The defense budget has become such a pampered darling of the American political system that the most stringent budget scenario that most Republicans and Democrats are currently contemplating — the so-called “Doomsday” scenario — is so stuffed with money as to be historically unprecedented.

Moreover, as Pentagon spending begins to approach the modestly-reduced levels it currently faces, we can anticipate a titanic effort by defense industry and many across the U.S. political spectrum to pump additional tens, even hundreds, of billions of dollars into Pentagon coffers.

Conventional wisdom on these questions is so poorly informed as to the actual data that politicians running for both the White House and Congress make stupendously daft statements about the defense budget, only to be greeted by many nods of pontificatory agreement.

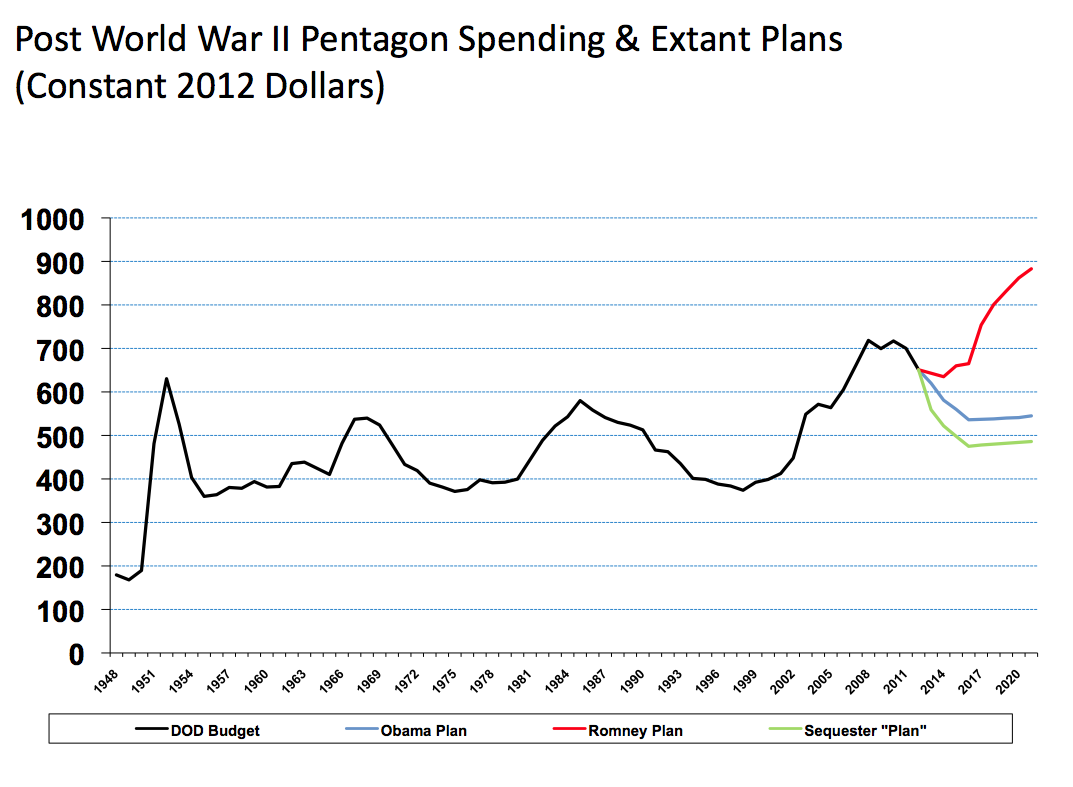

Consider the data in the graph below. It shows spending for the Department of Defense (DOD) since the end of World War II to 2022. The data up to the year 2012 are actual spending, expressed in inflation-adjusted dollars equivalent to the year 2012—according to DOD’s records. The data for the years 2012-2022 show Republican candidate Mitt Romney’s approximate plan (in red), President Obama’s (in blue), and the spending to be impose by “sequestration” (in green). That green line is a result of Congress’ failure to come to a broad budget deal under the provisions of the Budget Control Act of 2011, resulting in automatic reductions in DOD’s and other budgets now scheduled for January 2, 2013.

The spending amounts for the Romney plan assume his goal of 4% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for DOD is implemented gradually, as calculated by Travis Sharp at the Center for a New American Security. Compared to other calculations of Romney’s declared intent, it is one of the more modest calculations I have seen, even if Romney’s surrogates have tried to squirm—unsuccessfully—out of the actual commitment it involves in their effort to Etch-a-Sketch away his extreme positions from the Republican primaries.

The data for the Obama plan is from his 2013 10-year budget submitted by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) this year, and the data for the sequestration “plan” is from the Congressional Budget Office.

These data are for the Defense Department only and have been adjusted for inflation using OMB deflators. In each plan, money has been added to accommodate a rapid drawdown from the wars in Afghanistan and elsewhere.

