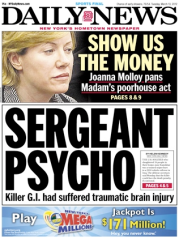

For the past few days, Washington’s, America’s, probably much of the world’s airways have been filled with commentary about the horrific killings in Afghanistan allegedly committed by an American soldier. Radio, TV and the blogosphere have been inundated with reports, predictions, and speculation—why he did it, what it means for the American war effort in Afghanistan and what it means for the future of the military. The New York Daily News featured the headline “Sergeant Psycho.” Other, less inflammatory and ridiculous story headers have appeared across the spectrum of platforms, prompting a backlash of stories denouncing the press stereotype of returning veterans as ticking time bombs of psychoses. No sane person would commit such an act. So it seems safe to assume that there is some sort of mental health issue—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) or something considerably worse—at play. But the rush to judgment by the pontificating classes has been disturbing.

For the past few days, Washington’s, America’s, probably much of the world’s airways have been filled with commentary about the horrific killings in Afghanistan allegedly committed by an American soldier. Radio, TV and the blogosphere have been inundated with reports, predictions, and speculation—why he did it, what it means for the American war effort in Afghanistan and what it means for the future of the military. The New York Daily News featured the headline “Sergeant Psycho.” Other, less inflammatory and ridiculous story headers have appeared across the spectrum of platforms, prompting a backlash of stories denouncing the press stereotype of returning veterans as ticking time bombs of psychoses. No sane person would commit such an act. So it seems safe to assume that there is some sort of mental health issue—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) or something considerably worse—at play. But the rush to judgment by the pontificating classes has been disturbing.

I don’t think anyone could catch every panel of experts pulled together to opine on this subject, but I’ve made a point to watch and listen to many of them. And one thing in particular struck me about the ones I’ve watched and listened to: none of them included a soldier who has come through the war with PTSD. I’ve heard lots of policy experts, a couple retired general officers and a few medical professionals. But not a single returned combat veteran who has survived PTSD. So, as a combat veteran who has survived PTSD and now takes part in research and treatment for wounded warriors with PTSD and Traumatic Brain Injuries (TBI), I’d like to weigh in.

To the editors and entire staff of the New York Daily News: Screw You. Go to war, come home, go to war again. Keep this up for 10 years. Then see how funny you think that headline is. You have no standing to make this judgment. None.

To our elected officials and the people who elected them: this is what you get when you refuse to do what is necessary to create and maintain sufficient military force to fight your wars. This means everything necessary up to and including the implementation of a draft. We’ve been fighting for 10 years—twice as long as World War II—with insufficient forces.

The All-Volunteer Army was designed as a peacetime force. It was never supposed to carry us through 10 years of war. The National Guard and Reserves are supposed to be a strategic reserve. Congress and two successive administrations have worn the military down through misuse.

That said, this is one individual action apparently carried out by a single soldier. There are 2.4 million men and women who went to Iraq and Afghanistan and didn’t commit this horrific crime. Be proud of all of them and make sure you hold your elected representatives responsible to provide the care the returned veterans need once they are home.

To the well-meaning psychologists and psychiatrists who believe that the medical community should remove the word Disorder from the diagnosis of PTSD in order to reduce the stigma of soldiers seeking help: you’ve got it 100% wrong.

Instead of reducing the stigma of a soldier asking for help, this would increase it. Being wounded in the service of one’s country is entirely honorable. Seeking medical attention for “stress” is considered breaking. We know that PTSD changes the way the brain works and even its size and shape. That change makes this an injury, a combat injury. The diagnosis should be for Trauma-Induced Brain Injury or something similar.

I heard someone on the radio today say that PTSD is the common cold of mental health conditions. That’s really unlikely to lower the stigma of a soldier asking for help. From personal experience I can tell you I would have swapped a cold any day for the experience of sitting alone in the desert with a pistol in my hand ready to commit suicide because I couldn’t stop the images of dead and mutilated bodies from taking over my brain. No, most definitely not a cold. And not helpful.

As for the future of our mission in Afghanistan. In my experience with small wars, sometimes it is one seemingly small event that changes the course of history. In Kosovo, it was Racak: the murder of forty-five Kosovar Albanian civilians on a frigid January evening by Serbian police and soldiers stiffened NATO’s resolve to stop the violence. The bombing campaign began a few weeks later.

It’s profoundly unsettling to think that this event could have the opposite effect, weakening the resolve of the U.S. and its allies to remain in Afghanistan.