Military airplane accidents are always scary. Initial reports often read like this:

Colonel Clay Garrison of the 144th Fighter Wing says Thursday afternoon [Dec. 27] at 3:35 while on a routine mission the pilot encountered trouble at 12–thousand feet. “When the aircraft malfunctions he tries to save the airplane. When that’s not possible he saves himself. It appears all the systems in the plane worked correctly because he reached the ground safely.”…The pilot who ejected safely is a seasoned veteran with more than 10–years experience with the F–16.

But ultimately Air Force investigators look into such crashes, and what they find can differ considerably from a commander’s initial impression.

The Air National Guard pilot involved in that California crash nearly four months ago didn’t “encounter trouble” – he made it happen, according to the official investigation into the crash, headed by Air National Guard Colonel Nathan B. Alholinna and issued last week. The pilot’s name was not released.

In nearly four decades of reading such reports, Battleland is hard-pressed to recall one where the pilot so willingly flew himself into trouble without the skill to get out of it. He flouted regulations, ignored repeated audible warnings, and fastened his lap belt so loosely that he ended up smacking his head on the the inside of the canopy, making it tougher for for him to try to save the $21 million aircraft his actions had doomed.

What follows are excerpts, in order, from the investigation, with emphasis added and most abbreviations, citations and references deleted:

On 27 December 2012, at approximately 1533 local time, the mishap aircraft, an F-16C Fighting Falcon, tail number 87-0315 assigned to the 144th Fighter Wing, Fresno Air National Guard Base, California went out of control during a training mission and impacted the ground 84 nautical miles east of Fresno, CA. The mishap pilot ejected safely with minor injuries. The mishap aircraft was destroyed upon impact with total loss valued at $21,405,503.25. The aircraft impacted the ground in a desolate area on government land causing superficial landscape damage. There was no damage to private property and there were no civilian casualties…

Complacency is a factor when the individual’s state of reduced conscious attention due to an attitude of overconfidence, undermotivation or the sense that others “have the situation under control” leads to an unsafe situation.

There is evidence that a high level of complacency existed for both the mishap pilot and the mishap wingman throughout the mishap sortie planning, briefing and execution. Mishap pilot testimony stated little mission planning time was available, required, or dedicated to the mishap sortie. While a combined motherhood and coordination brief occurred, the separate mishap flight brief was lacking in detail and did not cover critical basic fighter maneuver-specific training rules or include any basic fighter maneuver tactical discussion. Additionally, there appeared to be little to no discussion with regard to basic fighter maneuver setups, desired learning objectives, designated training aids/limitations, low speed warning tones, and basic operating limitations with regard to configuration. This is evident during the three basic fighter maneuver engagements when the mishap pilot was forced to audible directions to the mishap wingman multiple times regarding position, altitude, and setups. The mishap pilot referenced the simple nature of the mission and the frequency of similar missions as justification for the minimal planning, and while all required items were completed, this highlighted complacency in mission preparation.

The Head-Up Display tape revealed multiple examples of complacency. After taxi, the mishap pilot elected to take off six minutes early with a known corrupt navigation system…

The mishap sortie consisted of three basic fighter maneuver sets. The two High Aspect Basic Fighter Maneuver sets started from inconsistent and nonstandard parameters. There were several variances in starting parameters apparent on the HUD video with regard to the Basic Fighter Maneuver setups (approximately 50 knots in airspeeds, 7,000 ft. in altitude, and 2 nautical miles in separation). Additionally, the mishap pilot attempted three separate over the top maneuvers during the second and third Basic Fighter Maneuver sets with setup airspeeds of 278, 260, and 241 knots. During these maneuvers, the mishap pilot activated and remained within the low speed warning tone for approximately eight to 12 seconds, demonstrating little urgency to correct the low speed condition…

Pressing is a factor when the individual knowingly commits to a course of action that presses them and/or their equipment beyond reasonable limits…

…maximum maneuvering in a low speed state, especially maximum roll coupled with maximum aft stick, significantly predisposes the aircraft to departure…

The mishap pilot attempted three over the top (vertical loop) maneuvers during the second and third basic flight maneuver sets. During the initial maneuver of the second Basic Fighter Maneuver set, as exhibited in the unclassified HUD tape, the mishap pilot completed a 278 knot setup with continuous activation of the low speed warning tone for approximately eight seconds without a TERMINATE/KNOCK IT OFF. During the second maneuver of the second set, the MP completed a 260 knot setup with continuous activation of the low speed warning tone for approximately 12 seconds without a TERMINATE/KIO. During the final setup that led to departure, the mishap pilot reached a maximum airspeed of 241 knots and continuously activated the low speed warning tone for approximately 10 seconds without a TERMINATE/KIO. This low speed state coupled with inappropriate/aggressive recovery maneuvers, as discussed below, predisposed the mishap aircraft to an uncontrolled departure.

