Rieckhoff, of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, had referred to an “unacceptably high veteran unemployment rate.” And the website of the House Veterans Affairs Committee now talks of “solving the veteran unemployment crisis.”

The problem with this shared narrative is that there is, in fact, no crisis. It’s an exaggeration, at best.

The reality is that veterans are more likely to be employed than non-veterans. This is indisputable.

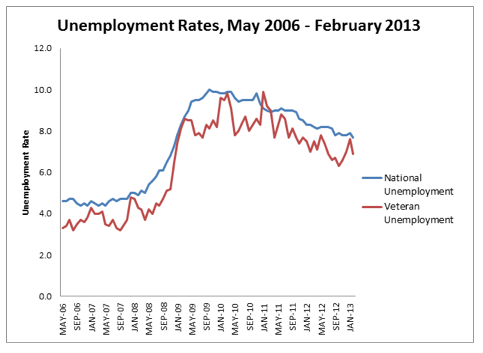

Historically, veterans have enjoyed higher rates of employment than the general public. Military service is such an advantage that, since 2006, the veteran unemployment rate has averaged a full percentage point below the national unemployment rate. As the chart demonstrates, veteran unemployment has been lower than the national rate in 79 of the last 82 months—while following roughly the same track.

Not only is the veteran unemployment rate lower than the national average, but perhaps even more significant is the fact that it’s trending distinctly downward—which is reflective of today’s recovering national economy.

By any empirical measure, there is no overall unemployment crisis among America’s veterans. They’re doing quite well—and better than their non-veteran peers.

Of course, that’s not the end of the story. To be certain, the employment situation for America’s newest veterans is more precarious. At 9.9% in 2012, the post-9/11 veteran unemployment rate still exceeds the national average. (Although it, too, is on the way down).

For many of us who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, this seems inexplicable. At least it did to me.

Armed with “down-range” management experience, I assumed I’d have little trouble finding work after completing a master’s degree in 2006.

Instead, I spent 11 months unemployed, trying desperately to hold on to my dignity. Medals—awarded for leading dozens of 101st Airborne Division soldiers in combat—sat in a drawer next to my bed, worth nothing as I sent out resume after resume.

As I tried to convince recruiters that I was qualified—that my experience mattered—my checking account ran dry.

Eventually, I was offered a short-term contract with a nonprofit. They offered me significantly less than I’d been making in the Army, but I was grateful and took it.

What I didn’t realize at the time—and what many don’t realize today—is that this difficult transition isn’t out of the ordinary for new veterans. To understand the reality of the situation, we have to get past the hyperbole in the media and look to what’s actually happening.

First, the unemployment rate among post-9/11 veterans is distributed unevenly. The elevated rate is driven largely by a single age group experiencing very high unemployment: those ages 18 to 24. For veterans in that age group, the average unemployment rate last year was 20.4%. In 2011, it was 30.2%.

By contrast, the rate among older Iraq and Afghanistan veterans is actually comparable to other veterans. For example, post-9/11 veterans between the ages of 45 and 54 have an unemployment rate of just 2.4%.

That’s why it’s so important to isolate the issue.

Of course, this raises the question: why is the unemployment rate for 18- to 24-year-old veterans so high?

Empirical data is limited, but common sense leads us to surmise that this is a demographic which recently left one job in search of, in many cases, a radically different career. It’s also a demographic with less education and civilian work experience. So it stands to reason that any such cohort would be immediately less employable.

If thousands of medical doctors suddenly quit practicing after four years and attempted to enter the job market in unrelated fields, how much luck would they initially have?

Thus, for many veterans whose skill sets don’t translate easily, making such a transition can require additional education, training, or both. And that takes time.

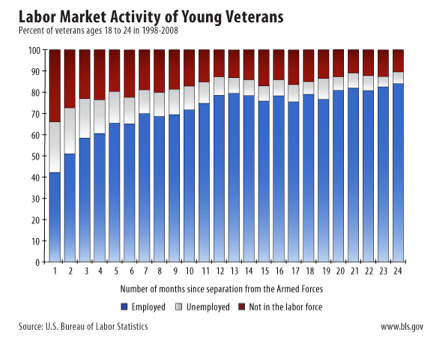

A single, often overlooked, chart explains the dynamic at work.

Using data compiled between 1998 and 2008, the chart illustrates that, among veterans ages 18 and 24, the average unemployment rate is highest immediately upon separation from the military. And that rate drops precipitously over the next two years.

For example, during the measured decade, veterans who were within one month of separation had an unemployment rate of nearly 24%. For those who’d been separated for at least a year, the rate dropped to 8.7%. And for those two years post-separation, the unemployment rate had fallen to 5.6%.

It’s a natural curve that veterans experience when they leave the military—which most do in their early 20s. They separate with few civilian qualifications, gain them over the course of several years, and then most find jobs within one or two years.

It’s not a crisis. It’s not “unacceptably high.” And it’s certainly not a “national disgrace”—especially given the state of the U.S. economy since 2008. It’s just a naturally rough re-entry.

So what should we be doing to make this re-entry as smooth as possible?

First, the rhetoric should be toned down. This is a manageable process, not a crisis—and it should be treated as such in the media.

Second, we need to better manage the expectations of separating service members. Rather than conditioning them to think they’re entitled to a job upon separation, regardless of their skill set—and rather than guilt-tripping companies into hiring them—we should shift to a more granular focus.

The current resource investment toward finding each veteran a job should be limited to those who are most qualified. When a veteran has an easily transferable job (like a logistics specialist), and that veteran wants to work immediately, then we should work to place that veteran immediately.

For those with less transferable skills (like artillerymen), we should stress training and education—not jobs. This should take place from initial entry through the active duty transition process.

Saying, as President Obama has, that “no veteran should have to fight for a job at home after they fight for our nation overseas” is well-intentioned. But it also creates a false sense of entitlement among inexperienced veterans which can work against the very companies who would hire them.

Infantrymen who’ve spent years learning to shoot and maneuver shouldn’t be surprised when they find themselves on a difficult, time-consuming route to civilian success. They have to accept that they’re behind their civilian peers professionally. In effect, it’s part of the sacrifice they signed up for in the first place. And we need to make sure that troops understand that up front—when they first enter the service.

Lastly, veteran and government organizations shouldn’t let up in their efforts to encourage businesses to hire qualified veterans. While many organizations go overboard in characterizing the employment situation, they are more often correct when they stick to fighting stigmas about post-traumatic stress—and convincing companies that veterans make great employees.

As callous as it may sound to some, we don’t owe all veterans jobs when they leave the service. What we owe every veteran is the education and training that will allow them to find jobs—whether it’s certification as an electrician or an electrical engineering degree through the Post-9/11 GI Bill.

When it comes to employment, being a veteran is a long-term advantage. We just need to ensure that everyone—to include troops, veterans, nonprofits, government agencies, and employers—understands that the road from Bagram to the board room is often challenging to navigate.

We should make it easier for veterans by helping them to navigate it with proper planning—and not with dire pronouncements or inflated expectations about the job market.

Brandon Friedman is a vice president at Fleishman-Hillard in Washington, D.C. and the author of The War I Always Wanted. From 2009 to 2012, he worked at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Follow him on Twitter at @BFriedmanDC.