Former Taliban fighters surrender their rifles to the Afghan government in the central province of Ghor as part of a U.S.-funded reintegration program.

Winning a war can be tricky business, especially if you’re a U.S. soldier outfitted with the U.S. military’s formal guide for reintegrating the Taliban into a peaceful Afghan society. This is is different from the money the Pentagon is spending as part of the Commander’s Emergency Response Program (CERP), which we wrote about in May.

You really need to get down into the fine print of Money As A Weapon System-Afghanistan (MAAWS-A) Afghanistan Reintegration Program (ARP) to see what’s allowed and what’s not. And even then it’s not completely clear.

For example, the “purpose” of the Afghanistan Reintegration Program (on page 4) is to spend money

…to stabilize local areas by convincing insurgents, their leaders and their supporters to cease active and/or passive support for the insurgency and to become peaceful members of Afghan society.

…but U.S. troops are barred from spending such funds (per page 15)

…solely as a payment to stop fighting against GIRoA [Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan] U.S. and/or Coalition Forces.

Wow. The use of the word “solely” there opens up a hole big enough to drive a VBIED – more commonly known as a car bomb – through.

The guidelines say money can be spent on projects “designed to remove the legacy of conflict through the clean-up, repair, and reconstruction of their war-damaged communities, in order to support the transition to sustainable peace.”

As you pore through the manual, you are impressed with its breadth, but left wondering how workable it is. Some highlights (h/t Public Intelligence):

— Reintegration programs are Afghan led programs that have the outward appearance of an Afghan driven program consistent with the Afghan constitution and the Afghanistan Peace and Reintegration Program (APRP)

— Reintegration efforts should benefit and be provided to peaceful members of a community as well, not just reintegrees, in order to avoid perverse incentives. For example, measures should be taken to ensure peaceful members of a community are able to partake in the dividends of the peace process in order to avoid resentment of reintegree’s who are also benefiting from the reintegration program.

— Vetting is the process by which potential reintegrees are assessed as to whether they will be accepted back into the community. Vetting will be conducted at the community level by local elders and/or village leaders, in coordination with Ministry of Interior (MOI) and National Directorate of Security (NDS). All reintegrees seeking reintegration will have their biometric and identifying data collected by MOI and submitted to the Afghan National Security Force (ANSF), ISAF and UN databases to run background checks and create a record in order to prevent more than one attempt at reintegration.

— The use of reintegration funding is authorized to cover food and refreshment costs for either a ribbon cutting ceremony or conference (shura) when directly related to an approved reintegration project. Food and refreshment costs should be limited to $500 per ceremony/conference; however, in rare cases where the number of attendees will make it difficult to stay within this threshold, a $10 limit per attendee is authorized. In such cases, a memorandum signed by an O-6 U.S. commander will be uploaded in CIDNE upon completion of the event documenting the number of attendees and total value spent on food and refreshments.

— The use of reintegration funding is authorized to cover travel expenses, “fuel costs only,” for individuals specifically invited to attend the conference by a Provincial or District Governor…Expense is limited to $100 per person.

— It is authorized to provide temporary/limited support (transportation, meals, lodging, and incidentals), for a period not to exceed 7 days, to potential reintegrees who have come forward with interest in reintegration, but have not initially committed themselves to renouncing ties to the insurgency. If after 7 days the potential reintegree is not fully committed to renouncing the insurgency, all reintegration support must cease.

— To avoid recidivism for the special cases in which a reintegree is no longer welcome within the community, funding may be required for relocation, temporary support for training, education and initial living expenses so the reintegree can resume a peaceful and productive life. These cases may include reintegrees who have been detained and released from a U.S. or GIRoA detention and correction facility. Support may include resettlement and initial living expenses for the reintegree and immediate family members.

— Materials, tools, and the labor associated with erecting protective security equipment, to include, barriers, walls, guard towers, community fence lines and other physical protective measures to provide protection for reintegrees and/or approved reintegration programs is authorized.

— Ribbon Cutting Ceremony: It should be emphasized that a core element of the reintegration program is the need to link the people of a community to their government so they can see, trust, and respect the government. In many cases, ARP projects can be powerful vehicles to reinforce this link, especially when project implementation is coordinated closely with GIRoA sub-national and/or national representatives. Keep in mind that ribbon cutting ceremonies should not highlight the fact that ARP projects are funded by international donors. Such emphasis may undermine GIRoA’s legitimacy. Instead, commanders should maximize the COIN/Reintegration intent and make every effort to show that events are GIRoA led. Ribbon cutting ceremonies are not discouraged, rather it is emphasized that commanders use their discretion and understanding of COIN/Reintegration intent to best make use of these opportunities.

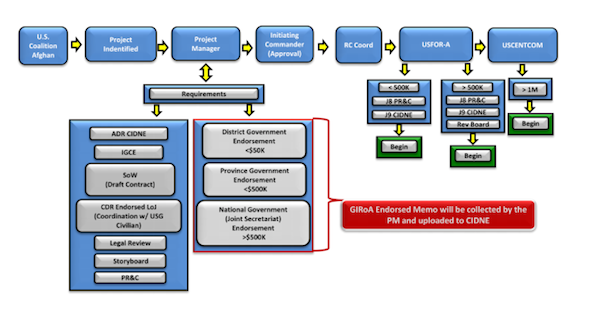

Here’s a helpful flow chart showing how these kinds of projects get off the ground:

dod

Then there’s this alternative approach to weaning Afghan villages from the Taliban. “Billions of dollars in aid money have been spent on Afghanistan, and there is virtually nothing to show for it,” writes G. Scott Alamanach Mikalauskis, who spent three years as a civilian contractor in Afghanistan and Iraq, in Small Wars Journal. “The conventional approach taken by most aid programs has been a counterproductive disaster, and it will be shown that a better implementation strategy is capable of wresting whole communities from Taliban control.”