VA Secretary Eric Shinseki

Officials with the Department of Veterans Affairs likely won’t acknowledge it publicly until later this year, but those responsible for processing disability claims believe the infamous “backlog” peaked more than two months ago.

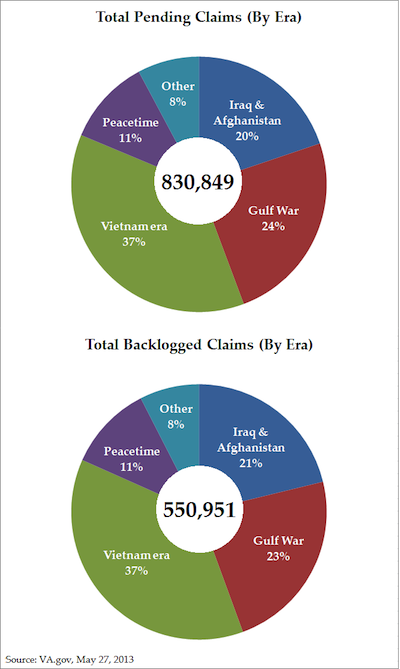

Last week, the total number of claims in the inventory fell to slightly more than 830,000—the lowest number since October 2011. Since late March, the backlog of claims has been on an eight-week slide as well. Last week, it too reached its lowest point since January 2012—nearly 17 months ago. The downward slope is now steeper than at any time during the Obama administration.

To be sure, no one is yet measuring the drapes in a backlog-free department—as it still stands at more than 500,000 claims. Nevertheless, the trend line is striking—and it mirrors what many VA employees are saying behind closed doors. Barring any surprises, the decline in backlogged claims will only accelerate as an automated system finally replaces paper processing over the next two years.

Therefore, it’s important to understand where the backlog actually stands in relation to where it was—and to fully recognize its context.

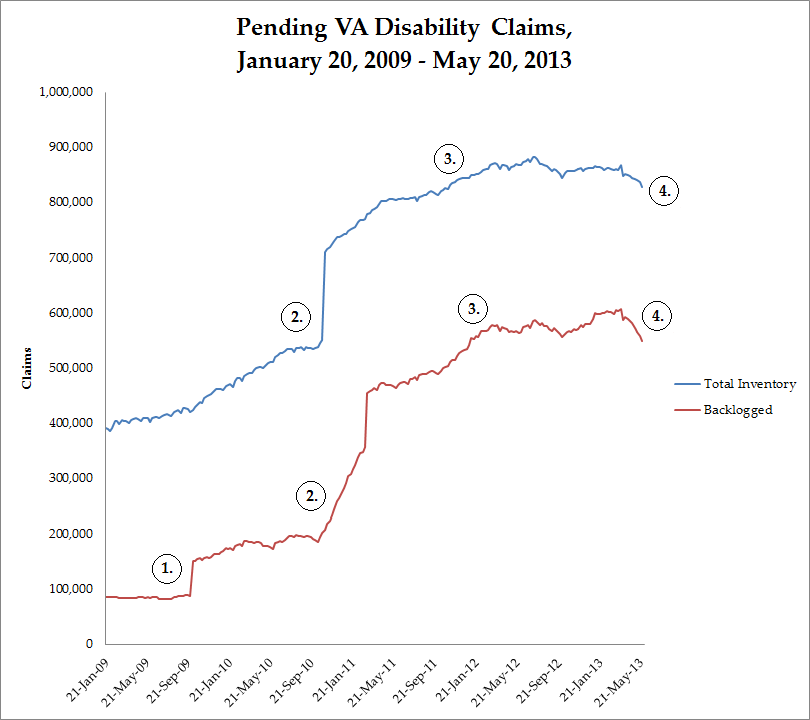

By using a simple chart to show the backlog since the beginning of the Obama Administration, we can get past the agenda-specific rhetoric and the media misconceptions to see how—and why—the backlog grew and how it began to shrink.

This chart illustrates the inventory of pending VA disability claims since January 2009. The blue line is all claims in the inventory—which peaked at 883,000 in July 2012. The moment a claim is received by the Department, it is included here.

