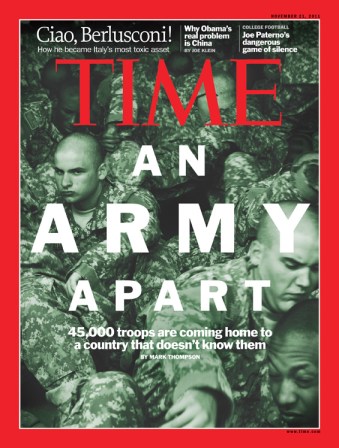

Our November 21 cover

The U.S. military and American society are drifting apart. It’s tough inside the civilian world to discern the drift. But troops in all the military services sense it, smell it — and talk about it. So do their superiors. We have a professional military of volunteers that has been stoically at war for more than a decade. But as the wars have droned on, the troops waging them are increasingly an Army apart.

This is the topic of my cover story in the dead-tree edition of Time out today – Veterans’ Day eve. It’s an important story, one that needs to be widely told. But because TIME keeps its print edition off the web for awhile, what follows is sort of a director’s cut of what’s in the magazine.

(READ: Rehabilitating America’s Wounded Warriors — An Inside Look)

The civilian-military gap has taken on an edge recently, driven by the lack of sacrifice — either in blood or treasure — demanded of the rest of us compared to what the troops are giving. Army Sgt. 1st Class Leroy Petry recently earned the Medal of Honor for saving Ranger buddies from certain death in Afghanistan. He grabbed a live grenade and tossed it away as it blew up. It cost him his right hand. It happened on his seventh combat tour (he has since pulled an eighth). A roadside bomb killed Sgt. 1st Class Kristoffer Domeij, husband and father of two, in Afghanistan Oct. 22. He was on his 14th combat deployment.

“There’s no challenge for the 99% of the American people who are not involved in the military,” says Army veteran Ron Capps, who served as an intelligence analyst in Afghanistan. “They don’t lose when soldiers die overseas, they’re not being forced to pay, for the wars, and there’s no sense among the vast population of what we’re engaged in.”

Military leaders know the gap is widening, which leads to important questions: is this a bad thing? If it is, should we care? And if we should care, what can be done to reverse it? “I have this deep existential angst about a military organization within a democratic society that’s as isolated from the rest of that society as our military is becoming,” says Michael Desch, a political scientist and military expert at Notre Dame. “The gap can make civilian control of the military harder to achieve.”

That may be a reach, but senior officers sense the parting. “I have been struck in my travels at the lack of what I would call in-depth understanding of what we’ve been through,” Admiral Mike Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs, told Time before he retired last month after 43 years in uniform. It’s almost like the American Foreign Legion. “We come from fewer and fewer places — we’ve BRAC’ed our way out of significant portions of the country,” Mullen said, referring to the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission process that has shuttered hundreds of military posts across wide swaths of the nation. “Long term, if the military drifts away from its people in this country, that is a catastrophic outcome we as a country can’t tolerate.”

(PHOTOS: America’s Other 1% — The Army Apart)

More evidence of the military’s growing separateness: it is becoming a family trade. Mullen has had two children on active duty. His successor, Army General Martin Dempsey, has had three. General Ray Odierno, the new Army chief of staff, has a son who lost his left arm to an RPG in Iraq in 2004. Of course, there are other ways of looking at it. “It is truly inspiring to see the same commitment to serve this nation passing to a new generation of leaders who will follow in the footsteps of their fathers,” Defense Secretary Leon Panetta said as Mullen handed off the baton to Dempsey Sept. 30. Fair enough. But what about the rest of us?

Call it the law of unintended consequences.

Former defense secretary Robert Gates raised the topic last month at the U.S. Military Academy. “In the absence of a draft that reaches deeply into the ranks of the citizenry, service in the military — matter how laudable — has become something for other people to do,” the former defense secretary told the West Point cadets three months after leaving office.

The U.S. never had a standing peacetime army until after World War II, and until 1973 it was filled with conscripts. The nation has been fighting its longest war on the backs of the smallest slice of its population in more than 200 years. “Not since the peacetime years between World War I and World War II,” a Pew study noted last month, “has a smaller share of Americans served in the armed forces.”

We used to call them “soldiers,” and that was good enough when they were one of us. But now civilians call them “warriors” or “war-fighters,” as if the label proudly and honorable worn by their fathers and grandfathers is somehow inadequate. “There is a small subset of our population that is bearing the burdens of service in uniform for all,” then-Army general Dave Petraeus told Time before shucking his Army uniform to run the CIA. “But it is also important indeed that all citizens be acquainted with what it is that our men and women in uniform do for our country.”

But that’s not happening. Steven Blum, a retired three-star Army general who ran the National Guard from 2003 to 2008, fears the wars have become “a constant background noise, because so few of U.S. citizens really are engaged in this conflict.” Except for hometown reservists heading off to war, he warned a congressional committee last month that the U.S. military could “become viewed by the American people as a foreign legion, or a mercenary unit.”