These instances of progressively borderline starting airspeeds for over the top maneuvers, excessive time spent within the low speed warning tone with little urgency to terminate or recover, and aggressive maneuvering in a low speed state indicated a tendency of pressing beyond reasonable limits. This tendency ultimately placed the mishap aircraft in a position where departure [from controlled flight] was imminent…

Procedural Error is a factor when a procedure is accomplished in the wrong sequence or using the wrong technique or when the wrong control or switch is used. This also captures errors in navigation, calculation or operation of automated systems.

Procedural errors occurred during two critical phases of the mishap sortie, the low speed warning tone recovery and the Out-of-Control Recovery. Technical Order 1F-F16C-1, section six, states to avoid a departure, specific control techniques are required. A pilot should first release aft stick pressure to reduce angle of attack and then smoothly roll inverted to the nearest horizon. After completing the roll, the pilot should smoothly apply aft stick pressure as required to keep the nose tracking towards the horizon. All pilot testimony, to include the mishap pilot, agreed that upon activating the low speed warning tone, the pilot should take immediate action to alleviate the condition, in accordance with the techniques described in the Technical Order guidance. The mishap pilot testified that upon hearing the low airspeed warning tone, he proceeded to recover the mishap aircraft. The Crash Survivable Flight Data Recorder data showed maximum aft stick continued upon activation of the low speed warning tone while adding maximum left roll. This unsuccessful recovery technique was not in accordance with Technical Order 1F-F16C-1. The mishap aircraft subsequently departed controlled flight.

Out-of-Control Recoveries are detailed in section three of Technical Order 1F-F16C-1. Successful recoveries require Critical Action Procedures per Air Force Instruction 11-2F-16, Volume 3. The Air Force Instruction directs pilots to immediately accomplish the procedures in the published sequence without reference to the checklist. These include (1) controls release (2) throttle idle (3) rudder opposite yaw direction (4) Manual Pitch Override switch override and hold with (5) forward and aft cycling of the stick in phase with nose oscillation. Technical Order guidance further states any deviations or delay could reduce effectiveness of the recovery and therefore delay recovery.

The mishap pilot correctly accomplished steps one, two and four as required. The third step was omitted due to contributing factors discussed below. Proper pitch rocking, step five, is accomplished by allowing the nose to lead stick motion and maintaining full stick inputs until the maximum pitch attitudes are reached. Data analysis reflects the mishap pilot pitch inputs were not held to maximum values or for sufficient duration. Additionally, these mishap pilot pitch inputs were not performed in phase with pitch cycles. These inputs are clearly illustrated in the Comparison of Recovery Inputs Figure of the 416 Flight Test Squadron mishap analysis…According to the 416 Flight Test Squadron analysis, “Comparison of the mishap pilot technique and proper technique show that aerodynamic recovery was unlikely to occur since the insufficient duration and magnitude of commands did not result in sufficient trailing edge down deflection of the horizontal tail at any point”…

Violation – Lack of Discipline is a factor when an individual, crew or team intentionally violates procedures or policies without cause or need. These violations are unusual or isolated to specific individuals rather than larger groups. There is no evidence of these violations being condoned by leadership.

As described within the human factors of Complacency, Pressing and Procedural Error, there were several violations of Air Force Instructions, Training Rules, and Technical Orders within the mishap sortie. The Aircraft Investigation Board found evidence the mishap pilot intentionally violated these regulations without cause or need. There is no indication the mishap pilot was unaware or unfamiliar with any rules or regulations. There is also no evidence to suggest a lack of experience given the mishap pilot had more than 2000 flying hours and was a highly experienced four-ship flight lead.

The mishap pilot knowingly and intentionally took off with an inaccurate navigation system with a positional error in excess of 100 nautical miles. This was in direct violation of AFI 11-2F-16, Volume 3, paragraph 7.1.1: “Do not accept an aircraft for flight with a malfunction which is addressed in the emergency/abnormal procedures section of the flight manual until appropriate corrective actions have been accomplished.” Additionally, 144 FW In-Flight Guide, page 2-13, lists the Inertial Navigation System on the Mission Essential Subsystem List. This was without cause or need, especially considering that the mishap pilot took off six minutes ahead of schedule which would have afforded time to correct the problem.

The mishap pilot knowingly and intentionally reset a Flight Control System Malfunction and continued to engage the opposing fighter. This was in direct violation of AFI 11-2F-16, Volume 3, paragraph 7.1.6: “For actual/perceived flight control malfunctions, pilots will terminate maneuvering and take appropriate action.” This was without cause or need given the engagement could have been terminated at any point for any reason without significant consequence.

