Gustave Whitehead was a German-American aviator who designed and built gliders and other flying machines. Some say it was Whitehead, not the Wright Brothers, who was first in flight.

Early last year, freelance aviation historian John Brown sat in the office of the curator of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, home of the 1903 Wright Flyer, the plane widely considered first in flight. At the time, Brown was doing research for an upcoming program on the Smithsonian Channel, and everything was going along fine until the curator, Dr. Tom Crouch, noticed that Brown had written the name of Gustave Whitehead, a German-born aviator, into his notes.

“He said, ‘You’re not writing about Whitehead, are you?’” Brown says. “And I said, ‘Well, I have to, Tom. It’s part of the history.’ And he glared at me for a while, and the temperature in the room dropped, and then he said, ‘You know he didn’t fly right?’”

Since the 1930s, a small contingent of aviation enthusiasts has argued that it was Whitehead – not Wilbur and Orville Wright – who was first in flight. That instead of the Wright Flyer taking off at Kitty Hawk on Dec. 17, 1903, history books should be teaching about the Whitehead No. 21 monoplane in Fairfield, Conn., on Aug. 14, 1901 when Whitehead allegedly made the world’s first sustained, controlled, heavier-than-air flight – more than two years before the Wrights.

Intrigued by Crouch’s reaction, Brown soon found himself rummaging through the attic of the Gustav Weisskopf Museum in Leutershausen, Germany. There he found a photo of the 1906 Aero Club of America exhibition, one of the first of its kind, and he noticed something in the background: photos on the wall of what appeared to be Whitehead machines. They were small and fuzzy, so he began some detective work. Brown asked the local police’s forensics team to blow up the images by 3,200%, which allowed him to identify what he believed to be Whitehead airplanes: one a triplane, another the 1901 airplane but grounded – and finally one more, the Whitehead No. 21 apparently off the ground.

Brown contacted the editors of Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft, an aviation reference guide founded in 1909 and often likened to an industry bible. Jane’s editor, Paul Jackson, grilled Brown for over an hour about his findings. Then Jackson stood up, shook Brown’s hand and told him he had just changed aviation history.

“I don’t think any aviation historian before or even after me is ever going to experience what I experienced,” Brown says. “Probably one of the greatest moments I’ve ever experienced in my life.”

An exhibition in January 1906 featuring what press reports at the time describe as photos—in red—of Whitehead’s 1901 powered monoplane.

In March 2013, Jane’s published its centennial edition (there were several years it didn’t publish during World War I and World War II) and its editor wrote a foreword describing how after all this time, it was Whitehead, not the Wrights, who was first. “The Wrights were right; but Whitehead was ahead,” he wrote.

Brown’s research and Jane’s declaration has triggered a war of words between Whitehead’s home state of Connecticut, which passed a resolution in June honoring the German immigrant as first in flight, and two odd aviation bedfellows in Ohio and North Carolina, two states considered the “Birthplace of Flight” and “First in Flight,” respectively, and often at odds over their claims to the Wright Brothers. In October, legislators from both states held a joint news conference disparaging Connecticut lawmakers while defending the Wrights’ legacy.

Without Jane’s involvement, Brown’s research and website – gustave-whitehead.com – would’ve likely been relegated to the far reaches of the Internet. With Jane’s on board, however, Brown appeared to have tipped history’s scales in favor of Whitehead for the first time. But a number of aviation historians and academics are lining up against Brown, including those at the Smithsonian, the longtime home of the Wright Flyer.

“When you get right down to it, to the Whitehead claim, there is – no – evidence,” says Crouch, the Smithsonian’s curator. “None.”

Born in Dayton, Ohio, where the Wright Brothers grew up and tested many of their planes, Crouch has been with the Smithsonian for almost four decades. He wrote a book chronicling the Wrights’ achievements as well as a history of aviation from kites to manned space flight. In 2000, President Bill Clinton appointed Crouch to the Chairmanship of the First Flight Centennial Federal Advisory Board.

