Sometimes, the doctors will tell you what the politicians won’t.

That’s the bottom line in a new Pentagon assessment of the human costs of the nation’s post-9/11 wars, which shows mental casualties growing far more rapidly than any kind of physical wound – along with a warning that the nation has only begun paying the costs of such injuries.

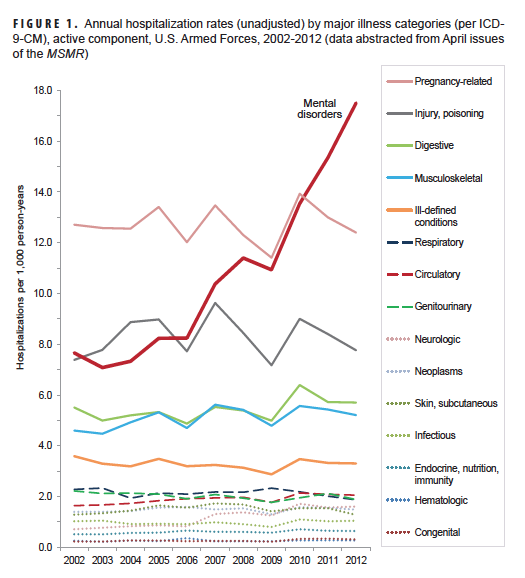

The April edition of the Medical Surveillance Monthly Report is the latest in a long series of bleak studies from the Pentagon medical community charting the hidden costs of the nation’s recent wars. It notes that the hospitalization rate for mental disorders among active-duty military personnel, for example, grew by 8% from 2002 to 2006, but more than doubled from 2006 to 2012. These reports tend to be unheralded, and aren’t rolled out with press briefings, or even press releases. Instead, they’re written for military medical professionals and quietly issued to guide their efforts in patient care and research.

“This report documents continuous increases in health care burdens associated with certain psychological and physical (but not combat trauma-related) disorders beginning approximately five years after the start of the Afghanistan/Iraq wars,” it says. “To the extent that some adverse health effects of prolonged periods of war fighting may be persistent and resistant to treatment, medical care may be needed by large numbers of war veterans long after war fighting ends.”

The Pentagon’s Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center published the report on Wednesday. It continues a tradition of not sugar-coating war’s painful residue with an editorial entitled Signature Scars of the Long War:

Many U.S. casualties in Afghanistan and Iraq have resulted from rocket and mortar attacks, detonations of land mines, ambushes of convoys and patrols, and sniper attacks. In turn, many war veterans suffer from the clinical sequelae of traumatic brain injuries (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). TBI and PTSD are now often referred to as the “signature wounds” of the Iraq/Afghanistan wars. In addition to TBI and PTSD, however, diverse other physical and psychological disorders have been associated with repeated or lengthy wartime deployments. These conditions include disorders of the neck, back (e.g., intervertebral disc disorders), and other joints; hearing loss, alcohol and drug abuse, organic sleep disorders, headache, chronic sinusitis, skin conditions, and various “ill-defined” conditions.

Retired Army colonel Elspeth “Cam” Ritchie finds the chart above “alarming, but not surprising to those in the military medical-mental health community.” The Army’s Mental Health Advisory Teams have been reporting such data up the chain of command for nearly a decade, says Ritchie, a regular Battleland contributor. “When President Bush was in office,” she adds, “it was harder to openly discuss these issues.”

The Pentagon’s health surveyors reviewed 16 different illness/injury categories from 2003 to 2012. “For 15 of the 16 illness/injury categories of interest, annual hospitalization rates remained fairly stable, with some year-to-year variability, throughout the 11-year war period,” the editorial notes. “However, for mental disorders, annual hospitalization rates were fairly stable from 2002 through 2006 and then sharply increased from 2006 through 2012.”

Rebecca Townsend is a psychologist in private practice who often deals with soldiers from nearby Fort Campbell, Ky. She says the report is “almost refreshing” to have the Pentagon’s medical corps “support, with data, what providers have felt in their offices for years.” Soldiers, she says, increasingly not only need the kind of help she offers, but are willing to seek it. “We, as a nation, must begin to take responsibility for the healing of our elite population of warriors,” she adds.

The study cautions that battlefield wounds may manifest themselves long after combat is over:

If there are cumulative health effects of continuous exposure of a military force to the stresses of war fighting, the first clinical manifestations – e.g., mental disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, sleep disorders, ill-defined conditions — may not be apparent until several years after war fighting begins. If so, the short and long-term health care costs associated with “short wars” would be much less than those associated with long wars.

“We are on unfamiliar ground here,” says Robert Scales, a retired Army major general and military historian. “No western country in this century has ever done two wars in a decade using just regulars.”

Among the report’s findings:

— Mental disorders [in 2012] accounted for more hospital bed days…than any other morbidity category and nearly half (49.6%) of all hospital bed days overall…Mental disorders also accounted for the most lost work time…26.0% of the total.

— In 2012, mood disorders and substance abuse accounted for nearly one-third (31.2%) of all hospital days. Together, four mental disorders (substance abuse, mood, anxiety, and adjustment reaction) and one pregnancy and delivery-related condition accounted for over one-half (53.9%) of all hospital bed days.

— In contrast to 2008, in 2010 and 2012 there were more hospitalizations for mental disorders than for any other major diagnostic category.

— In 2012, mental disorders accounted for more hospitalizations of U.S. service members than any other major diagnostic category.

— Adjustment reactions (including post-traumatic stress disorder) and episodic mood disorders were associated with more hospitalizations among active component members than any other specific condition…together, these two conditions accounted for 18% and 20% of all hospitalizations of males and females (excluding pregnancy/delivery), respectively.

— Among members of the Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard, pregnancy and delivery-related conditions accounted for more hospitalizations than any other category of illnesses or injuries; however, among members of the Army and Marine Corps, mental disorders were the leading cause of hospitalizations. The crude hospitalization rate for mental disorders in the Army (28.1 per 1,000 person-years) was more than double that in the other Services.

— The recent sharp increase in hospitalizations for mental disorders likely reflects the effects of many factors including repeated deployments and prolonged exposures to combat stresses; increased awareness and concern regarding threats to mental health among unit commanders and other front line supervisors, service members and their families, and medical care providers; increased screening for and detection of mental disorders after combat-related service and other traumatizing experiences; and decreasing stigmas and removal of barriers to seeking and receiving mental disorder diagnoses and care.

— In the past five years, the distribution of illness- and injury-related ambulatory visits in relation to their reported primary causes has remained fairly stable. Of note, however, from 2008 to 2012, the numbers of visits that were documented with diagnostic codes indicating mental disorders increased 71.2%. Thus, in 2012, mental disorders accounted for approximately 19% of all illness- and injury-related diagnoses reported on standardized records of ambulatory encounters.

The unsigned editorial that accompanies the report suggests the wars could have an unwelcome legacy: “Someday persistence of anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, neck, back, and joint pains, headache, and various `ill-defined’ conditions among Afghanistan/Iraq war veterans may be recognized as signature scars of the long war.”

All this is, pure and simple, the legacy of turnstile deployments, where troops would return to war zones repeatedly for a decade or more. It became clear years ago that mental-health ailments rose with repeat deployments.

But rather than resurrecting a draft and sending fresh troops to war for a single tour, the nation elected to tap into its reserve forces and basically make them part of the operational force. But even that increase – which essentially has doubled the size of the operational Army – subjected many thousands to repeated combat tours.

Politically, if you were a lawmaker, it was a smart move.

Medically and mentally, if you wore your nation’s uniform, not so much.