While attempting over the top maneuvers on three separate occasions, the mishap pilot entered the low speed warning tone for a duration of 8-12 seconds without a TERMINATE/KIO and continued aggressive maneuvering in multiple axes of flight. This was in direct violation of AFI 11-2F-16, Volume 3, paragraph 3.9.5: “The minimum airspeed for all maneuvering is based upon activation of the low speed warning tone. When the low speed warning tone sounds, the pilot will take action to correct the low speed condition.” Intent was demonstrated by the mishap pilot during the mishap sortie by the number of times entering the low speed warning tone, the excessive duration of continuous activation of the warning tone with little urgency to recover, and progressively borderline setup parameters. According to mishap pilot testimony, these setup parameters are what he intentionally uses on a routine basis. It is implausible that a pilot would not encounter or expect to encounter the low speed warning tone in a two-tank configuration using these parameters; particularly, if a pilot employs more aggressive setup parameters for a maneuver immediately following one in which the tone was encountered using less aggressive parameters. These actions indicated the mishap pilot’s intent to repeatedly place the mishap aircraft in a low speed state with little urgency to recover or TERMINATE/KIO. This was done without cause or need given the engagement could have been terminated at any point for any reason without significant consequence.

The above violations indicate a lack of discipline by the mishap pilot…

The mishap pilot recalled appropriate and adequate application of the lap belt prior to takeoff. Specifically, he stated that it is his routine to “…keep the seat kit loose, so I can turn and look over my shoulder in the jet but I tighten the lap belt up as tight as I can get it”. Nonetheless, during the inverted departure the mishap pilot recalled falling away from the seat at least “1-2 inches” resulting in axial/inferior transfer of body mass to the canopy. This transfer left the mishap pilot with his helmet pinned against the canopy causing forward flexion of his neck, pulled his feet off the rudders, caused difficulty finding and deflecting the Manual Pitch Override switch in a timely manner, and caused difficulty maintaining positive control of the stick.

The mishap pilot specifically recalls that the abutment of his helmet to the glass of the canopy restricted his field of vision and limited his ability to effectively visualize terrain. He recalled being disoriented in this position, but not incapacitated. Even so, the mishap pilot stated that he never perceived the yaw rate. At this point, he was focused solely on the nose of the mishap aircraft in an effort to track vertical movement of the nose and cycle appropriate pitch rock maneuvers. He did not perceive horizontal movement of terrain.

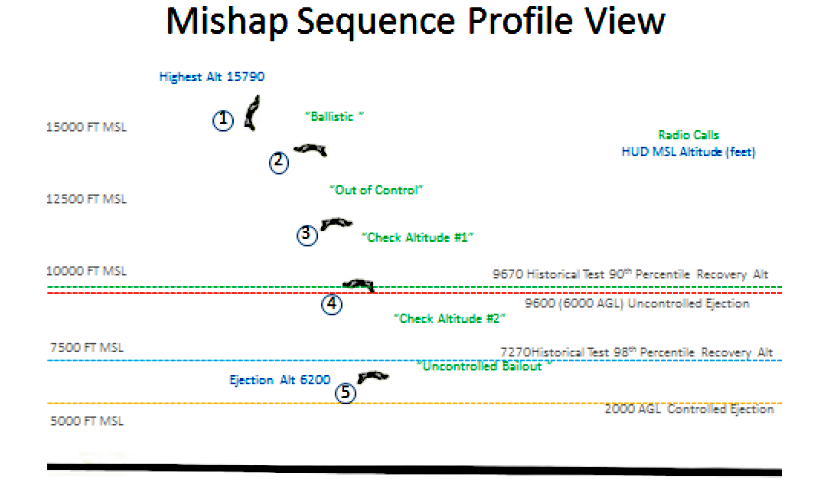

The inadequate restraint also hindered his ability to implement the Manual Pitch Override in a timely manner. The mishap pilot stated in his testimony that “…I kind of had to feel for it and I was using my right hand to hold onto the towel rack and kind of trying to push myself into the seat and brace myself a little bit with the right hand”. This assertion is further supported by Crash Survivable Flight Data Recorder data that showed a 31-second delay from aircraft departure to Manual Pitch Override switch deflection. Given his altitude at departure (15,770 ft. according to HUD tape) and the typical altitude required for recovery according to Lockheed Martin Flight Engineers, any delay in time would have been invaluable for mishap aircraft recovery prior to ejection altitude.

