A Marine with the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit takes part in a war game while training in the coastal mountains of Djibouti last fall.

Most Americans do not realize the extent to which the U.S. is becoming involved militarily in the welter of conflicts throughout Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa (check out the chaos here).

Although recent reports have tended to focus on the French intervention to kick Al Qaeda in Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) out in Mali — a effort that may now be devolving into a far more complex guerrilla war, that French operation is just one operation in what may be shaping up to be a 21st Century version of the 19th Century Scramble for the resources of Africa. It’s a policy that, from the U.S. point of view, is not unrelated to the pivot to China, given China‘s growing market and aid presence in Africa.

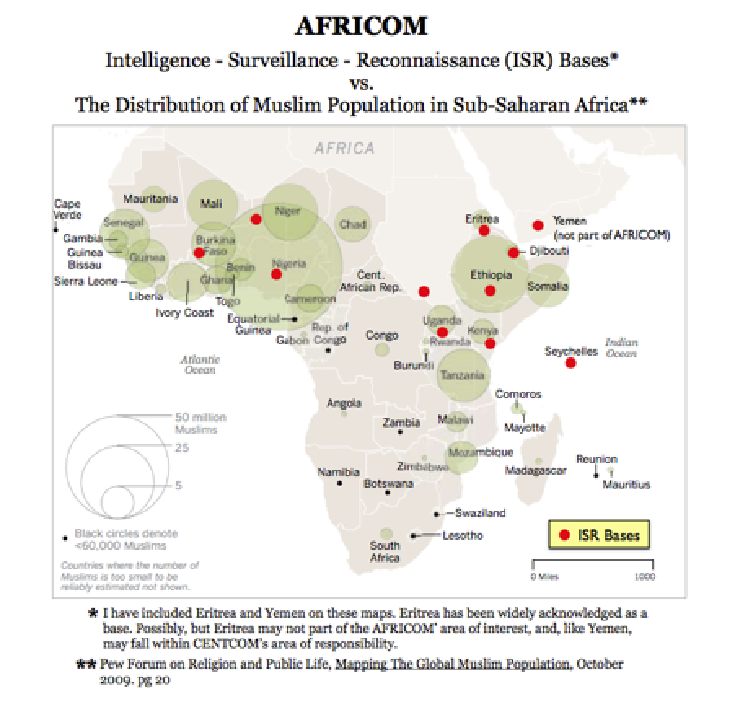

Last year, Craig Whitlock of the Washington Post provided a mosaic of glimpses into the widespread U.S. involvement in Africa in a series of excellent reports, including here, here and here. The map below is my rendering of the basing information in Whitlock’s report (and others), as well as the relationship between that basing information to distribution of Muslim populations in central Africa.

While the correlation between Muslim populations and our intervention activities will suggest different messages to different audiences, given our recent history, it is certain to further inflame our relationship with militant Islam.

Another sense of the metastasizing nature of our involvement in Africa can be teased out of the leaden, terrorist-centric, albeit carefully-constructed verbiage in the prepared answers submitted by Army General David M. Rodriguez to Senate Armed Services Committee in support of his 13 February 2013 confirmation to be the new commander of the U. S. Africa Command or Africom. I urge readers to at least skim this very revealing document.

The terrorist “threats” in sub-Saharan Africa that are evidently so tempting to the neo-imperialists at Africom do not exist in isolation. They are intimately connected to the ethnic/tribal discontent in Africa, a subject alluded to but not really analyzed by Rodriquez or his senatorial questioners in their carefully choreographed Q&A.

Many of these tensions, for example, are in part a legacy of artificial borders created by the European interventionists of the 19th century. These interventionists deliberately designed borders to mix up tribal, ethnic, and religious groups to facilitate “divide and rule” colonial policies. The 19th Century colonialists often deliberately exacerbated local animosities by placing minorities in politically and economically advantageous positions, thereby creating incentives for payback in the future. Stalin, incidentally, used the same strategy in the 1920s and 1930s to control the Muslim soviet republics in what was formerly know as the Turkestan region of Central Asia. In the USSR, the positioning of the artificial borders among these new “Stans” were widely known as Stalin’s “poison pills.”

The hostage crisis at the gas plant in eastern Algeria last January is a case in point to illustrate these deeply-rooted cultural complexities at the heart of many of these conflicts. Akbar Ahmed recently argued this point in one of his fascinating series of essays published by Aljazeera. This series, which I believe is very important, is based on his forthcoming book, The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a War on Tribal Islam, to be published in March by Brookings Institution Press.

Ambassador Akbar Ahmed is the former Pakistani high commissioner to the UK, and he now holds the the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at American University in Washington, D.C. The central thrust of his work is that discontent is widespread throughout the former colonial world, and is rooted in a complex history of oppressions of ethnic groups and in tribal rivalries throughout the region. This has created a welter of tensions between the weak central governments of the ex-colonial countries and their peripheral minority groups and tribes. He argues that these tensions have been exacerbated by our militaristic response to 9/11. He explains why military interventions by the U.S. and former European colonial powers will worsen the growing tension between central governments and these oppressed groups.

Among other things, Ahmed has laid out a devastating critique of U.S. grand strategy in its reaction to 9/11. By declaring a global war on terror and then conducting that war according to a grand strategy that assumed “You are either with us or against us,” the U.S. has not only created enemies faster than it can kill them, but in so doing, it has mindlessly exacerbated highly-volatile, incredibly-complex, deeply-rooted local conflicts. It has thereby destabilized huge swathes of Asia and Africa.

To wit, most readers of this essay will have heard of AQIM and probably the the Tuaregs as well. But how many of you have heard of the Kabyle Berbers and their history in Algeria? (I had not.) Yet according to Professor Ahmed, a Kabyle Berber founded AQIM, and that founding is deeply-rooted in their historical grievances. There is more to AQIM that that of simply being an al Qaeda copycat. You will not learn about any of this from Rodriquez’s answers, notwithstanding his repeated references to AQIM and Algeria; nor will you learn anything about this issue from the senators’ questions.

You can prove this to yourself.

Do a word search of General Rodriquez’s Q&A package��for any hint of an appreciation of the kind of complex history described by Ahmed in his Aljazeera essay, The Kabyle Berbers, AQIM, and the search for peace in Algeria. (You could try using search words like these, for example: AQIM, Berber, history, Tuareg, tribe, tribal conflict, culture, etc — or use your imagination). In addition to noting what is not discussed, note also how Rodriquez’s threat-centric context surrounding the words always pops up. Compare the sterility his construction to the richness of Ahmed’s analysis, and draw your own conclusions. Bear in mind AQIM is just one entry in Africom’s threat portfolio. What do we not know about the other entries?

As Robert Asprey showed in his classic 2000 year history of guerrilla wars, War in the Shadows, the most common error made by outside interveners in a guerrilla war is the temptation to allow their “arrogance of ignorance” to shape their military and political efforts.

Notwithstanding being reaffirmed in Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, it is beginning to look like Asprey’s timeless conclusion will be reaffirmed once again Africa.