Whitehead supporters often begin their argument with an article on Aug. 18, 1901 in the Bridgeport Herald, which showed a drawing of “Whitehead’s flying machine soaring above the trees.” In the months afterward, news of Whitehead’s feat made it into dozens of newspapers around the world. But Crouch says there was just one original story about the 1901 flight that was later picked up by other newspapers, and that one of the flight’s witnesses – James Dickie – later said the entire thing never happened.

“Throughout his life he always said, the story is a hoax. I wasn’t there. I didn’t see the airplane fly,” Crouch says. “He thought the article was based on Whitehead talking to the reporter about what his airplane would be capable of doing.”

There’s also a group of eyewitnesses who supposedly saw Whitehead fly and were later questioned, many under oath. Crouch says pro-Whitehead researchers interviewed them, raising the possibility that they used leading questions. He claims one witness was even paid to remember a Whitehead flight.

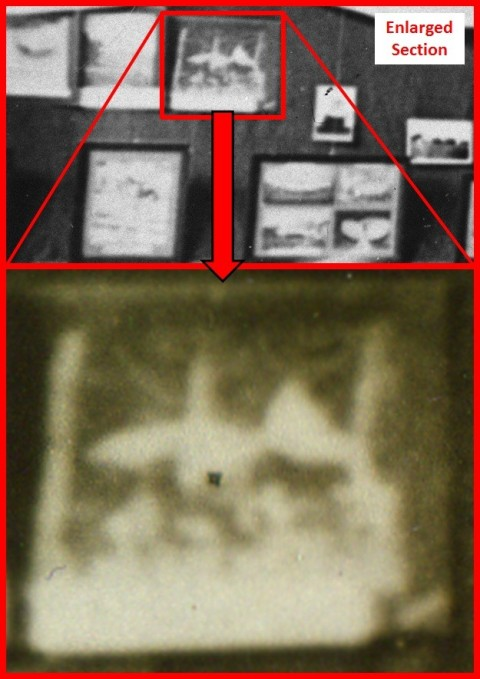

Brown believes the photo he analyzed corroborates reports from a Scientific American article from August 1906 about the Aero Club exhibition, which describes a “single blurred photograph of a large birdlike machine propelled by compressed air, and which was constructed by Whitehead in 1901.” The photo, the article says, was of a “motor-driven aeroplane in successful flight.”

An enlarged section of the exhibition photo appears to be Whitehead’s monoplane in flight, according to Brown’s analysis.

But Crouch is inclined to believe that the journalist mistook a photo of one of Whitehead’s gliders as a full-scale, motorized machine. Even so, he believes the photo is so grainy, it doesn’t prove anything.

“The picture that Brown found is nothing but a smudge,” Crouch says. A few dozen aviation historians agree and recently released a statement repudiating Brown’s findings, saying his arguments are based on a single flawed news article combined with questionable witness testimony gathered more than 30 years later.

Considering the issues many aviation historians have concerning the Whitehead claims, what would persuade the editor of Jane’s to make such a history-altering pronouncement? Crouch has a theory.

“Jane’s comes out every year like clockwork, and nobody ever pays any attention to it,” Crouch says. “This was the 100th anniversary. I would suggest that he might’ve been thinking something like, Gee, it would be nice to get some publicity for this.”

In 2009, Jackson — Jane’s editor — wrote a foreword praising the Wright Brothers for being first in flight but later realized that he had never really explored the first in flight claims. By the time the 100th issue of Jane’s came around, Brown’s research had convinced Jackson that Whitehead was first. Jackson says that the annual journal — used as an up-to-date reference guide for aviators — would never go off-topic into aviation history merely to sell copies.

“Nobody in their right mind buys it every year to discover anything about ancient airplanes,” Jackson says. “If we wanted to increase sales by making sensational claims about something, we would choose current and future aviation because that’s our core market. There’s an unlimited supply of such stories which can be whipped up. Why go off-topic by more than a century?”

Whitehead supporters also claim there’s an ulterior motive at work: the Smithsonian is protecting the Wrights.

