Dr. Peter Linnerooth, right, on a cigar break with Army mental-health colleagues in Baghdad, 2007.

Dr. Peter Linnerooth spent nearly five years wearing an Army uniform, including the bloodiest 12 months in Iraq at the height of the surge. As a mental-health professional, his top mission was to keep troops from killing themselves. After he returned home, he spent another two years trying to save the vets he loved, working for the VA in California and Nevada.

Few who wore the uniform in the nation’s post-9/11 wars better understood the perverse alchemy that can change the rush and glory of combat into a darkening cloud of anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress. But strikingly, all that understanding — and the knowledge, education and firsthand experience that nurtured it — didn’t save Linnerooth.

“Pete struggled with PTSD and depression after his deployment to Iraq,” an Army comrade says. “Pete is a good example of how serving in combat can change someone. Pete was one of us,” he adds. “He’s the first Army psychologist that I know who killed himself.”

(MORE: Battling PTSD and TBI)

Linnerooth died in Mankato, Minn., on Jan. 2. He was 42.

He spoke eloquently in recent years about the need to care for the troops’ mental woes. He also warned of the grinding stress that providing such care inflicted on Army mental-health workers like him. He talked of it in the pages of TIME, and the New York Times. He was the lead author of a 2011 piece on such “professional burnout” among his peers who, like him, had gone off to witness the worst of war, day after day, patient after patient.

“Despite the resilience that may result from training and experience, it is reasonable to assume that professional burnout occurs at a relatively high rate among the vulnerable and overstretched population of clinical military psychologists,” Linnerooth wrote in an American Psychological Association journal. He was, eerily, telegraphing his own fate.

Linnerooth was a captain in the Army from 2003 to 2008. He served as the mental-health officer in charge of the 2nd Brigade Combat Team (Dagger), 1st Infantry Division (the Big Red One), in and around Baghdad from August 2006 to August 2007. The Army awarded him a Bronze Star for exemplary service at the end of the deployment.

(MORE: Study: 911 Dispatchers Experience PTSD Symptoms Too)

The Lives He Touched

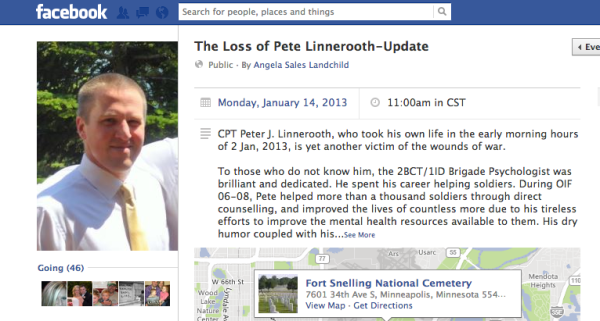

Word of Linnerooth’s death last week spread quickly among those with whom he had served, in Iraq and elsewhere. Dozens have posted memories on a Facebook memorial page. “Pete helped more than a thousand soldiers through direct counseling” in Iraq, said Angela Sales Landchild, whose Army medic husband served alongside him in Iraq. He “improved the lives of countless more due to his tireless efforts to improve the mental health resources available to them.”

“Heartbreaking,” posted Sarah Murray, wife of the brigade nurse. “I will never forget his contribution to the mental health of the brigade.”

“What a terrible loss and tragedy!” said Colonel Keith Sledd, Linnerooth’s battalion commander, from Afghanistan. “Pete was an outstanding person, Soldier, and doctor.”

“I don’t know how many times in my current counseling sessions I mentioned Pete the ‘Wizard,’ ” Army medic Jedidiah Ayers said. “We will never know how many lives he has saved through his caring.”

He achieved a lot. But it came at a high cost, personally and professionally. “He was really, really suffering,” his widow Melanie says. “And it didn’t matter than he was a mental-health professional, and it didn’t matter than I was mental-health professional — I couldn’t help him, and he couldn’t help himself.”

(VIDEO: Are Female Troops More Likely to Get PTSD?)

It seemed there was no one to help an Army hero who spent his career helping others. “The resources aren’t what they should be,” Melanie says. “The death toll for suicide is now higher than combat, and he was very frustrated by that.”

