If you’ve been paying attention, you may have heard that President Obama has pledged to cut $400 billion out of security spending between now and 2023. But what you may not know is that the $400 billion won’t be a cut as far as Joe and Jane Taxpayer are concerned. Todd Harrison, Washington’s defense-budget wizard, says letting Pentagon spending grow along with inflation, between now and 2023, actually will yield more than the $400 billion in savings Obama is seeking. Keep your eye on the ball here: the $400 billion in cuts aren’t cuts as you and I understand them — they are reductions in the projected future rate of growth. And because defense spending has close to doubled over the past decade — with future spending increases folded into future budget plans as naturally as dew forms on the morning grass — the U.S. military finds trimming its future spending to the rate of inflation a near-death experience.

“I think we need to cut defense,” Obama said Friday, “but as commander-in-chief, I’ve got to make sure that we’re cutting it in a way that recognizes we’re still in the middle of a war, we’re winding down another war, and we’ve got a whole bunch of veterans that we’ve got to care for as they come home.” But as Harrison, the budget whiz at the independent Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments makes clear, the Obama Administrations has proposed no real spending cuts for the Pentagon. Beyond that, the analysis of the 2012 budget he released Monday contains some interesting facts:

(PHOTOS: The U.S. Military in the Pacific)

— The average troop will be paid $57,400 in 2012, including various allowances for housing and subsistence.

— The cost of deploying one soldier to Afghanistan will be an estimated $1.2 million in 2012.

— The cost of the war in Libya to the U.S. is 1% of the cost of the war in Afghanistan.

— The average cost to fly an Air Force plane for one hour will be $23,800 in 2012.

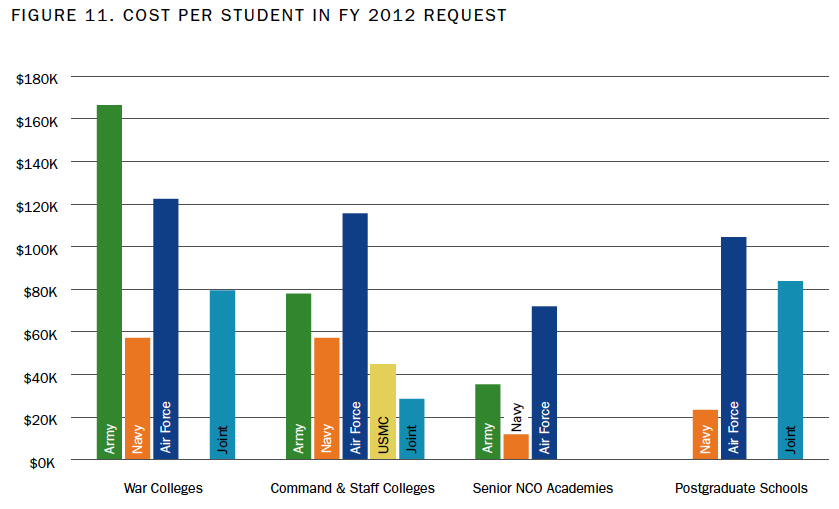

— The cost of a mid-career officer taking a year off for extra schooling ranges from $57,000 at the Naval War College in not-so-cheap Newport, R.I., to $166,000 in not-so-expensive Carlisle, Penn., at the Army War College. (“DoD maintains four separate war colleges, four command and staff colleges, three senior non-commissioned officer academies, and multiple postgraduate schools, such as the Air Force Institute of Technology, the Naval Postgraduate School, and the Industrial College of the Armed Forces,” Harrison notes.)

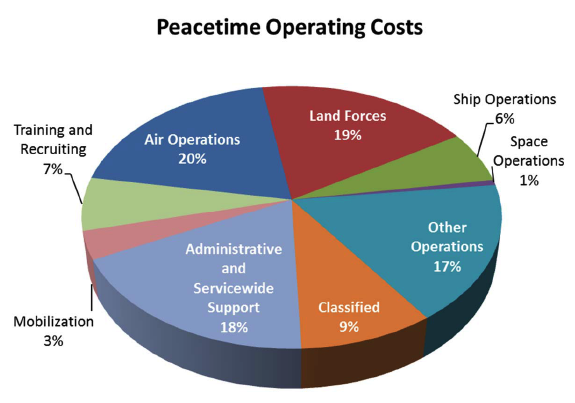

— Ships’ peacetime operating costs are one-third those of aircraft.

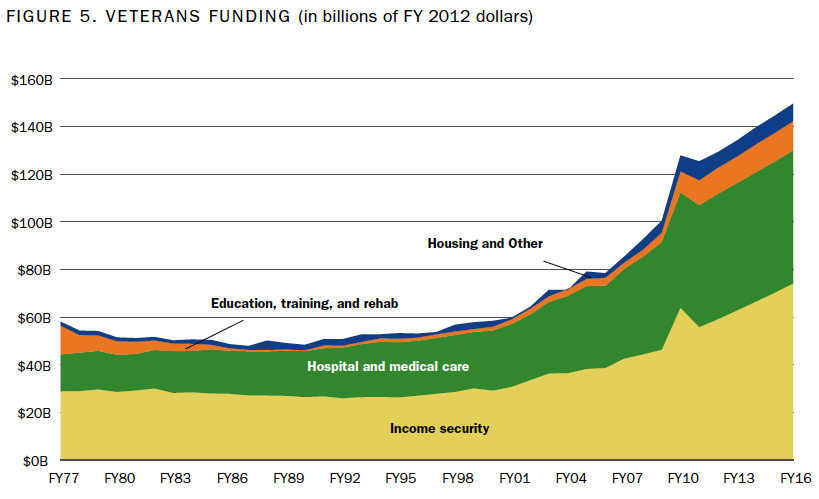

— Spending on veterans has more than doubled since 9/11, and shows no sign of slowing down, even as the number of veterans shrinks.