The red line represents the portion of those claims that is backlogged—meaning (since October 2009) that they’ve been in the system for more than 125 days. The high-water mark for the backlog was in March 2013 at 608,000 claims.

Let’s take a look at what the chart shows.

1. The backlog initially expanded as a result of VA raising its own standards.

On the January afternoon Eric Shinseki took over as the nation’s seventh VA secretary, he inherited a mess.

To his immediate front, the former Army chief of staff faced a paper mountain of 391,127 separate disability claims—filed by veterans from every conflict since World War II. Nearly a quarter of the claims (more than 85,000) had been languishing in the system for more than six months.

The gravity of this situation in early 2009—with one war ending and another still raging—was not lost on the new boss. Compounding his problem, however, was the fact that he had little to work with in terms of a technological solution. VA was paper-bound, its IT system antiquated—and it had been this way for years.

Everyone knew this.

Unfortunately, the only way to fix the system was to allow it to get worse—for very specific reasons—before it would get better.

Therefore, the first sharp upward turn for the backlog during this period took place on October 1, 2009 when VA officially defined what “backlog” meant. Prior to that date, VA had categorized disability claims as being in the system for more or less than 180 days.

One of Shinseki’s first acts in addressing the backlog, then, was to recognize that 180 days was neither useful as a measurement, nor fair to veterans: VA had to turn around claims faster—and the department had to hold itself to a higher standard.

Therefore, the new standard for deciding a disability claim became 125 days. This administrative redefinition was good news for veterans. Essentially it was an acknowledgement by Shinseki that VA’s past performance wasn’t good enough—and it was a commitment to cut processing time, eventually, by nearly a third.

The bad news for VA—at least from a PR standpoint—was that it immediately added 62,000 claims to what then became known as the “backlog.” The 85,000 or so claims in the backlog pile nearby doubled to 150,000 overnight, putting it well into six figures for the first time.

Shinseki’s next two backlog-related decisions were just as necessary—but also were double-edged swords.

2. Expanding eligibility for veterans affected by PTSD and Agent Orange more than doubled the claims backlog.

As if the paper weren’t problem enough, Shinseki and his staff soon learned that thousands of Vietnam War veterans—many with whom he likely served—had been barred from claiming disability benefits for conditions related to their exposure to the toxic defoliant Agent Orange.

He also learned that when a veteran claimed post-traumatic stress related to time in combat, the veteran was obligated to prove that a specific stressor—an event at a certain time and place—had caused the condition. But because many returning veterans weren’t able to prove a specific instance had caused their sleepless nights, irritability, and hyper-vigilance, they were being denied disability benefits.

Shinseki was troubled by both of these. He viewed them as unfair and unjust. So he took action in late 2009, announcing expanded eligibility for those affected by both combat PTSD and Agent Orange.

For veteran groups and, more importantly, the veterans in those categories, it was a long-awaited victory. For the backlog, however, the impact was severe once VA began adjudicating these “presumptive” claims.

As evident in the chart above, the backlog more than doubled in size in less than four months following these changes—between November 2010 and March 2011. A backlog that had hovered around 200,000 claims in summer 2010 was suddenly brimming with more than 450,000 claims by spring 2011.

3. Improved VA outreach amid a difficult economy caused a steady, overall rise in disability claims—especially among aging Vietnam veterans.

It wasn’t just a simple redefinition and expanded eligibility, however, that swelled the claims backlog. In reality, beginning in late 2008, the weak economy hit older veterans hard. A year later, VA began a new era of outreach aimed at raising awareness of VA benefits in ways never before done.

That outreach—especially around Agent Orange—began bringing Vietnam veterans, many of whom had long ago given up on VA, back into the fold. And they were filing claims and enrolling in droves.

According to The Los Angeles Times:

Basic demographics explain some of the filing frenzy. Vietnam veterans are becoming senior citizens and more prone to health problems. Any condition they can link to their military service could qualify for monthly payments — and for many illnesses, it is easier for Vietnam veterans than other former troops to establish those links.

Heart disease, Type 2 diabetes and several other illnesses common in older Americans are presumed to be service-related for Vietnam veterans because the government determined that anyone who served on the ground was likely to have been exposed to Agent Orange. The herbicide is known to increase the risk of those conditions.