Finally, the mishap pilot’s displaced position within the cockpit affected his ability to make appropriate stick inputs. Mishap pilot stated difficulty maintaining positive control of the stick since he required use of his stick hand/arm to improve his position within the cockpit using the right body positioning handle or “towel rack”. Lockheed Martin mishap analysis of the Crash Survivable Flight Data Recorder data revealed stick inputs of a duration and magnitude inadequate to provide an effective pitch rock maneuver, particularly in the forward/push cycle. Specifically, the data showed that several forward/push cycles did not move beyond neutral…Since the Flight Control System automatically applies trailing-edge-up commands (or aft stick pull), it is critical for the pilot to apply full forward (push) stick force to facilitate successful recovery. A positional displacement towards the canopy and a resultant maximum extension of the mishap pilot’s right arm could have precluded his ability to push the stick beyond neutral to an effective magnitude. Therefore, this positional displacement contributed to the procedural anomaly of ineffective pitch rocking, precluding effective recovery.

The aforementioned factors resulting from inadequate restraint, in combination or alone, contributed to a significant delay in effective mishap aircraft recovery from a negative angle of attackl departure prior to ejection altitude…

Error due to Misperception is a factor when an individual acts or fails to act based on an illusion, misperception or disorientation state, and this act or failure to act creates an unsafe situation.

The mishap pilot stated he did not perceive yaw at any time during the departure. Following the onset of the negative angle of attack (inverted) departure, the mishap pilot recalled his field of vision being restricted due to a positional displacement into the canopy where his helmet contacted the canopy. While the mishap pilot denied incapacitation, he did recall some degree of disorientation during the deep stall. The mishap pilot recalled focusing his attention on the pitot tube on the nose of the mishap aircraft as he attempted to cycle the pitch rocking maneuver in phase with vertical oscillation. He did not recall the terrain or horizon moving in the horizontal plane. The mishap pilot never assessed the turn and slip indicator for direction and magnitude of yaw. Secondary to fixed attention on the vertical oscillation on the nose and limited field of vision due to his displaced position within the cockpit, the mishap pilot was unable to employ visual indicators of yaw. Particularly in a daylight scenario, visual cues serve as the most reliable indicators for perceptual orientation. Consequently, the mishap pilot was forced to rely solely on vestibular cues that erroneously suggested a state of neutral yaw. Data reproduced by the Crash Survivable Flight Data Recorder revealed a consistent yaw rate between 10 to 30 degrees per second, which was evident on the HUD tape as horizontal terrain movement and rate of change of the heading angle.

Appropriate Critical Action Procedures for recovery from an inverted deep stall in accordance with Air Force Instruction 11-2F-16, Volume 3, as compared to the mishap pilot’s actions were previously reviewed in detail. While the mishap pilot did eventually deflect the Manual Pitch Override switch and made an attempt at the pitch rock maneuver, Crash Survivable Flight Data Recorder data revealed no rudder inputs were made to neutralize yaw. Given the mishap pilot did not perceive yaw for the reasons discussed above, he made no attempt to input rudder. Technical Order 1F-16C-1 states attempts at pitch rocking before the yaw rotation stops or is minimized reduces the effectiveness of pitch rocking and delays successful aerodynamic recovery. According to the Lockheed Martin and Edwards Air Force Base flight engineer departure analysis for similar F-16 configurations, the mishap aircraft should have recovered within two pitch rocking cycles assuming yaw rate control and proper pitch inputs. In this instance, several cycles of the pitch rocking maneuver alone proved ineffective in recovering the mishap aircraft prior to ejection altitude.

The mishap pilot’s erroneous and unrecognized perception of neutral yaw coupled with channelized attention on the nose to the exclusion of reliable indicators of yaw rate led to the subsequent procedural failure to control yaw with rudder input…

I find by clear and convincing evidence the cause of the mishap was the mishap pilot’s failure to properly recover the mishap aircraft from a high pitch, low airspeed state resulting in an inverted deep stall. The mishap pilot then failed to properly input Out-of-Control Recovery Critical Action Procedures, resulting in an inability to recover the mishap aircraft before ejection. I also find by clear and convincing evidence three human factors caused the mishap: Complacency, Pressing, and Procedural Error.

I find by a preponderance of the evidence six other human factors substantially contributed to the mishap: Violation-Lack of Discipline, Seating and Restraints, Illusion-Vestibular, Spatial Disorientation (Type 1) Unrecognized, Channelized Attention, and Error Due to Misperception.

All this teaches us two things, and suggests a third:

— flying a modern military jet fighter is complicated.

— what happened 84 nautical miles east of Fresno, Calif., last Dec. 27 was no accident.

— how come there aren’t rigorous investigations of snafus like this for political leaders?