He shared those frustrations. Linnerooth told TIME three years ago that he first realized that Army mental-health workers were overwhelmed during a two-month stint at Fort Hood, Texas, two years before he went to Iraq. It was early 2004, and the first troops to deploy to Iraq had just started coming home with mental problems. “We were told you have to hold soldiers to a higher standard of severity and symptoms to diagnose PTSD,” he recalled being instructed. “Meanwhile, I’m looking at the DSM 4 [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition] — the standard of my profession — and saying ‘It doesn’t f—— say that here.’ ”

He said he was ordered to cut the standard 50-minute counseling sessions to 20 minutes. “You’d have to resist that,” Linnerooth said. But when he’d complain, the response was always the same: “This is a war,” he said his superiors told him.

The Army’s mental-health cadre, like other slices of the U.S. military, wasn’t prepared for a lengthy conflict. “You’re looking at 350 [clinical psychologists] to support the entire Army of about a half a million,” Linnerooth said in that 2010 conversation. “That’s way too little, and it’s led to way too much burnout.”

(MORE: Army Policy: Deferring Mental-Health Diagnoses in War Zones)

Marching Off to War

Then he went to Iraq. Once there, he said, he realized the situation was even more dire on the front lines. There was relentless pressure to get bodies into the fight. “When they tell you to make a soldier deployable, what are you going to do?” he recalled asking himself. “The Army has been criminally negligent — but I’m a captain — what am I going to say to a battalion commander who’s going to oppose my decision?”

He said he wasn’t alone. “When we were in Iraq, a chaplain, almost with tears in his eyes, said the Army is criminally negligent in its mental-health care of soldiers,” Linnerooth recalled. “And I believed that to be true as well.”

He was haunted by the procession of bodies, alive and dead, that he witnessed coming into the Riva Ridge Troop Medical Clinic. Even mental-health workers had to pitch in to help after mascals — mass-casualty events. The recollection of an explosion that ripped into four Iraqis — two grownups and two kids — especially tormented him. “The adults died quickly, but the kids didn’t give up,” Melanie recalls Pete telling her. “So they screamed in agony for hours until they finally died. Their skin was falling off, and the bone was showing through and there was nothing these guys could do for them except try to manage their pain while they died.”

Headed Home

Linnerooth, according to friends and colleagues, came back from Iraq a different man. After leaving the Army, he taught psychology for a year at Minnesota State University at Mankato, but found it dispiriting. “I was tired of 19-year-old college kids bitching to me about how hard I graded them,” he said, “when the 19-year-old soldiers that I was used to working with were hoping they would survive to see the next day.”

In 2009, the Minneapolis VA awarded him 100% disability for PTSD. It worked out to about $2,300 a month, tax-free. His 17-year marriage fell apart.

So he headed to the California coast in late 2009, near Santa Cruz. He moved across the street from his Iraq war buddy, Brock McNabb, who had worked alongside Linnerooth as a combat medic specializing in mental health. The pair worked for the VA, tending to mentally ailing vets at the Santa Cruz County Vet Center center in Capitola.

Given their work and their shared background, dark thoughts were routine. “We talked about suicide all the time,” McNabb says. “It is something that many vets are comfortable with talking about. Especially the two of us, since we dealt with suicidal ideation and completed suicides in our careers. He was not afraid of death, I think he was just afraid that he wasn’t going to mean as much as he did in the Army for the rest of his life.”

(MORE: The Army’s Continuing Dearth of Mental-Health Workers)

A Fresh Start

Then he fell in love with Melanie and decided to move to her place in Reno, Nev., and work for the VA there. His PTSD had ebbed while he was living alone in California, but it returned when he moved to Reno to live with Melanie and her two kids and had visits from his two children. “He had more control over his environment in Santa Cruz,” Melanie says.

