U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta speaks to military personnel during his visit to Camp Lemonnier, Dec. 13, 2011 in Djibouti.

The Pentagon’s predicament is not just that it needs to adjust its spending level and galaxy of programs to new, lower amounts. It needs, indeed it literally is unable to survive without, fundamental reform.

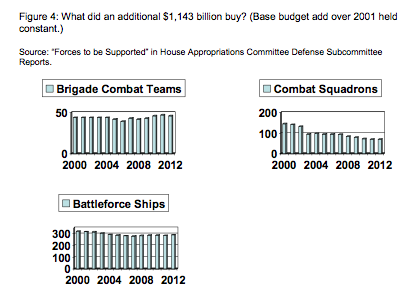

Since 2001, the Pentagon budget has grown by $1.3 trillion to fund the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; the base (non-war) DOD budget has grown by an additional $1.1 trillion. How much has the size, modernity, and readiness of our forces grown as a result of the extra basic Pentagon budget funding? See Figure 4.

The number of Army brigade combat teams has remained essentially flat since 2001. The Navy’s “battle force” has shrunk by ten percent. The number of active and reserve Air Force combat aircraft squadrons has shrunk by 51 percent.

These are not smaller newer forces; they are smaller older forces. In each service the average age of major equipment inventories is significantly greater than it was in 2001.

These forces are also now less combat ready and/or trained, not more. In 2006, the House Armed Services Committee released information that showed major Army combat formations in the US have lower readiness ratings than before 2001. The information has not been publicly updated, but we should worry that it is worse, not better. For the past few years, the press has reported pervasive maintenance and readiness problems in the Navy’s ships. In the Air Force, fighter pilots now get less training time in the air than they did in the low-readiness era of the 1970s, even less than they received in the 1990s.

Some Washington politicians and think tank types assert that we have such a big edge over our potential enemies that we now can afford to reduce our forces. The fact of the matter is that the enemies we have faced have been either grossly incompetent and unable to fight, like Saddam Hussein’s hopelessly inept and unmotivated conventional armed forces, or woefully under equipped and tiny, even if all to willing to fight and die, like the insurgents in Iraq and Afghanistan. They have no armored vehicles, no air force or air defense and no navy. As one retired Army colonel puts it, since 2001 we have only been clubbing baby seals as opponents. The repeated claims we hear that US armed forces are the best in the world, even the best in history, are driven by politics, not facts.

That the anti-US factions in Iraq have now successfully rid their country of us and that the Taliban in Afghanistan is making the fight there so difficult for us derive from political and other factors in an insurgency. These outcomes occur despite the heroism and skill of US forces in both countries at the fighting unit level.

While we do not face any existential threat now, at some point in the future US armed forces may be required to confront a substantial, well armed, highly trained, even inspired enemy. Should that day come, we clearly do not want our forces to be the victims of civilian and military decision-makers that permit our forces to decay, even when the budget has been growing. Imagine what such deficient managers will inflict on our forces with declining budgets.

The coming cuts make the reform of three key factors a highly urgent matter: leadership, decision-making, and hardware programs immediately need fundamental renovation, if not revolution.

Starting with the easiest, but hardly uncomplicated, hardware issues first, the anti-reform approach—business as usual—will mean stretching out procurement programs, such as aircraft purchases, and reducing the total buy. Advertised as saving money, they will actually make already unaffordable programs even more expensive in the long run (by raising unit cost), and they also almost always mean giving our combat forces second rate equipment, such as the F-35 (an inferior fighter, a mediocre short range bomb truck, and a substandard attack aircraft for troops engaged in combat). Failed, unaffordable programs such as the F-35 need to be terminated, not put on life support. There are many such disappointments still in the Pentagon’s too-long list of Major Defense Acquisition Programs. To help identify them for DOD’s current management, further procurement of any hardware program that has not completed and passed all operational testing should be suspended, pending the availability of empirical evidence of just what the new weapons are and are not capable of—and what they actually cost.

To reform the decision-making process, managers also need to know, rather be confronted with, realistic cost estimates. Today, they routinely take in what the program advocates want them to have in order to facilitate a decision to go ahead with a program. The information environment of the Pentagon needs to be radically reformed with the omnipresence of audits and evaluations, only by independent parties, especially of major programs and policies now facing go, no-go decisions.

Instead of a pervasive audit mentality in the Pentagon, we have a string of broken promises for achieving financial accountability, or rather conveniently defined financial management objectives. A classic example is Secretary Panetta’s decision to accelerate the goal to audit the Pentagon’s “statement of budgetary resources” by 2014, not 2017. Even if the goal were to be achieved, it would satisfy only some of the requirements of the Chief Financial Officers Act from back in 1990, and it would satisfy even fewer of the accountability requirements of the US Constitution. Also, it would produce little to nothing to help decision-makers understand the downstream implications of their program decisions.

If Pentagon management were truly interested to face the coming era of budget reductions seriously and constructively, it would move ahead with ruthless determination on the audit front, rather than toss up reassuring bromides devised by bureaucrats seeking to preserve traditional behavior. Despite the appearance of movement, Panetta has been as disappointing on this matter as anywhere. His decision to accelerate a narrow audit goal, already delayed from 1990—if not 1787—is at least as disheartening as his lurid but unsubstantiated budget rhetoric.

Typical of secretary Panetta’s decision-making up to now is his instruction to DOD budgeters to not prepare a 2013 budget that meets the spending levels now imposed by existing law (i.e. the “Doomsday Mechanism”): Reductions that are, in truth, unremarkable in historic terms. Time is fast running out.

Most in Washington today speculate that with a year to legislate before the required sequester occurs in January 2013, Congress will find the motivation and votes to undo the act, especially after the elections of November 2012. This Congress has provided no basis for any such expectation. Its Members have proven capable only of maneuvering for selfish advantage; that the next election will be two years away, rather than one, is clearly irrelevant to them and any expectation of statesman-like behavior. The lame duck session of Congress now scheduled for the aftermath of the 2012 elections is most likely only to be yet another debacle.

It would clearly be prudent for the Defense Department to prepare now and submit this February, when the new 2013 budget is due, a plan for meeting DOD spending at the “Doomsday” level set by current law. To expect rescue from Congress is foolishness. The Defense Department needs to have its own plan.

Panetta’s refusal to cope with a future now set by law to occur suggests the most critical reform issue. Fixing hardware acquisition and decision-making are necessary, but they are also insufficient for a reformed Pentagon. Remodeling the civilian and military leadership is the essential ingredient to the survival, even prosperity, of our forces in the future at lower spending levels. Managers who can be maneuvered, even forced, into making the right decisions may be a step in the right direction, but they are not a reasonable basis for hope. Managers who refuse to make any adjustment in the face of likely events, and who use politically charged rhetoric to distort the perception of realities, are obviously an impediment to coping with the future. Secretary Panetta is such a manager.

Is this the man we want and need to be secretary of defense in the era that is coming?

Winslow Wheeler worked on national security issues for 31 years for members of the U.S. Senate and for the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO)