U.S. Army troops secure a landing zone for helicopters during a war game in South Korea.

Part Three of Five

The U.S. may have global power and responsibilities, but in recent years, a strategic shift has occurred. China’s military has risen in conjunction with its driving economy, which has prompted a refocus on Asia and a “pivot” or “rebalance” in American grand strategy.

Thus, while we explored in our two previous pieces the drivers of sequestration and what it might do to the U.S. defense budget in comparison to world military spending, that would miss a major part of the story. One should also put U.S. military spending not just a global context, but a regional one.

(MORE: Comparing Defense Budgets, Apples to Apples)

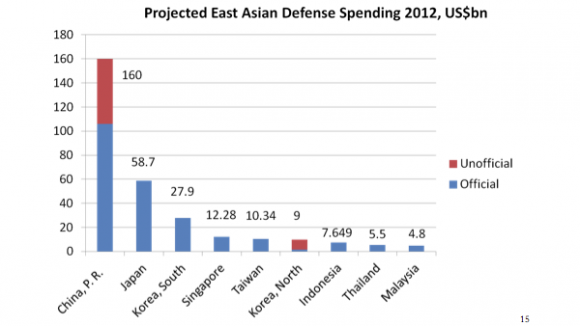

Within Asia, China is a dominant defense spender, both in its official budget and its more realistic overall unofficial budget. North Korea, which we’ll look at in more detail in the next part, equally has a disconnect between its official budget of $1 billion and the more likely estimates of $9 billion.

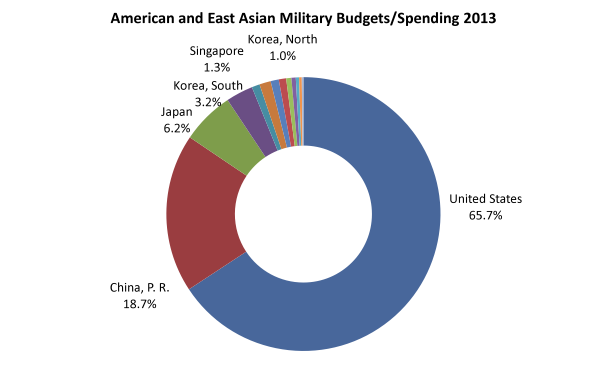

However, here again, the numbers take on a far different interpretation when you include the true Asian superpower, the United States, in the context.

If sequestration were to occur, the U.S. slice of the pie goes down, but is still a dominant slice, even more so if one includes its allies in the weighting.

Of course, the U.S. has global responsibilities, and so these figures should not be taken as the end of the story. Akin to the German naval position versus the British prior to World War I, a rising regional power like China might present a larger threat than any straight comparison of their relative numbers. A global power like the British back then or the U.S. today can be spread too thin, while the regional power’s resources are all focused (so the British during this period used variations on the “two-power standard” as their guide to naval force size, ensuring a fleet larger than the two next powers combined). Of course, in turn, the global power can still bring these other resources to bear in regional scenarios whenever the situation grows important, and that regional power is also counterbalanced by the other allies within the region, who sees its growth as a threat.

Military spending as compared to GDP shows similar weights. Other than North Korea, which has the dark combination of being a garrison state with a withered economy, the US percentages still rank high regardless of the scenario. Even in the worst scenario of sequestration, the US is still at 3.45% of GDP, a full point higher than China at 2.36% of its smaller but rapidly growing economy.

Part 4: A closer look at the Korean peninsula

Part 1: A sequestration primer

Part 2: Comparing defense budgets, apples to apples

Part 3: A case study: east Asia

Part 4: Impact on the Korean peninsula

Part 5: Stupid, but not disastrous

Peter W. Singer is director of the 21st Century Defense Initiative at Brookings. Check here for the full list of source material for this series of articles.

MORE: Sequestration and What It Would Do to U.S. Military Power