Things did not go well at the Reno VA, where he had been hired to help vets afflicted with PTSD. For one thing, he was coming up on the two-year deadline to get a state psychologist’s license since being hired by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Battle buddies Brock McNabb, left, and Dr. Peter Linnerooth, working for the VA in California, 2010

“The Reno VA told him, ‘Don’t worry about it. Come on board even though you’re about to hit your two-year mark,’” McNabb recalls. Linnerooth’s VA bosses said the family-leave time he had taken while in California to spend time with his kids in Minnesota would extend the deadline, McNabb recalls. “But within a couple of weeks he was told by Reno’s human resources department, ‘Hey, we forgot to tell you, since you’re not licensed, we have to terminate you,’ ” McNabb says. “He was essentially fired.”

After that, his PTSD grew worse. The VA, McNabb said, denied his request to get help from a VA-funded private mental-health professional. “They wanted him to get treatment at the facility where he was supposed to work,” a second close friend says. “He just felt betrayed by the organization that was supposed to take care of him.”

McNabb recalls the Catch-22-iness of it all. “He was planning to go through a formal grievance process as a disabled veteran to get his job back,” McNabb says. “He said, ‘I obviously don’t want to see anyone there who I might end up working with in the future.’ ”

The VA said Jan. 14 it was “forced” to terminate Linnerooth after he failed to get the required license, but told him the agency would take him back once he got it. “To VA’s knowledge,” no one told him he’d get an extension because of the family leave he took, it added. “The Reno staff also says they did not limit his access to PTSD treatment,” the VA said. “They informed us they never would have done this.”

(MORE: Military Psychiatrists at War: True Life and Death Decisions)

Returning Home

As he spiraled deeper into PTSD, his second marriage began crumbling. He went to Oregon for a VA residential program, but it didn’t work out. So he headed back to Minnesota last summer. Melanie says that while the marriage was rocky, it wasn’t irrevocably broken. Pete visited her just before Christmas, and things went well. “He started getting some treatment and was becoming the person that I knew Pete was,” his widow says. “But he couldn’t quite get there fast enough.”

Yet Linnerooth kept trying. “He even started seeing a VA mental-health provider recently and thought it might go well,” McNabb says. But a combat veteran’s life can careen out of control in a flash. “More often than not, suicide is an impulsive act,” McNabb says, trying to explain what happened to his best friend. “It’s always a viable option in dealing with pain and loss. And it was for Pete.”

McNabb, now working for the VA in Hawaii, says his battle buddy found himself adrift, without a mission or even a job. “The only time that he felt that he truly mattered in his whole life wasn’t as the university professor or the VA counselor, but as the Army psychologist whose sole purpose in life was to help his soldiers get through just one more day,” McNabb recalls. “He once said, ‘See one more day past this one. That’s how you will make it through.’ I sure wish he did.”

His widow, who works for the VA in Reno, is profoundly frustrated by what happened. “We didn’t know,” she says, “how to get him the help that he needed.”

As is generally the case in suicides, there was no one cause. McNabb believes there were “many straws” involved. But the VA was part of it. “They could have given him more of a chance — all a person needs is that hope,” McNabb says. “Pete needed to feel like he still mattered. My God, he was a Bronze Star–winning Army psychologist. But the VA just looked at him as another psychologist who couldn’t get his licensure in two years.” McNabb knows about such things: he serves on a national VA special committee for PTSD.

But perhaps Linnerooth himself put it best in that 2010 chat with TIME. The military’s mission is to fight and win. “The Army is focused on the short term — ‘I need a warm body manning a gun in a Humvee,’ ” Linnerooth said. “That’s great — until that warm body is crazy and eats his gun.”

In the early morning hours of the second day of the new year, alone in his apartment, that’s just what Linnerooth did, after mixing Jack Daniels with Diet Coke with a telephone argument with his wife.

He will be buried at Fort Snelling National Cemetery in Minneapolis on 11 a.m. Monday.

He is survived by his widow, and three children — a son, 10, and a daughter, 6, from his first marriage, and a four-month-old son from his second — his mother, Gayle, and a sister, Mary Linnerooth Gonzalez. He is also survived, among the hundreds he treated for the PTSD that killed him, by an unknowable number – one? two? dozens? – of the grunts he loved, whose names are known but to God.

In His Own Words: Dr. Pete Linnerooth writes about a tough day at war. [link]

In His Own Words: Dr. Pete Linnerooth speaks to TIME in 2010: [audio http://nation.time.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2013/01/linnerooth.mp3]