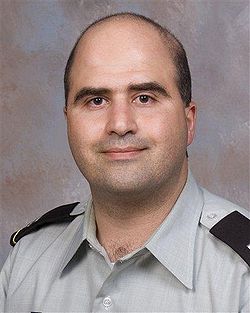

Major Nidal Hasan

When the world first learned the identity of the alleged attacker in the deadly shooting rampage at a Texas army base in November, 2009, the photograph seen around the world was of a clean-shaven, Major Nidal Hasan, smiling broadly and dressed in a crisp, neat U.S. Army uniform. The latest image of the Army psychiatrist, who is facing the death penalty for allegedly killing 13 and wounding 32 individuals, is of a grim-faced man, wearing an orange jail jumpsuit, and sporting a bushy beard — a beard that has become a point of legal contention and courtroom wrangling.

Hasan’s insistence on wearing a beard — a violation of military rules, but, according to his legal team, an expression of his Muslim faith — has caused conflict in the military courtroom at Ft. Hood in central Texas, site of both the shootings and the upcoming trial. Now, the presiding judge, Col. Gregory Gross, who has already ordered the defendant to shave, has said if the major does not cut off his beard, he will order Hasan be forcibly shaved, as permitted under U.S. Army regulations, before the trial begins in three weeks.

(PHOTOS: The Troubled Journey of Major Hasan)

Hasan first appeared in military court sporting the beard in June and despite repeated orders by the Gross, the major has refused to comply with U.S. Army uniform and appearance regulations that forbid beards. His defense counsel told the judge the beard is an expression of his religious conviction and should be allowed as such, but Gross has overruled their arguments and ordered Hasan out of the courtroom until he complies with army regulations. Gross allowed Hasan to watch the pre-trial proceedings from a nearby trailer. But when the trial begins on August 20, excluding Hasan from the courtroom could put the case in some legal jeopardy, opening the door for an appeal if the major is convicted. Col. Gross expressed that concern when he found Hasan in contempt of court last week, fining him $1,000 and once again ordered him to shave.

Ordering Hasan to watch the trial from outside the courtroom would be a risk, according to Eugene R. Fiddell, who teaches military law at Yale Law School. “A sanction like that is very strong medicine,” Fiddell says, “and I think the judge would be tempting fate if he used (the beard) as a reason for excluding the accused.”

The ruling was not incorrect under the law, but perhaps the judge should have shown more flexibility, Fiddell suggests. Duke University law professor Scott L. Silliman says Col. Gross was correct in his ruling and should hold to it. Silliman, director emeritus of Duke’s Center on Law, Ethics and National Security, adds: “Hasan is still in the Army and must comply with dress regulations.” A 1986 U.S. Supreme Court opinion, Silliman says, upheld the authority of a military judge to order defendants to comply with military uniform and appearance regulations during court martials.

The US Army has on a few, “very rare” occasions allowed soldiers to wear beards, Silliman says. None of the exceptions involved soldiers facing court martial. Two Sikh medical officers and a Muslim intern at Walter Reed Army Medical Center were granted exemptions in 2009, and a fourth enlisted man, a Sikh with language skills deemed necessary to the Army, also was given a waiver in 2010, according to the Army Times. Some African-American soldiers have been granted medical permission to forego shaving as they battle so-called “razor bumps” or pseudofolliculitis barbae, but they are limited to very short facial hair, around one-eighth of an inch.

As Fiddell points out, military traditions have changed over the years. General Ulyssess S. Grant and other 19th century military leaders with their generous, even bombastic facial hair would be out of compliance with modern rules and regulations. But the emphasis in modern times has been on the clean-shaven look, in part, the military says, to help with the fit of hi-tech equipment and gas masks. In September of 2002, U.S. Special Forces troops in Afghanistan who had gone native with long beards and indigenous clothing were ordered to abandon the local look and go back to military-style grooming. The order caused some grumbling since soldiers felt it helped them establish rapport with the locals who regard a beard as a sign of manliness, according to the New York Times.

