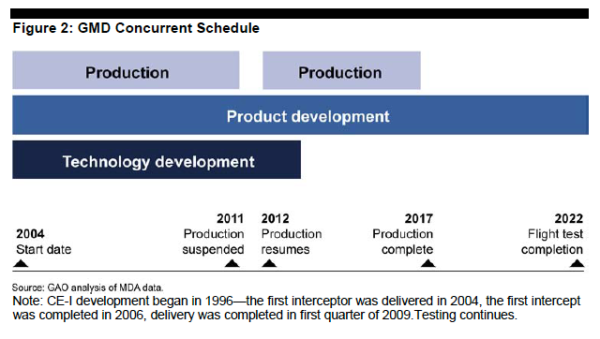

This simple graphic, from a Government Accountability Office report released Friday, shows how weapons should be developed:

After all, it makes sense: you don’t start building something until you’ve developed the technology it needs to work. Then you develop the weapon. Only after those two steps do you begin bending metal, as they say, and start building your tactical-nuclear widget, or whatever it is. But that makes far too much sense for the U.S. military.

After all, it makes sense: you don’t start building something until you’ve developed the technology it needs to work. Then you develop the weapon. Only after those two steps do you begin bending metal, as they say, and start building your tactical-nuclear widget, or whatever it is. But that makes far too much sense for the U.S. military.

The Pentagon seems to have a reflexive need to exaggerate the threats facing the nation, so it can engage in what is called concurrency – developing and building a weapon at the same time.

This made no sense – none, zip, nada – for the $400 billion F-35 fighter program, which is now plagued with problems, schedule delays and cost overruns because the military has rushed it into production before its blueprints were final. There is no one else in the world with the quantity and quality of so-called 4th-generation fighters possessed by the U.S. military, but that edge is deemed insufficient.

The 5th-generation F-35 is vital to avoid threatening air defenses and surface-to-air missiles increasingly fielded by potential adversaries, advocates say. Skeptics would simply note that national defense is a question of assessing risk, and over-estimating that risk – as the U.S. military (and certain politicians) have done since World War II – is part of today’s U.S.-national security DNA.

Which brings us back to that GAO chart on the best way to develop a new weapon. Here’s how the key part of the nation’s missile defense shield has been developed:

The Pentagon did this under orders from President George W. Bush, the GAO says:

[The Pentagon’s Missile Defense Agency] undertook a highly concurrent acquisition strategy to meet the President’s 2002 directive to deploy an initial set of missile defense capabilities by 2004. To do so, the [Ground-based Missile Defense] element concurrently matured technology, designed the system, tested the design, and produced and fielded a system. While this approach allowed GMD to rapidly field a limited defense that consisted of five…interceptors and a fire control system, the concurrency resulted in unexpected cost increases, schedule delays, test problems, and performance shortfalls. Since then, MDA has produced and emplaced all of its planned…interceptors. To address issues with the…interceptors, MDA has undertaken an extensive retrofit and refurbishment program.

But no sooner had the Pentagon begun deploying this first-generation missile interceptor than it decided to upgrade it:

Prior to MDA fully completing development and demonstrating the capability of the initial interceptor, MDA committed in 2004 to another highly concurrent development, production, and fielding strategy for an enhanced version of the interceptor—CE-II…MDA proceeded to concurrently develop, manufacture, and deliver 12 of these interceptors before halting manufacture of components and delivery of interceptors in 2011 due to the failure in [Flight Test GMD]-06a. Although MDA had not successfully tested this interceptor, failing in both its attempts, it manufactured and delivered 12 of these interceptors.

The discovery of the design problem while production is under way has increased MDA costs, led to a production break, may require retrofit of fielded equipment, delayed delivery of capability to the war-fighter, and altered the flight test plan. For example, the flight testing cost to confirm the CE-II capability has increased from $236 million to about $1 billion.

In addition, the program will have to undertake another retrofit program, for the 10 CE-II interceptors that have already been manufactured. According to a GMD program official, although the full cost is currently unknown, he expects the cost to retrofit the CE-II interceptors to be around $18 million each or about $180 million for all 10. Intended to be ready for operational use in fiscal year 2009, it will now be at least fiscal year 2013 before the warfighter will have the information needed to determine whether to declare the variant operational.

The GMD flight test program has been disrupted by the two back to back failures. For example, MDA has restructured the planned multiyear flight test program in order to test the new design prior to an intercept attempt. MDA currently plans to test the new design in a nonintercept test in fiscal year 2012.

Because MDA prematurely committed to production before the results of testing were available, it has had to take steps to mitigate the resulting production break, such as accelerating retrofits to 5 of the CE-I interceptors. Program officials have stated that if the test confirms that the cause of the failure has been resolved, the program will restart the manufacturing and integration of the CE-II interceptors. According to MDA, because of the steps taken to develop and confirm the design change, a restart of the CE-II production line at that time will be low risk. However, while MDA has established a rigorous test plan to confirm that the design problem has been overcome, the confirmation that the design works as intended through all phases of flight, including the actual intercept, will not occur until an intercept test—FTG-06b—currently scheduled for the end of fiscal year 2012 or the beginning of fiscal year 2013.

High levels of concurrency will continue for the GMD program even if the next two flight tests are successful. GMD will continue its developmental flight testing until at least 2022, well after production of the interceptors are scheduled to be completed. MDA is accepting the risk that these developmental flight tests may discover issues that require costly design changes and retrofit programs to resolve. As we previously reported, to date all GMD flight tests have revealed issues that led to either a hardware or software change to the ground-based interceptors.

Did you catch that sentence?

GMD will continue its developmental flight testing until at least 2022, well after production of the interceptors are scheduled to be completed.

Iran and North Korea – neither of whom is anywhere close to being able to threaten the U.S. with a missile force worthy of this kind of defense – must be delighted. U.S. taxpayers, not so much. Just think – by the time Tehran and Pyongyang might be able to threaten us, we’ll have to launch a new missile-defense system to deal with the threat, because today’s will be decrepit.