(PHOTOS: Returning Soldiers’ Tattoos — Battle Scars)

Neither the U.S. military nor civilian society is to blame for the drift. In fact, fundamental changes in each have made it inevitable. Only 1.5 million of the 240 million Americans over 18 – about half of 1% — are in uniform today. Without a draft or a good civilian economy, they tend to stay in uniform longer, further isolating them from the American mainstream. During the Vietnam War, fewer than 20% of Army grunts had more than four years in uniform; today it’s more than half.

The military is no longer – if it ever were — a last resort for poor young Americans with no other options; nearly all are high-school graduates and most come from the working and middle classes. Yet it is self-selecting, and increasingly well paid. Average cash compensation per troop is $57,400, and the annual total personnel-related cost per troop, including health care, is more than twice that: $121,600, according to a recent accounting by the independent Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments.

Part of the problem – surprise! – is Pentagon penny-pinching. Trying to save money, the Defense Department has been shutting bases down across much of the nation for the past generation, and concentrating them in military-friendly southern states. “Where [troops come from] gets more and more away from the general population,” ex-Guard chief Blum said. “What they do behind those gates is pretty much, `Who cares?’ to the general population, unless they make their living off of what goes on in there.”

Even as the military has changed dramatically over the past generation, so has the country in which it is rooted. Without any skin in the game, Americans are detached from the conflicts and those waging them, with the exception of Memorial Days and the magnetic yellow ribbons that cling to the rump of their SUVs. There are no advertisements tied into the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as there were in World War II. Even Vietnam, an unpopular war, generated songs (“And it’s one, two, three, what are we fighting for?”) because we all, more or less, had a stake. Today, every man and woman wearing the uniform of the U.S. military is a volunteer, we tell ourselves (although hireling might be a more apt word).

Following the debacle that was Vietnam, creating the all-volunteer force seemed brilliant: delinking the military from an inconstant public gave the President a stronger hand in sending forces into harm’s way, especially given Congress’ cravenness when it came to being spattered with GI-positive blood. But it also carries with it a risk: that it will too often been seen as a convenient hammer to deal with vexing international problems. “A standing army, however necessary it may be at some times, is always dangerous to the liberties of the people,” Samuel Adams of the American Revolution (and beer fame) warned. “Soldiers are apt to consider themselves as a body distinct from the rest of the citizens…Such a power should be watched with a jealous eye.”

(WATCH: Reunion and Recovery After an Iraq Injury)

The makeup of today’s force misses the heart of American might: the common bond between the U.S. military, and the citizens who supply and fund it, is the fulcrum that leverages U.S. power. Divorced from society, the military runs the risk of becoming little more than rent-a-cops with bigger weapons. And, in fact, as the U.S. pursued two wars post-9/11, it became clear quickly that it could only wage them if it hired costly contractors to do most everything except pull triggers in the war zones (although they did some of that, too). The CIA increasingly is killing purported terrorists with drone-launched Hellfire missiles around the world, with no public acknowledgement or accountability.

Shifts in how the U.S. wages its wars are always subtle. But as the military and society drift further apart, the three-way debate — with Congress representing the body politic – has withered. Instead, it has turned into a tug-of-war between the White House and the Pentagon. Without the ballast provided by a substantial public investment in how military force is used, it becomes easier for both sides to game the system envisioned by the Founding Fathers: forcing the public to act as an industrial-strength flywheel on military excursions.

So what’s the solution? What about a return to the draft? The public doesn’t like the idea. In last month’s Pew poll, 68% of veterans and 74% of the public oppose its return (interestingly, 82% of post-9/11 veterans feel that way, but only 61% of Vietnam-era vets do). The military agrees. Asked by Time what steps the Pentagon is considering to trim its budget, Marine General James Cartwright, until recently the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, listed personnel as a big target. “We have to look at everything,” he said three weeks before he retired, including “the dirty word, `draft.'”

But if this growing gap is something we need to fix before it becomes a chasm, there are several things the nation needs to do. The first is to stop fighting war on the cheap, both fiscally and politically. Borrowing money to wage war is a false economy (wars tend not to age well; imagine how you’d feel if you were paying for Vietnam today).

Politically, Americans should insist their elected representatives stop passing the buck. They don’t want to make the tough calls when it comes to budget cuts, so they appoint a super-committee to do the dirty work. They don’t want to target military bases for closing following the Cold War, so they commanded special outside panels to do it.

Most importantly, they’ve subcontracted out making war to the President, despite Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution, which gives only Congress the right “to declare war.” The latest slip down this slippery slope: on Oct. 14, the White House simply informed Congress, by letter, that it is sending 100 U.S. troops to aid in the central African war against the Lord’s Resistance Army.

War is the most extraordinary enterprise in which the national government engages. It’s long past time the public to engage in it, as well.

SPECIAL REPORT: TIME’s Complete Veteran’s Day Coverage