Financed by the Pentagon and produced by the Institute of Medicine, (that influential member of the National Academy of Sciences with particular political and legislative sway), a 400-page report published Friday recommended a broad range of PTSD-related initiatives. They include annual PTSD screenings for troops returning from combat, and a more coordinated approach to supporting those with PTSD between the Department of Defense and the Veterans Administration.

Financed by the Pentagon and produced by the Institute of Medicine, (that influential member of the National Academy of Sciences with particular political and legislative sway), a 400-page report published Friday recommended a broad range of PTSD-related initiatives. They include annual PTSD screenings for troops returning from combat, and a more coordinated approach to supporting those with PTSD between the Department of Defense and the Veterans Administration.

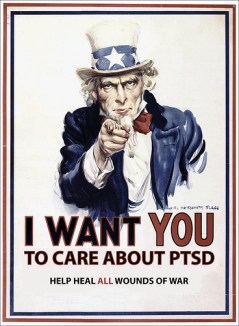

Two factors addressed in the study are cause for concern: first off, while 20% of our returning veterans are diagnosed with PTSD, barely half of them actually receive treatment; secondly, for those that do receive treatment, the DoD and the VA aren’t adequately tracking the success of their respective treatment programs. Why is it that so few of our men and women who return home suffering from PTSD actually seek treatment? One word: stigma.

Despite the efforts by leaders up and down the hierarchy within the DoD and the VA to reduce the stigma of seeking mental health counseling, there remains a stark perception amongst much of our veteran and non-veteran population that seeking mental health services is a sign of weakness and dishonor. Many active duty personnel refrain from seeking help out of an acute fear of potential repercussions from their command, and a strong desire not to become labeled as a “head case” by their peers.

Initiatives such as annual PTSD screenings sound great on paper, but until the mindset changes and the stigma of mental health counseling fades away, these annual screenings will follow what’s referred to in the finance realm as “Garbage In, Garbage Out.” In other words, if stigma prevents service members from being honest on their PTSD screening questionnaires, then any conclusions drawn from those surveys will be fundamentally flawed, at best.

What’s also troubling is the fact that between the DoD and the VA, there are a wide array of programs that have been developed for treating PTSD. But there is a lack of consistency with how these programs are implemented by the organizations. There is also, according to the report, surprisingly little information regarding the newer, so-called innovative treatments such as yoga and acupuncture, and whether any of these treatments are actually effective in the long run.

On a positive note, the cornerstone treatment programs developed by the VA and supported by robust data, Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) and Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE), are cited as successful treatments for PTSD. In order to effectively lesson PTSD symptoms, each program requires months of weekly appointments (and a great deal of sometimes excruciating homework for the veteran to complete between appointments). In other words, the treatments that have been proven effective require a significant commitment of time, energy, and fortitude on the part of the veteran and the VA alike.

Recovering from (and treating) PTSD is hard work, period.

Let’s hope that the VA is able to marshal the money and the psychologists necessary to treat the flood of veterans seeking shelter from PTSD. In the meantime, let us work to remove the barriers to getting help, namely stigma, so more veterans suffering with PTSD will actually seek the help they so desperately need — and deserve.