A long time ago, and far away, the U.S. invaded and occupied the Philippines. There are parallels to recent U.S. military campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq, down to torturing the enemy.

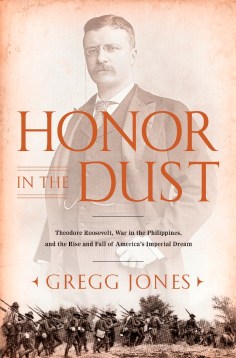

Journalist Gregg Jones has written Honor in the Dust: Theodore Roosevelt, War in the Philippines, and the Rise and Fall of America’s Imperial Dream, in part, to remind us that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. Battleland conducted an e-mail chat with him earlier this week:

What is the most surprising thing you learned in researching and writing Honor in the Dust?

There were so many surprises, which made this project a wonderful voyage of discovery for me. But here are two of the biggest:

— I knew that Theodore Roosevelt was central to my story when I began my research, but I was astonished by the extent to which the Philippines dominated his thoughts from 1898–1903. Roosevelt wrote incessantly about the Philippines in his private letters and spoke about the islands in countless public speeches. He dreamed of becoming America’s first governor there. And he devoted much energy and political capital to keeping the U.S. on course in its quest to annex and pacify the islands. He was fairly consumed by the Philippines during those years.

— I was surprised by what I learned about William Howard Taft, who used his high-profile position as America’s first civilian governor in the Philippines as a stepping-stone to the presidency in 1908. History has remembered him as “Big Bill” Taft, the genial 350-pounder who loved to play golf and was the benevolent friend of America’s “little brown brothers” in the Philippines. In fact, he was a nasty bureaucratic infighter who undermined his rivals in America’s colonial venture in the Philippines. Furthermore, the sincerity of his public displays of friendship toward Filipinos is called into question by private actions that were harsh and sometimes racist.

Sum up Honor in the Dust.

Honor in the Dust is the story of America’s thrilling rise to the world stage in the Spanish-American War of 1898 and its fall from grace in the Philippine-American War that followed. It’s the story of America’s soaring dreams of empire at the beginning of the 20th century, propelled to a large extent by Theodore Roosevelt, and the painful collapse of those dreams when our crusade to liberate the Philippines from Spanish rule became a war of colonial conquest.

Your book casts long shadows involving American hubris: foreign invasion and torture. Is this something in America’s DNA?

Hubris is not unique to the U.S., and I certainly don’t believe that Americans are genetically predisposed to torture and wars of conquest. The U.S. was late to the colonial game, and the drivers of America’s expansionist quest at the end of the 19th century took their cue from those European powers that had excelled at the “great game” unfolding across Asia and Africa. The Europeans waged ruthless warfare on their unwilling colonial subjects, and torture was a common tactic.

During the U.S. Senate hearings of 1902 on America’s conduct in the Philippines, one U.S. general testified that Europeans found America’s treatment of the Filipinos naively gentle. I don’t doubt that this was the prevailing view among Europeans at that time. But the concern of many Americans who opposed our conquest of the Philippines was not how our actions compared with those by European powers, but whether we had lived up to American values and principles. That’s a lofty standard but one that sets America apart from most of the world.

History is littered with examples of great powers that become overconfident and engage in “imperial overreach.” Arrogance breeds intellectual laziness, and that fosters a disregard for the lessons of history. This isn’t unique to America — you can trace this continuum back through the ages. I think that history shows us that a nation is in peril when its citizens come to believe they are so powerful and omniscient that there is no need to look or listen before acting.

We Americans aren’t alone in preferring to forget painful episodes in our history. Many Japanese deny that their country committed war crimes in World War II. Many Belgians refuse to accept that King Leopold’s colonial regime perpetrated genocidal excesses in the Belgian Congo. Many British choose to forget the injustices and brutality of the Boer War (which played out at the same time as America’s war in the Philippines). And so on.

I believe it’s vital for Americans to know the history of their country, warts and all. The world’s great religions teach the virtues of reflection and self-examination. Business schools train future executives and entrepreneurs to critically analyze case studies. So why would any American consider it unpatriotic to study the entire expanse of their history? I’m not advocating an exercise in self-flagellation, but, rather, a study of our history as part of the never-ending quest for the “more perfect union” envisioned by the framers of our Constitution in 1787.

