Should the U.S. military allow women to serve in ground combat — largely in infantry and armor units — to help their careers? A new report from the Military Leadership Diversity Commission says yes. It argues that the battle lines in Afghanistan and Iraq have been so blurry that women basically are in combat, but don’t get the formal combat credit needed to advance in rank. That’s because of a 1994 Pentagon ban — the so-called “combat exclusion rule” — that keeps females out of small units where most combat takes place. The rule should be junked, the commission says.

The panel, created by Congress in 2009, spent 18 months coming up with ways for the Pentagon to improve the promotion of women and minorities as the nation becomes increasingly diverse. “The armed forces,” it warned Monday, “have not yet succeeded in developing a continuing stream of leaders who are as demographically diverse as the nation they serve.” The 30-member commission included current and former military personnel as well as civilians.

The panel focused on 10 topics, including the definition of diversity, legal implications, recruiting, leadership and promotion. None dealt explicitly with combat effectiveness. But the commission did say it recommends that current standards for the combat arms remain in place, and not be relaxed to make it easier for women to join their ranks. The report, as a whole, reads more like a personnel manual than a combat-effectiveness manual. It recommends the creation of a “chief diversity officer” — CDO — who would report directly to the defense secretary.

The nation grappled with this issue in the early 1990s in the wake of the Navy’s Tailhook scandal, where scores of women were sexually assaulted at a naval aviators convention in Las Vegas. Hearings conducted then revealed a split between female officers — who were eager to get promoted, and saw combat as the best way to do that — and female enlisted troops, who were far less interested in going into harm’s way.

But that’s changing, according to Lester Lyles, the commission chairman and retired Air Force general. “Women serve — and they lead — military security, military police units, air defense units, intelligence units, all of which have to be right there with combat veterans in order to do the job appropriately,” he told the Associated Press. The commission heard from a panel of enlisted women a generation removed from those who testified when the combat exclusion rule was under consideration. “I didn’t hear, ‘Rah, rah, we want to be in combat,’” Lyles told the AP. “But I also didn’t hear, ‘We don’t want to be in combat.’ What they want is an equal opportunity to serve where their skills allow them to serve.”

Overall, the commission found that U.S. military leadership is too male and too white. “Racial/ethnic minorities and women are still under-represented among the Armed Forces’ top leadership, compared with the service members they lead,” it says.

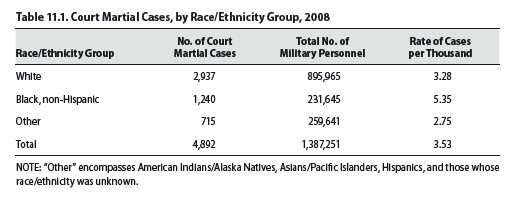

The fact that commanders court-martialed black members of the services at nearly double the rate of their white counterparts in 2008 shows “that the process has failed differentially for black service members.” The commission says it isn’t quite sure why this happened, but suggests “in-depth analyses of such data could be undertaken by the CDO.”