After Orville Wright died in 1948, the executors of the Wright estate agreed to sell the 1903 Flyer to the Smithsonian on one condition: that the museum never say anyone else flew before the Wrights. (There have been other claimants to the record, such as aviator S.P. Langley.) If they did, the family would demand the Flyer back.

For years, the Wright Flyer has been one of the most popular exhibits at the National Air and Space Museum. About 7 million people visit the museum each year, and because the Wright Brothers exhibit is centrally located, museum officials say most visitors see it.

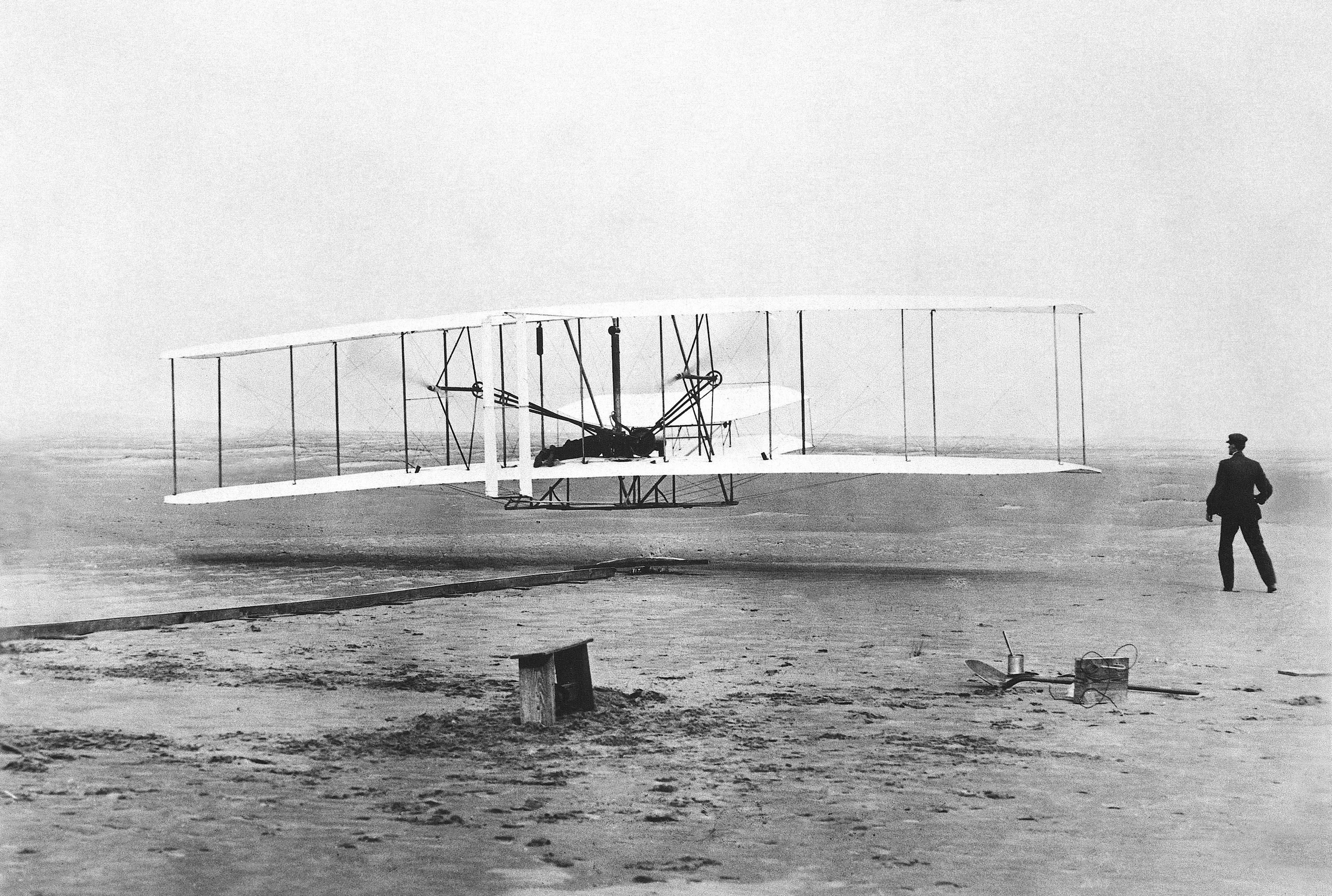

Orville Wright is at the controls of the “Wright Flyer” as his brother Wilbur Wright looks on during the plane’s first flight at Kitty Hawk, N.C. Dec. 17, 1903.

