Stuart Bowen testifies on Capitol Hill

Now that the U.S. military has left Iraq, it’s time to tally how much the nation wasted putting it back together. Stuart Bowen, the special inspector general for Iraq reconstruction, bluntly calls it a “disorganized American occupation” that frittered away at least $6 billion.

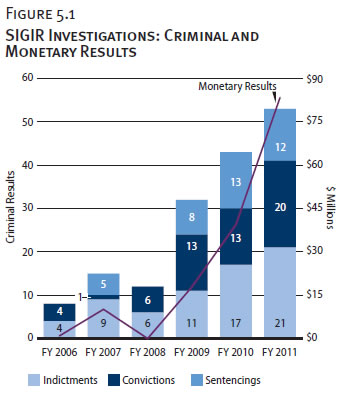

He rattles off the numbers like a machine gun set on automatic fire: his auditors have documented at least $6 to $8 billion of the $61 billion the nation spent reconstructing Iraq was wasted in sloppy contracting and inefficiencies. A total of $170 million in fraud has been found and recovered from 61 convicted contractors. All told, Bowen’s band of green-eyeshaded bean-counters has collected close to $1.7 billion in mal-spent – or maliciously-spent — federal funds inside Iraq.

SIGIR

“It was abnormal and unnecessary,” he tells Battleland, “but certainly unsurprising given the fact that we were not structured in 2003 to carry out an overseas rebuilding operation that cost tens of billions of dollars.” Bowen, who has been on the job for an amazing eight years, recalls that the original U.S. mission in Iraq was “liberate and leave” – something that was supposed to be wrapped up in three months. But the looting and lawlessness that happened following the 2003 invasion – and the lack of U.S. troops to deal with it – turned that modest mission into a far longer and more costly one.

“An ad-hocracy was created to manage this occupation,” Bowen says. It was, he says, plagued by three major shortcomings:

1. There was no “unity of command in post-war reconstruction,” he says. “We do not have a structure in place that has the capacity to carry out inter-agency stabilization operations.” The haphazardness led to waste on a massive scale. “Six to eight billion, minimum,” Bowen says, “was wasted.”

2. The lack of military contracting experts let contractors get away with monetary murder. “We didn’t have enough contracting officers to oversee these huge, $100 million contracts,” Bowen argues. “We were unable to effectively manage cost-plus contracts, which I call an open checkbook for the contractors. They were unmanaged, and were wasting hundreds of millions of dollars in taxpayer money.”

And given the Wild West atmosphere that existed in Iraq following the invasion, Bowen suggests recovering even $170 million was pretty remarkable. “There’s a lot more out there,” he says simply, when asked how much fraud took place. “Trying to catch crooks in a war zone that’s entirely cash-driven has been very difficult,” he says. “We catch most fraud in the United States through electronic means, but in a war zone — where everyone has a weapon — there aren’t many people willing to come forward and say `He stole the cash.’”

3. The churn among U.S. contract-overseers, both military and civilian, and the resulting lack of sustained oversight of contractors, made waste all but inevitable. “How do you do an eight-year rebuilding program when no [U.S. government contracting officer] stays in the country, from top to bottom, virtually longer than a year?” Bowen asks. Even normal, year-long tours boiled down to six months of effective oversight once contract managers figured out what they were supposed to be doing, and how to do it. “There’s this flux of variously qualified individuals moving in and out of Iraq at an extraordinary pace trying to manage one over-arching rebuilding program,” Bowen says. “I’ve just described something that’s impossible to do.”

Iraq is littered with costly American good intentions gone sour, including “spending $40 million on a prison that will never hold an Iraqi prisoner in Diyala province, one of the still most dangerous provinces in the country,” Bowen notes. “The Iraqis call it the `whale in the desert.'”

He repeats a refrain heard before: the nation needs to have a standing force of reconstruction specialists ready to go before the next major war. It’s as vital a part of the war-making toolkit as troops and tanks. “Stabilization operations are part and parcel of protecting our national security interests around the globe – we’ve been in one every year but two since 1980,” Bowen says. Absent a better way of fixing what’s broke, “perhaps that’s the largest lesson from Iraq and Afghanistan – don’t engage in $60 to $70 billion 10-year stabilization operations.”