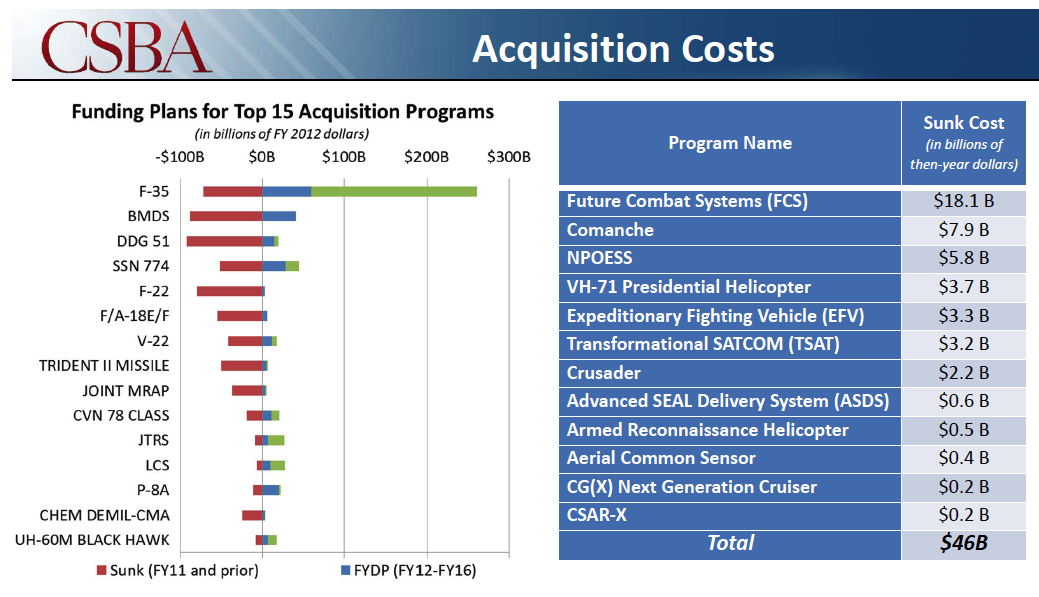

— Like a child at his first “all-you-can-eat” restaurant buffet, the Pentagon loaded its plate with “nice-to-have” weapons and systems that ultimately proved too costly or difficult to buy. Harrison put together a “dirty dozen” of such systems cancelled over the past decade on which taxpayers spent $46 billion — and didn’t get a single truck, tank, boat or plane out of the investment.

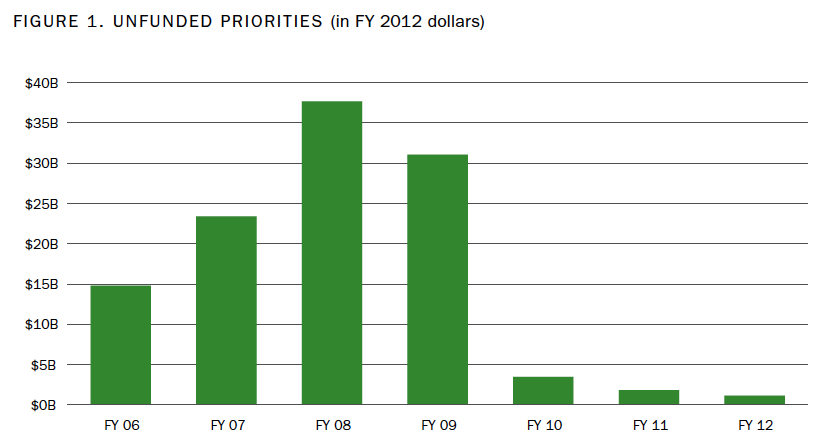

— For years, the military services colluded with friendly committees on Capitol Hill in creating so-called “unfunded priority lists.” More commonly known as “wish lists,” they were rosters of all the weapons the services wanted but penny-pinching defense secretaries wouldn’t let them have. When this got completely out of control several years ago, then-defense secretary Robert Gates ordered the services to submit such lists to him before sending them to Congress. The lists — once cited as vital to national security — have all but disappeared since Gates’ edict. Funny how that works.

“Nearly all of the unfunded priorities submitted to Congress are in procurement and operations and maintenance,” Harrison writes. “This indicates that if the Services had additional funding available they would prioritize the maintenance of existing equipment and would procure additional equipment or spares to augment their inventory.”

(LIST: Gears of War: Inside America’s Incredible Military Arsenal)

But while the wish lists may have gone away, wishful thinking apparently has not. Ashton Carter, the Pentagon’s top weapons buyer, spelled out the Defense Department future spending priorities last Friday. “Everyone has to look at everything,” he said. “But procurement and force structure should be the last thing.”