A solider monitors the flow of information into a tactical operations center, or TOC.

The tactical operations center is, as most ground-pounders like me know, the brains of a battalion or a brigade.

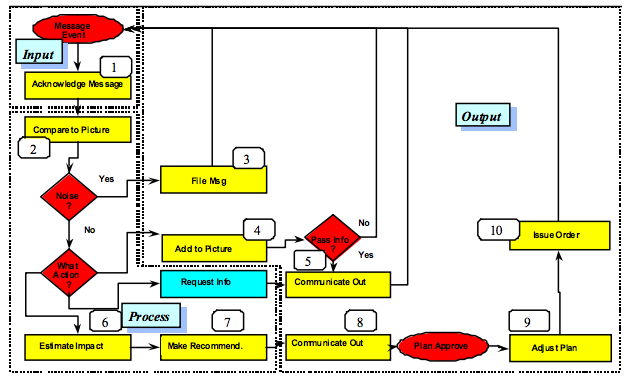

Information flows in from a million sources, and decisions resulting in actions flow outward. As a young lieutenant you think of the TOC — pronounced “tock” — as alien territory, host to unfamiliar creatures with arcane motivations.

Eventually you learn better, and you figure out that the most critical elements inside that headquarters are patience and wisdom. I should note that it is the latter element that leads to the former. This is a basic statement which applies to infantrymen like me, but any grunt, jarhead, wingnut or squid, of any rank, should grok these basic precepts.

The bottom line is that if the collective personality of the TOC has those two attributes, you win. If it does not, you lose. It does not get much simpler than this binary statement.

But there is more to this than meets the eye, because you really can learn something about living as a thinking citizen in a representative democracy which has a free press…just by learning this lesson from the TOC.

Significantly, it is those two essential elements that I mentioned, wisdom and patience, which are exactly what we need as citizens to understand the news during breaking events. OK, now you are reading this and saying, “Well yea, duh.” Bear with me for a second, because I have evidence that this is not always the case within our national dialogue, regardless of how “common sense” it seems.

So let us look, briefly, at three cases: Benghazi; the death of a young diplomat in Afghanistan; and the events in Boston this week.

When events unfolded in Libya in September of last year, the news on the ground and the news from Europe and the news from Washington, DC, was not synchronized.

Stories at the outset were confused, and the reporting from what had become a combat zone was also confused within military and diplomatic channels. Press officers reported what they had been told, hour by hour, but those sending information to the press officers, often from hundreds and even thousands of miles away, did not know what was happening on the ground, at that instant.

This meant that “news” given to reporters was actually only “unsubstantiated reports”? Why, because let’s face it, a lone untrained-in-reporting civil servant in a foreign country, reporting remotely, based upon what he is hearing second-hand, is not exactly the same thing as a cavalry scout or SF strategic recon elements, now is it?

In the chaos of the moment that untrained-in-skepticism junior diplomat is doing what he thinks is right, he is forwarding to the media what he believes to be “the truth.” But what he is really doing is forwarding random observations, some of them wrong, without understanding. This happens, for example, with junior Scout Platoon leaders as well. At least until we old cranky guys beat it out of them.

But here is where your lesson from the TOC comes in.

Every battalion commander worth an ounce of salt tries to teach his young officers, “Never trust the first reports.”

It is an adage well worth acknowledging. The first report from your troops on the ground is chaotic, often incoherent, and riddled with “facts” that are not, actually, factual.

Anybody who has been shot at knows this. On the two-way rifle range some inexplicable things happen. Time, for example, gets longer or shorter. Distances too are distorted, becoming closer or further away. And all of that often depends upon the volume of incoming that you are taking.

A wise boss, a good battalion or company commander, knows this. He allows for this, and waits.

He asks for clarifications, in small bites, as possible. He knows about the distortions, and he knows that the distortions will be corrected when things smooth out and people can look over the parapet.

What happened in America, in response to Benghazi, was a classic case of a toxic leader receiving information, and reacting in the way that toxic leaders often do, by assigning blame before they understand the situation, and by ascribing the changing descriptions of what happened to a conspiracy, not the reality of war as we common-sense soldiers understand it.

[Interesting Historical Sidebar: the bombardment by Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia against the defenses of the Union Army of the Potomac on the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg lasted, roughly, from 13:00 to 15:00 that day. A huge number of soldiers wrote, at the time or later, about their experiences of that period. The estimates of the total duration of the bombardment range from 20 minutes to four hours. Surprising nobody at all who has been shot at, the estimate of four hours was from a Union infantryman at the point of impact. The guess of 20 minutes was from a very busy Confederate artilleryman. Of course, if you only examine some sources, you could conclude that there is a conspiracy to (increase)(decrease) the period of the bombardment, based exclusively upon “eyewitnesses.”]

Already we are seeing signs of similar impatience and a lack of consideration (by which I mean intellectual consideration, not politeness) in both the case of the death of the junior State Department diplomat in Afghanistan last week and the bombing in Boston this week.

Here is the bottom line.

If you take this with you and teach it to all of your friends, our experiment in representative democracy will be the better for it. Generally speaking, pay attention to the reporter on the ground, but do not pay attention to the talking head who fills the rest of the airtime.

The reporter on the ground is like a well-trained scout. He tells you specific facts, as they are known, and very little more. These are your nuggets, and just as you would treat the reports of scouts, use them as points of data, knowing that you need to assemble many such to approach understanding. Just like a battalion commander has to do in his TOC.

Sure, this is a lesson from the infantry, but also from the cavalry, the engineers, the tankers and for that matter, the pilots: never, ever, ever, trust the first reports. Those who send the first reports may mean well, but they are caught in the emotion of the moment, and the place, and the situation. Never, ever, ever, trust the first reports.

Look, think of it this way: The people who send the first reports, be they cavalry scouts or Reuters reporters, will send what they see, but they will also be tempted to send what they think. Watch out for that, from both of them. It is not because they are bad, or have a motive. It is merely because they are too close, in time or space, to accurately send anything but the most basic information. They, and you, need distance to think. So, are we clear? If not, let me say it one more time.

Never, ever, ever, trust the first reports. Journalists, like our recon scouts, see things and report them. Some in both professions, sometimes accidentally ascribe meaning to what they see. That is wrong. Sit back, listen to all of your scouts, and all of the journalists, and then, have the wisdom to act slowly and assemble a picture of who, did what, where and when, to whom, and why.

Teach you civilian friends this ageless military wisdom about deciphering reports, and we’ll have fewer conspiracy theories and, I submit, a better informed population.

Lieut. Colonel Bateman is a U.S. Army strategist serving with NATO forces in England. He has done combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. None of these comments necessarily represent the views of the United States Government, the Department of Defense or the U.S. Army. He can be reached at R_Bateman_LTC@hotmail.com.