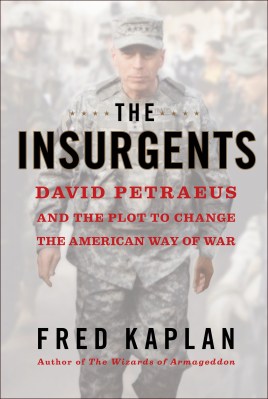

General David Petraeus in Iraq, 2007.

Fred Kaplan’s new book, The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War, dissects the past decade of American-waged battle to see how it has worked out. It assays the U.S. military‘s successes and failures, along with the squabbling over whether or not counter-insurgency, as championed by Petraeus, is the way to go.

Kaplan has the reportorial chops for the job. Now the military-affairs columnist at Slate, the online magazine, he authored The Wizard of Armageddon, about the Pentagon‘s nuclear-war priesthood, 30 years ago. Battleland conducted this email chat with Kaplan over the New Year’s weekend:

What is the bottom line in The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War?

It’s the story of a small group of intellectual officers, most of them from West Point’s Social Science Department, who conspired (they called themselves a “cabal” or a “mafia”) to revolutionize the Army from within. Like most revolutions, the ideas hardened into dogma, and so the story devolves into tragedy–or, to put it another way, Afghanistan.

How big of a change was it, really? How complete is this change?

The idea was to transform the U.S. military, especially the Army, from a Cold War garrison establishment that saw war as strictly large-battlefield, tank-on-tank conflict, to an expeditionary force engaged in “irregular warfare” or “counterinsurgency campaigns.”

The Army did go through a cultural change; it is more a “learning” organization than before; its concept of war, and how to think about it and prepare for it, is more flexible. And it succeeded, tactically anyway, in Iraq.

But when the officers tried to apply the principles to Afghanistan, it was a disaster, and everyone knew it. President Obama, who had accepted the ideas as a short-term experiment, backed away explicitly. So the ideas are still enshrined in Army doctrine, but it’s not at all clear how enduring they will be.

Isn’t the nation tired of manpower-intensive counter-insurgency campaigns?

Absolutely. Nobody, not even David Petraeus, thinks we’ll get involved in another Iraq or Afghanistan anytime soon.

One of his proteges, Colonel John Nagl, even said that counterinsurgency works best in a place like post-World War II Malaya — “on a peninsula against a visibly obvious ethnic minority, before CNN is invented.”

By the way, a lot of these officers thought it was stupid to invade Iraq in the first place–partly because it diverted resources and attention from Afghanistan, which fell apart very quickly after Bush moved on to the next war.

Still, they also think that insurgency wars tend to happen once every generation – at intervals just long enough for the leaders in power to have forgotten the lessons of the previous war – so officers should have some idea of how to fight them.

What’s the downside, if any, of waging war with drones and hundreds of special operations troops, instead of tens of thousands of soldiers and civil affairs specialists?

War becomes too easy; it’s too tempting to fire a missile from a drone when you can’t think of anything better to do. As I write in the book, this kind of technology is “an alluring anesthetic that numbs the senses to the pain of warfare: the grit, grime and mayhem of its consequences on the ground.”

Did you find in your reporting and research that the “how” of waging war by the U.S. military is like the tides, cycling from one favored method to another, and then back again, ad infinitum?

Yes. Petraeus and his entourage weren’t pushing anything new.

The strategy had roots in the 19th century. The U.S. tried it briefly in Vietnam and El Salvador. It tends to rise to the surface when the more traditional tactics–heavy firepower, indiscriminate bombing, bashing down doors, that sort of thing–don’t work.

But then the “better, smarter war” strategy turns out to be inherently protracted, and bloodier than the rhetoric makes it seem. So we turn against it too.

The truth is, war is hell, however you define it, and unless the national-security interests are very high (and they were never so high in Iraq or Afghanistan, at least not after bin Laden was killed and al Qaeda was decimated), nobody wants to burn for a long time in hell.

Why should the average American read The Insurgents?

First, it’s a good story. I’m interested in stories about people, ideas, and power–and how they converge in politics and policy. What heightens the importance of this story is that the stakes are so high. The politics and policy are about war.

How we fight wars means life or death for thousands of Americans–means success or failure for America’s standing in the world. Even if you think you’re not interested in this story, it’s interested in you; you can’t escape it.

Rattle off three of the juiciest nuggets your book contains.

I don’t know if it’s a nugget, but one persistently juicy motif, or theme, is how much of Petraeus’ successes stemmed from his assertiveness, even brazenness.

As commander in Iraq, he needed to pay a lot of Sunni militants to flip to the U.S. side, so he just did it, using money from his discretionary fund, without telling anyone in Washington.

His predecessor had obeyed orders from Iraqi’s prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki, not to send troops after Shiite militants in the Baghdad neighborhood of Sadr City; Petraeus just did it, without telling Maliki ahead of time. There are lots of examples of this sort of thing.

A second nugget: much of the Army brass hated Petraeus; they didn’t like officers who were too bookish or stood out too much, and Petraeus was a case-study in both.

When he came back to Iraq for his second tour, the commander, General Ricardo Sanchez, called his staff in to meet him. Newsweek had just put Petraeus on the cover with the headline, “Can This Man Save Iraq?”

During the Q-A, Petraeus answered all the questions, though Sanchez was his superior. At one point, a staffer directed a question specifically to Sanchez. Sanchez dryly replied, “I don’t know, why don’t we let the Messiah take that one.”

A third example: I don’t know if it’s juicy, but it’s one of my favorite scenes in the book. It’s about Colonel Conrad Crane, the co-author of Petraeus’ counterinsurgency field manual, a modest, almost shy soldier-scholar.

Every time he goes back to West Point, he stops off at the academy’s cemetery. Six thousand former cadets are buried there, dating to the Revolution.

But Crane heads to the back rows, where the fallen from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars are laid to rest. At least three of them were students of Crane’s, a fact that pains him; he’s aware that some of them died while following the instructions he’d helped write.

He hopes, he has to believe, that the manual, and the new strategy it brought forth, saved more soldiers’ lives than it cost, but he also knows he will never be sure. As I said, the stakes in this story are high.

How distressed were you to see Dave Petraeus resign in scandal, given that his name and picture are on the cover of The Insurgents?

Like most people, I was surprised, mainly because he’d spoken with such scorn about officers who’d been drummed out of the service for infidelity. (Adultery is a crime under the military’s code of justice.)

But he’d gotten away with so much, even if his previous transgressions had been at the service of military goals in wartime, he apparently thought he’d get away with this too.

But I don’t think it diminishes the story I’m telling: this is the story of war and peace in our time; the Army went through a revolution, and he was its ringleader. That will be remembered for much longer than the affair.