In the eyes of Whitehead supports, “the Contract” is one of the reasons we learn all about the Wrights and know virtually nothing of Whitehead. The Smithsonian, the believe, is defending the Wright Brothers in perpetuity so it can hang on to one of its most beloved exhibits. Crouch, however, doesn’t see it that way, and he says he doesn’t feel contractually obligated to defend the Wrights either.

“If anybody ever proved to me that somebody had flown before the Wright Brothers, I’d say so,” Crouch says. “I’m an honest scholar. I’ve spent 40 years thinking about this stuff. I’d tell the truth.”

The Wright fight would’ve likely stayed within the hangars and halls of the aviation community if it hadn’t been for a Connecticut bill passed into law in June, which literally wrote the Wright Brothers out of history in favor of Whitehead. Today, Connecticut honors Whitehead’s Aug. 14, 1901 flight as the first. The measure was part of a sweeping omnibus bill that included naming the ballroom polka as the state polka and “Beautiful Connecticut Waltz” as the second state song. For Republican State Sen. Mike McLachlan, who helped usher the bill through the Senate, the Smithsonian contract is what piqued his attention that maybe it wasn’t the Wrights after all.

“I never heard of history by contract,” he says. “That made me take pause on the whole topic.”

State Sen. Bill Cook of North Carolina, who participated in last month’s press conference defending the Wrights with State Rep. Rick Perales of Ohio, says when he first heard of the Connecticut law, he was inclined to ignore it.

“It’s like if somebody told you that, Oh, by the way, I believe that Ben Franklin was the first president,” he says. “I mean, it’s just stupid. When you’re arguing with an idiot, you become an idiot.” But Cook decided to weigh in on the matter once local media picked up the story.

In the 1980s, the last time the Whitehead claims experienced a brief moment of popularity, North Carolina passed a resolution stating that the Wright Brothers were first. Now in Ohio, Rep. Perales plans to introduce similar legislation refuting Connecticut’s claim.

Both states likely bring in tens of millions of dollars from their Wright Brothers-affiliated tourist sites, not to mention the money their substantial aerospace industries generate. In Outer Banks, N.C., 450,000 people visit the Wright Brothers National Memorial each year out of about 8 million annual tourists. Last year, the region brought in $900 million in tourism expenditures. In Dayton, Ohio, the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base has a work force of 29,000, and the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force brings in more than 1 million visitors each year.

“That’s the one pride we have about who we are and what we do,” Rep. Perales says. “It is in our fabric.”

As state legislators battle it out, Brown is back in Germany fighting a new war. He’s essentially trying to get Crouch fired. As he’s been digging into Whitehead’s past, he came across a letter Crouch wrote in 1987 casting doubt on the most famous Wright Brothers photo in existence, one showing what most believe to be the first Wright flight on Dec. 17, 1903. In the letter, Crouch says the flight in the photo was “probably not” sustained, meaning it only briefly became airborne. Crouch now says that yes, all four flights made that day were sustained and that he was trying to put the first flight in context of the other four, that each one was better than the one before it. But for Brown, his research has called into question the entire Wright Brothers narrative.

“The whole Wright thing for me now is really shaky,” he says. “I went to grade school like everybody else and learned the Wrights had invented the airplane. And it’s starting to look very different.”

But first only matters so much, something even Brown acknowledges. Aviation has changed the way we go on vacation, how we practice commerce and the ways in which we wage war. And those modern planes were largely built on the designs of the Wright Brothers, not Whitehead.

“I’m not an aviation historian that’s trying to say the Wrights did nothing and they’re insignificant,” he says. “My subject is not who developed the first practical airplane that changed the world. That was the Wrights, definitely. I’m not trying to take any of that away from them. They just weren’t first.”