Specifically, all three data lines assume the Obama budget request of $88.5 billion for 2013 for the wars and arbitrarily assume a drawdown to $50 billion in 2014 and $25 billion in 2015. No spending is added for the wars after 2015. In other words, the spending levels shown are about as low as the available data permit; however, by using nominal calculations for the drawdown from the wars, for inflation and for Romney’s declared intent, the data lines are also approximate.

Note how modest the “peace dividend” is when all war costs are done at the end of three years. In the Romney plan, there is virtually no dividend before the defense budget ramps sharply back up. The Obama plan does indeed veer downward, but it too resumes modest growth, as do the effects of sequestration.

Both the Obama plan and sequestration are remarkable when put into historic context: compare their low points to the aftermaths of the Korean and Vietnam Wars and the Reagan “spend up” in the 1980s: the lowest point of the lowest contemporary spending “plan” (the Doomsday scenario) is about $100 billion above any of the previous three low points.

Recall also, that two of those three previous low points were during the Cold War, when the U.S. faced hundreds of hostile divisions in Europe, when the U.S. Navy faced a Soviet navy that at one point numerically outnumbered it in both surface combatants and attack submarines, and when America was engaged in an international competition with the Soviet Union while simultaneously dealing with a dogmatically communist and fundamentally inimical Peoples’ Republic of China.

We had all throughout that period a far more existential and challenging threat to deal with than we do from al Qaeda and all its running dogs, who on their worst day can only do to us what the Soviet Union might consider a nuisance attack.

To the extent that there is a foreseeable threat that may require us to use conventional forces—if either Obama or Romney wants to test the patience of the American people for yet another misadventure in Syria, Iran or North Korea—those prospective enemies possess, altogether, defense budgets less than one-thirtieth that of the lowest point of what Leon Panetta has indelibly called a “Doomsday” budget.

There is no competent reason not to expect the post-Bush/Obama wars’ peace dividend to equate to those after the Korean and Vietnam wars; in fact, there is good reason to expect the dividend to exceed those of the Cold War periods.

Of course, with their blustering (Romney) and “pivot” (Obama) toward China, both candidates seek to justify historically very large (Obama) and gigantic (Romney) defense budgets. They squeeze off any notion of a peace dividend in an age when no state or group presents an existential threat to the United States and the largest non-U.S. regional power in the world (China) is also America’s second largest trading partner.

In fact, no one is currently planning any real peace dividend when the war in Afghanistan joins the war in Iraq as an unpleasant memory.

Not only is the projected peace dividend inappropriately modest; even that is not going to happen if some get their way. Defense corporations have tried to prompt the politicians into “saving” the defense budget with additional billions by threatening worker layoffs and massive lobbying efforts, and many politicians—from both parties—are bending heaven and earth to avert Panetta’s Doomsday scenario and to ensure U.S. defense spending never drops to that level.

For the first time in a long time, however, they are meeting some opposition. The Obama administration summoned the spine to scare off the Lockheed Corporation’s, and others’, attempt to send thousands of their own workers warnings of impending pink slips—conveniently timed to be immediately before the November 6 elections—unless the defense budget is pumped back up.

And—so far—some Democrats in Congress and the White House have insisted there will be no undoing of the automatic January 2 defense budget sequester unless and until the Republicans back off of their relentless protection of low rates for high income tax payers.

What is particularly remarkable is that the Democrats have held their ground on these now-linked issues, even enduring the Republican slings and arrows of “devastating” and “arbitrary” defense budget cuts in an election season. Notorious for their pre-emptive capitulation in the face of such attacks in the past, the Democrats have not performed their usual cower in the bushes, waving instantly higher defense budgets through. At least not yet.

All of this, of course, is mere prologue to the post-election period.

Republicans and other self-declared defenders of the defense budget are pushing hard for a “compromise” of delaying the sequester, effectively taking it off the table as a bargaining chip to trade against tax cuts, or not, for the rich.

The broader budget negotiations will move on to address not just those tax rates (de-linked from defense), but entitlements and the entire federal budget and fiscal construct.

If the sequester-delaying “compromise” is accepted, the idea of any meaningful peace dividend as the Afghanistan war draws down can be forgotten. The sequester, let alone any future defense spending levels below it, will be off the negotiating table as Republicans and Democrats make whatever deal they are able to with defense as essentially a sideline issue, rather than linked directly to other core issues, such as tax rates.

The budget negotiations that inevitably must occur after the elections, whether they are conducted by President Obama or President-elect Romney, and whether they occur during the lame-duck session of Congress immediately after the elections or later in the winter, will be an acid test of the U.S. political system.

During a period of a historic opportunity for a peace dividend in the absence of an ongoing war or any credible overwhelming threat, it horrifies big defense-spending advocates that the over-pampered object of their political affectations is paired with taxes as issues to be resolved; they fear it for the simple reason that many of their major political allies value the tax issue at the same level, or higher, as defense spending.

Those big defense spenders want to break that linkage, precisely what their seemingly innocuous proposal to delay the defense sequester would do.

The future course of defense spending is at stake. The size of the peace dividend will vary from virtually nothing to a historically appropriate level. Which path the nation takes will shift hundreds of billions of dollars between guns and butter.