Most Americans rarely think of the Philippines or of the Philippine people. What are the most important things they should know about each other?

Filipinos, on the whole, have a much better sense of the U.S. and the American people than vice versa. That’s because so many Filipinos have lived in the U.S. or traveled there or they have family in America. Still, I think too many Filipinos overestimate the wealth and power of Americans and the ability of the U.S. to influence events inside and outside the Philippines. On a personal level, most Filipinos are inclined to like Americans. American pop culture is more deeply rooted in the Philippines than any other place in Asia (much to the dismay of Filipino nationalists).

On the other side of the equation, I’ve spent much of my adult life trying to understand the Philippines. It’s a complicated country, a land of exquisite beauty alongside unspeakable squalor. Its people are intelligent, talented and hardworking, and they can be wonderfully gracious and generous.

But, like most places in the world, there is a dark side to the Philippines. It’s a place of appalling poverty and injustice, a blighted land where too many politicians, businessmen, religious leaders and ordinary citizens allow greed and self-interest to triumph over rule of law, justice and the common good.

The fact that the country is scattered across thousands of islands has stunted social, economic and political development. So has the legacy of colonialism — more than three centuries of Spanish domination, followed by 47 years of American rule. The Philippines became a nominally independent nation only in 1946, so its institutions remain weak and fragile, and its sense of national identity is still embryonic.

This is a far-away and dark corner of U.S. history … how did you come to do this book?

Penguin

In 1984, I was a 25-year-old reporter at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. I loved reading history, especially American history, and I had the dream of traveling to some distant land to write about historic events as they unfolded. I scraped together every penny I could, sold some furniture and bought a one-way ticket to the Philippines.

I wound up spending five eventful years there, chronicling the overthrow of Ferdinand Marcos in the People Power revolution of 1986 and other events for U.S. and British newspapers. I also began work on a book about the communist revolutionary movement in the Philippines, Red Revolution. As part of my research for that project, I immersed myself in America’s history in the islands. I was fascinated by what I read and surprised that I’d never read about these events in my history books. I knew then that I wanted to write Honor in the Dust someday.

Assess Theodore Roosevelt for us in a nutshell: Has he gotten too much of a free ride from historians?

Historians have tended to gloss over the Philippine war-crimes scandal that Theodore Roosevelt endured in the first year of his presidency because of all the extraordinary achievements that followed. I don’t fault them for that.

If your objective is to assess the totality of Roosevelt’s career in public life, or even his presidency, his trouble in the Philippines is a blip. But that doesn’t mean it should be erased from our national memory bank.

I thought this was a forgotten chapter in American history that was important and needed to be reclaimed, especially given its relevance to contemporary events. This wasn’t Theodore Roosevelt’s finest hour. Many things he did regarding the Philippines and the war-crimes revelations in 1901–02 were not admirable. But his legacy as a great President is very much intact.

The U.S. has had a long and mixed record in the Philippines. New protests are erupting in Manila over expanding the U.S. troop presence in the country. On the whole — and with the hindsight of history — should the U.S. be in the Philippines?

Theodore Roosevelt and other American expansionists had a grand vision for the Philippines: we would remake the islands in our image, as a beacon of liberty, enlightenment and economic prosperity in Asia. U.S. colonial rule delivered a system of universal public education, infrastructure and the trappings of democracy and civil society.

But Roosevelt’s grand vision for the islands was never fully realized, and the country’s economy and democratic institutions suffered during the U.S.-backed dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos in the 1970s and ’80s. When the U.S. was forced to close its two huge U.S. military bases in the Philippines in the 1990s, the nature of the relationship changed dramatically.

The U.S. and the Philippines have been trying ever since to define the parameters of their new relationship. I believe that most Filipinos still welcome a U.S. presence in the islands, but they want a partnership of equals. There’s no question that a majority of Filipinos would rather see the U.S. as the dominant power in Asia than China.

On the domestic front, I believe the U.S. should do everything possible to help the Philippines strengthen its democratic institutions and develop a sustainable economy capable of supporting the country’s spiraling population. But Filipinos themselves have to take responsibility for their future. They have to demand more from their political leaders and hold them accountable to forge a more prosperous and peaceful future in the Philippines.