The SS United States, docked at Pier 82 in South Philadelphia. The ocean liner and troop transport was the largest passenger ship built in the United States. There is currently a campaign to restore it and turn it into a floating museum.

Just off of Interstate 95 in South Philadelphia, the giant red, white and blue stacks of the SS United States can be seen above an unmarked pier, just across the road from an Ikea superstore. On first glance, she appears shorter and sleeker than modern cruise ships, and where the paint has chipped away, oxidized metal gives off a splotchy, rust color that can be seen from well beyond the roadway.

The only way onto the ship at the moment is up a steep gangplank into one of the middle decks, a dark passageway that looks well suited for the set of a horror film. On the upper decks, the walls have been stripped to the yellow primer; the long walkways where the biggest stars of the day once strolled are a dull granite-grey, flanked by cracked windows and doors permanently ajar.

The SS United States, docked at Pier 82 in South Philadelphia.

This current state is a blunt contrast to the two decades when the United States was the most luxurious ocean liner and fastest troop transport in the world. She once smashed speed records; ferried presidents, kings and movie stars; and graced the pages of magazines and newspapers all over the country. A decade before space flight captivated imaginations, the “Big U” as she was called, was the height of technological innovation, a large-P Public/private partnership meant to make money in times of peace and serve the country in times of war. Then long before the end of her tenure, she was taken out of service and largely forgotten. A dedicated group trying to save the United States has raised more than $1 million, but it’s now putting out what may be the ship’s final distress call, asking donors with deep pockets to help buy some time before the ship is lost for good.

If there was ever a monument to America’s nautical glory, it would surely be the USS Constitution. Named by George Washington after the founding document of the Republic, she earned the nickname “Old Ironsides” after defeating four English warships during the War of 1812. Yet despite her heroics, when the Constitution reached her 31st year of service, the estimated costs to keep her afloat were estimated at more than $150,000 (about $3.2 million today).

An article in a Boston newspaper claimed that the Constitution was destined for the scrap yard and prompted physician and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes to pen the poem “Old Ironsides”:

Ay, tear her tattered ensign down!

Long has it waved on high,

And many an eye has danced to see

That banner in the sky;

Beneath it rung the battle shout,

And burst the cannon’s roar;–

The meteor of the ocean air

Shall sweep the clouds no more.

Though reports of the Constitution’s demise had been exaggerated, those words incited a public uproar, and the Navy agreed to foot the bill for the ship’s repair.

Since the country’s earliest days, Americans have been building big things–from ships to secure our waterways to skyscrapers to house our businesses to planes and shuttles to explore the heavens. And going all the way back to the early 19th century, there has been controversy over what to do with those articles when they were no longer needed. Some, like the Constitution became floating museums, while many, like her sister ship, the USS Congress, were broken up and sold piece-by-piece. That fate seemed like a certainty for the United States in the late 20th century, as changing times and creditors conspired to scuttle one of the final monuments of an era when people were connected, not by digital devices or jets in the sky, but by ships steaming on the sea.

Like many grand endeavors, the United States was willed into existence by the nearly fanatical efforts of a brilliant man who could have been called the Steve Jobs of shipbuilding; if popular memory weren’t so short, perhaps Jobs might have been called the William Francis Gibbs of consumer electronics. A lawyer by training who flunked out of Harvard because he spent more time poring over British nautical blueprints than on his engineering studies, Gibbs had harbored the dream of creating ocean liners after watching ships launch as a young boy. At the behest of his parents he earned a law degree from Columbia, then after unhappily practicing law for two years, he quit with the goal of designing the fastest ocean liner in the world.

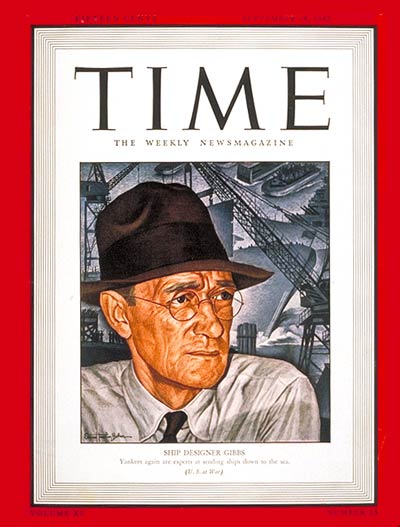

William Francis Gibbs on the Sept. 28, 1942 cover of TIME.