At the same time, changing attitudes toward mental health care mean that veterans suffering from PTSD and other psychiatric conditions now are more willing to come forward. The uncertainties of older age — and possibly the decade-long spectacle of the current wars — may be triggering relapses of PTSD among some veterans.

And herein lies perhaps the biggest fallacy of the VA claims backlog as portrayed in the media. The myth is that the VA claims backlog has much to do with veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan—that it is, for the most part, related to a crush of returning war veterans.

This myth is perpetuated by interest groups like Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America (IAVA) and echoed by many in the media. For example a pre-Memorial Day Miami Herald editorial is representative of the pervasive misinformation floating in the media. It discusses the VA backlog almost solely in terms of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans—even though 80% of backlogged claims belong to veterans of other eras.

Understandably, the VA has been overwhelmed. The global war on terrorism and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have required the services of millions of Americans, many of whom have been obliged to make repeated tours of duty in combat zones.

Over the past 12 years, about 2.5 million members of the Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, Coast Guard and related Reserve and National Guard units have been deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq, according to Department of Defense data. Of those, more than a third were deployed more than once. Nearly 37,000 have been deployed more than five times, and 400,000 service members have reportedly done three or more deployments.

The editorial continues with more of the same.

In fact, claims filed by Iraq and Afghanistan veterans are only a small portion of VA’s inventory and backlog. Currently, they make up 20% of VA’s pending inventory. They represent 21% of the backlog. Only 10% of first-time claims in the backlog belong to Iraq or Afghanistan veterans.

This is crucial to understand because it demonstrates that Iraq and Afghanistan veterans are not central to this problem.

VA’s actions since 2009—not coincidentally under the leadership of a Vietnam veteran—have, in fact, revealed the extent of the longstanding estrangement between Vietnam veterans and the government which sent them to war nearly 50 years ago.

And after four years of concerted outreach, along with special care taken to bring Vietnam veterans back into the fold, the awareness campaign has paid off.

Former secretary of state and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell—himself a Vietnam veteran—even noted recently that “the rate of claims being submitted” is “rather extraordinary and unexpected.” Thirty-eight years after the end of the Vietnam War, it seems, its veterans are coming home to the care they have always deserved.

Unfortunately, the system wasn’t designed to handle such an influx. And that leads us to the fix for the backlog of VA claims.

4. The backlog is shrinking, not growing.

As Bob Wallace, the executive director of the Veterans of Foreign Wars Washington office, recently told The New York Times: “The backlog has been a problem for years. . .but fixing it is not going to happen overnight.”

Shinseki and his staff at VA knew this. That’s why, in January 2010, VA began to conceive of plans to automate the claims process. Planning for a fully electronic system was complete by June 2010 and the Veterans Benefits Management System, or VBMS, was well on its way to becoming a reality.

The process of planning, procuring, pilot testing, and deploying in limited areas took nearly three years. But by December 2012, VA was fielding VBMS department-wide.

By May 2013, the system was in more than 90% of VA regional offices.

At this point, VBMS is still a work in progress, and the IT infrastructure on which it is built is still not completely renovated. But there is no doubt it is coming online.

When we look at the sharp decline in the backlog over the past two months, however, what we’re seeing, primarily, is the effect of VA’s decision in April to “make provisional decisions on the oldest claims in inventory”—a wise decision, but one that removes those claims from the backlog before every one is resolved completely. While this speeds the process considerably, it’s assumed that some of those claims will ultimately end up back in the backlog—though many, if not most, will not.

This decision, along with mandatory overtime this summer, will hold the backlog in check until VBMS is fully functional in 2014.

And that brings us to where we are now.

The VA backlog is a complicated topic. As a political football, it has divided veterans groups, pitting veteran advocates unnecessarily against each other. It has caused many well-meaning—but uninformed—journalists to muddy the waters even further. Politicians and pundits have criticized VA ceaselessly on the issue.

Therefore, as VA’s long-standing plan takes effect this year, and the backlog recedes, it’s more important than ever to remember that misleading or inaccurate information helps no one.

Brandon Friedman is a vice president at FleishmanHillard in Washington, D.C. and the author of The War I Always Wanted. From 2009 to 2012, he worked at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Follow him on Twitter at @BFriedmanDC.