Gray Fox

The war in Iraq is over. But the memories and recollections will be with us for decades to come. It’s nice, for a change, to focus on those who dedicated their time in country to saving, rather than taking, lives.

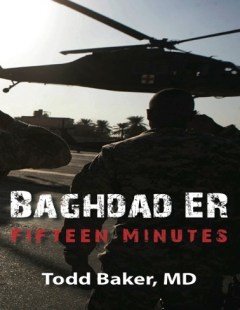

Dr. Todd Baker has just published Baghdad ER: Fifteen Minutes, about his tour as chief of the emergency section of the Army’s 86th Combat Support Hospital in Baghdad, from November 2007 to January 2009. The “Fifteen Minutes” in the title refers to quarter of the golden hour, after a troop is wounded, that his team would have to try to save a soldier’s life by the time he or she got to the hospital. iBattleland conducted this email chat with him earlier this week:

What was it like practicing medicine under fire?

Our team never backed down, regardless of the threat of rocket fire on a routine basis. For an eight-week period, our facility, along with Baghdad’s International Zone, received multiple rounds of incoming rockets each day. Our hospital was four stories in size, but our ER was a single-story section. Multiple times our command ordered the ER to evacuate all non-essential personnel, but our nurses, medics, and docs never left the ER. They put themselves in harm’s way routinely to care for their patients, and I could not be prouder of our team.

Did you ever find yourself wondering about the absurdity of trying to save lives in the middle of folks trying to kill one another?

To be honest, we did just our job and did not worry about those things. I guess it is ironic we tried to “undo” what had been done to our patients, and we would get especially frustrated when caring for traumatized children who had been wounded by the bad guys. Needless to say, when our troops were brought to us, we all felt an extra sense of duty to get those heroes home alive.

What do you think is the most important takeaway for readers from Baghdad ER?

There are three things I want readers to take away from this book:

1) How hard our young medics worked to save lives everyday.

2) How hard our troops worked to get their wounded buddies to us.

3) I want families to know that, should the worst happen, their loved one will get the best medical care in the world, from the battlefield all the way back to the U.S.

What kinds of injuries were the most common?

The most common injuries we encountered were gunshot wounds and blast injuries. The explosively formed penetrators, or EFPs, frequently caused amputations of extremities of our guys routinely, especially their legs. This was the type of injury that our team had to move quickly to treat as these troops would bleed to death very quickly.

What are the biggest improvements in battlefield medicine since 9/11?

1) Every American service member carries at least one tourniquet at all times. Tourniquets have saved thousands of lives over the past ten years.

2) Blood is now the resuscitation fluid of choice in trauma. It is given as rapidly as possible when our troops are wounded, and that use has now been adopted in American trauma centers.

What’s the biggest medical problem still out there?

Despite the amazing advances in trauma care, it is still difficult to stop bleeding and hemorrhage in injuries that are not compressible, ie you can’t use a tourniquet. Sometimes it is hard to get direct pressure to the spot that is bleeding. Many new dressings and anti-bleeding agents have been developed, but all have flaws.

Did it feel different treating Americans than Iraqis?

Of course the adrenaline flowed a little stronger when caring for our wounded heroes, but we did the best we could to save everyone.

Tell us about your most rewarding Baghdad ER success?

Every soldier, marine, airman, or sailor saved was a success. Anytime we were able to stabilize a dying American hero and put them on the path to recovery, it was as rewarding as anything I’ve ever done. To take a twenty-something year old kid, have them put in the trauma bed within minutes or even seconds of death, and then to save their life-our team took the most pride in that. I had no personal saves-they were all due to the amazing work of our nurses, medics, and trauma team.

Tell us about your most searing Baghdad ER failure?

Early in our tour, I was caring for a severely wounded Iraqi man who I struggled to place an airway in. I attempted a technique I was not as familiar with, and ended up not being successful. I learned that day to do what you are most experienced with and know best, and don’t try other techniques that you are not familiar with.

Did you ever feel like you were playing God out there?

To be honest, not at all. I’ve always felt that there are three players in a major resuscitation. The patient has to do their part, our team must to it’s part, and God does the rest.

Did you ever save someone’s life that, in hindsight, it might have been better if you had failed?

Some of the people we saved had amazing injuries, and I cannot imagine how tough life must be for them, assuming they survived long-term. However, we simply did the best we could every time.

Gray Fox

Tell us a little bit about yourself.

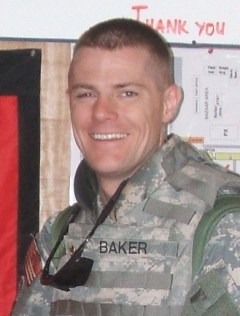

I am originally from Arkansas, and went to medical school on a U.S. Army HPSP scholarship, as I always knew I would be affiliated with the military in some form. I entered active duty upon graduation from medical school in July of 2001 and trained in emergency medicine until graduating from residency in 2004. I then spent two years as the Regimental Surgeon of the 2d Cavalry Regiment as it transitioned into one of the Army’s new Stryker Brigade Combat Teams.

Transferring to Madigan Army Medical Center, I spent a little over a year as a Professor of Emergency Medicine teaching EM residents before being sent to the 86th Combat Support Hospital to deploy as chief of the Emergency Treatment Section, or EMT. After fifteen months as chief of “Baghdad ER,” I got out of the military after almost eight years and now serve as the medical director of the emergency department at Skaggs Regional Medical Center, Branson, MO.

Do you like watching M*A*S*H? Which character are you most like, and why?

My colleague, Jason Cohen, DO, had the entire series on DVD, and I watched it a few times with him. We took pride in being the Hawkeye and BJ of our unit, at least in our eyes. Our uniform codes were very strict, but Jason and I would frequently sit on the rooftop enjoying cigars in our smoking robes and drinking near-beer out of plastic martini glasses my wife had provided to us.