Gibbs became one of America’s foremost ship designers and rose to national fame during World War II. His firm, Gibbs & Cox, designed 70% of the Naval ships built for the war effort, everything from destroyers to landing craft to Liberty ships. He oversaw an operation that turned out nearly 10,000 blueprints each day, landing him on the cover of TIME in 1942, when the magazine crowned him “the top U.S. Naval architect and marine engineer.”

After the war, as shipbuilders once again turned to peacetime travel, Gibbs finally built his dream ship: the 990-ft long S.S. United States. The government kicked in two-thirds of the $78 million price tag, and the military sprinkled the ship with classified designs. In return, the Defense Department had the right to use her as a troop transport in the event of another major war. In 1952, the United States was capable of moving an entire Army division–14,000 men–halfway around the world without stopping. “Because of its long, slim prow, the United States is racier-looking than most ocean liners,” TIME wrote of her sleek design in a June 1952 cover story on the ship’s launch.

The Big U had two different engine rooms so the ship could steam even if one was taken out by a torpedo, and her four propellers generated enough power for a city the size of San Antonio. To prevent fire, the only wood on board was the butcher’s blocks and pianos; nearly everything else was made of fire-retardant material. About the only decorative piece on the ship’s exterior were two huge red, white and blue stacks–at the time, the largest in the world–which weren’t necessary for the engines but were designed to be in proportion with the giant hull.

Until the summer of 1952, the fastest ship in the world was the Queen Mary, which had held the trans-Atlantic record for 14 years. On July 3, the United States steamed out of New York; 3 days, 10 hours and 40 minutes later, she passed Bishops Rock, England, besting the Queen Mary’s transatlantic speed record by nearly half a day. On the way back, the ship also blasted the westbound record to win the Blue Ribband, the accolade given to the fastest passenger liner in the Atlantic. “The war was over, and it was a tremendous event in prestige for the United States,” says Albert Herberger, who served as a cadet-midshipman aboard the United States and later became a Navy admiral and head of the U.S. Maritime Administration. “This was a way for Uncle Sam to get some recognition for a peaceful event that caught everybody’s imagination.”

For the next 17 years, the United States carried more than 1 million people across the Atlantic on bi-weekly runs to England, France and Germany. The Department of Defense sent military families stationed in Europe on board the Big U. Then in the late 60s, the jet became the fashionable way to the Continent, and the Army scrapped plans to transport troops by ship. Space travel launched a new era where people turned aspirations to the skies instead of the sea. Government subsidies, which accounted for more than half of the operating budget, ran out, and the Big U was finished.

After she was removed from service in November 1969, the United States changed hands several times, and by 2010, unable to pay the docking fees, the ship was bound for the scrapyard. Then at a dramatically late hour, Philadelphia philanthropist H.F. “Gerry” Lenfest pledged $5.8 million, allowing a group called the SS United States Conservancy to try and save the ship from the scrapyards.

The woman at the helm of the conservancy has a familiar name and a deep connection to the United States: Susan Gibbs, the granddaughter of the ship’s designer. “This was in the post-war period when the nation was feeling very confident, the sky was the limit,” Gibbs says of the Big U’s era. “The ship really was technologically innovative and rewrote the rules of what a ship could do and could be.”

The conservancy’s ideas for the ship include creating a floating hotel like the Queen Mary, and perhaps include offices or an incubator space, although a closer model is the USS Intrepid. A preserved aircraft carrier, the Intrepid is also a floating air and space museum, telling a story larger than the vessel itself. The conservancy wants a similar focus for the United States. “We want to preserve the ship and share a really important story…but we want to use the ship as a way to advance and promote innovation in the 21st century,” Gibbs says. “We want to help inspire new discoveries, new technologies, new creativity. We’re connecting the past, the present obviously, but more importantly the future.”

Through a social-media campaign, the conservancy raised more than $1 million and has been in talks with developers about turning the ship into a destination like the Intrepid. But the cost of keeping the United States afloat runs about $80,000 a month, and the group needs other generous donors like Lenfest to help buy more time. So they’re putting out a call for donations before they run out of time and the ship is lost to the scrapyards forever.

Given the right location and project, the conservancy hopes the United States could become a popular attraction, serving as a monument to the age when ocean liners connected the far ends of the world. The only certainty when it comes to aging treasures, as Oliver Wendell Holmes knew, is that once their ensigns are tattered down, they are gone forever.

It is a fact we should keep in mind when we choose which parts of our history to save, and which ones we must let go.