As for Hasan’s insistence that the beard is an expression of his religious piety, Muslims scholars hold a variety of opinions about the necessity to grow a beard and how to maintain it. In June 2010, it was reported that Hizbul-Islam militants in Somalia were ordering the men of Mogadishu to grow beards or face consequences. Various Islamic scholars told the BBC that views vary about the wearing of beards. “In my opinion, this is a bit like the issue of women wearing headscarves. It is not one of the compulsory pillars of Islam, like prayer or fasting,” Imam Dr. Abduljalil Salid, a member of the Muslim Council of Britain, told the BBC.

Outside of radical and conservative circles, most contemporary Muslim scholars do not emphasize the beard as an important expression of spirituality, according to David Bryan Cook, who teaches at Rice University on the origins and historical development of Islam. That fact is obvious, Cook says, to anyone who travels the Muslim world and sees legions of clean-shaven men at every turn. But for radicals and many Islamists, Cook says, it is a “point of pride” to flaunt an impressive beard. For example, Khalid Sheikh Muhammed, the so-called mastermind of the September 11, 2001 attacks, Cook says, was relatively clean-shaven at his capture but, under detention, grew an “impressive beard.”

Beards have come to be viewed as shorthand symbols of the wearer’s affinity for conservative Islamic values, both religious and political. Following the fall of President Hosni Mubarak and the political ascent of Islamist parties, Egyptian police officers and flight attendants are challenging regulations that ban beards. It has been headline news in Egypt that, for the first time in modern history, both the president and prime minister sport beards. In a recent editorial dubbed “Two beards too much,” — the headline inspired by a tweet — Al-Arabiya.net Deputy Editor-in-Chief Farrag Ismail suggested Egypt was going through a “bearded stage.” He acknowledged some observers thought the ascent of the two bearded leaders might portend the establishment of a religious state, but added the “two beards too much” phenomenon is “not as dangerous as many want them to seem, if we bear in mind that religiosity is a personal matter that has nothing to do with professional performance and the ability to run the country efficiently.”

The U.S. Army insists its rules about facial hair have nothing to do with religion,but reflect the necessity for discipline and order, also key to the court martial process. Silliman says the judge should resist any pressure to relent and allow Hasan to disrupt that order. “It would set a bad pecedent,” he says. But Fiddell says the jury would “take it in stride” if Hasan appeared unshaven or our of uniform. “An accused who refuses to come into court clear-shaven in any kind of trial, be it military or civilian, is not threatening the orderly process of the proceedings,” Fiddell says.

“I think the judge would be well-advised to put up with it and let the chips fall where they may, in terms of the reaction of the members of the jury,” Fiddell says. Hasan’s jury will be made up of fellow officers sharing his rank of major and above. Hasan’s insistence on the beard, however, may be a glimpse of what is ahead as the trial gets underway. “What this tells me,” Fiddell says, “is this trial is likely to involve quite a bit of theatrics if Dr. Hasan is this far off the reservation.”

It has been almost three years since since the Nov. 5, 2009 shooting in a military staging area for troops heading to Afghanistan. The trial has been delayed somewhat, Silliman says, by Maj. Hasan’s medical treatment — he remains paralyzed from a gunshot wound — and some legal maneuvering, plus a change of counsel has slowed the normally brisk military law process. But given the weightiness of the case, the length of time it is taking is understandable, Silliman says, and he notes that the appeals process, if Hasan is found guilty, will be a lengthy one as well. (The major’s legal representation will be provided for him free of charge as part of his military benefits.) After any appeals within the military’s appellate system, pleas could be made to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Services, made up of five civilian judges appointed for 15 year terms by the President. Beyond that, appeals could go to the U.S. Supreme Court and, of course, to the President for clemency since he or she must sign the death warrant. No one has been executed under the Uniform Code of Military Justice since 1961.

Whether Hasan appears in court at his next appearance with or without the beard, the trial is sure to receive attention around the world. “The other side, so to speak, is going to capitalize on this case,” Fiddell says. “Some people are going to view Dr. Hasan as a hero whether he is clean-shaven or not. It will make for additional bad press if he resists being shaved and is physically restrained…I would have advised the judge against the ruling.”