Soldiers of the U.S. Army's 82nd Airborne in Afghanistan.

I graduated high school and entered college, and ROTC, in 1973 – the year we transitioned to the all-volunteer force (AVF).

Georgetown University was not exactly a hotbed of student activism, but as I recall ROTC was unpopular enough that we didn’t wear our ROTC uniforms to and from class – they were kept in Old North where our classes met.

I was, therefore, a bit taken aback when one of my professors, known to me to be very liberal, stopped me in the hall one day and asked if it were true that I was in ROTC. I cautiously confessed the truth, and was surprised and (somewhat) relieved at his response:

That’s good, because the military is too important and too dangerous to be left to those who want to be in it.

His was a minority view then, and, if anything, most Americans since that time have shown that they are not only willing, but eager, to leave the military to whoever would like it, so long as they are not called upon to serve.

When possible renewal of the draft has been mentioned in recent years, by people like Charles Rangel or more recently Tom Ricks, the silence has been deafening.

Poll after poll has shown that Americans do not want conscription. Even the military, once a strong opponent of ending the draft, now staunchly opposes the idea of returning to conscription.

The military and economic pros and cons of having a draft have been discussed many times, and a frank re-visitation of those issues may now be timely as we gain some perspective on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It might be profitable as well to include in that discussion some consideration of the psychology of having a draft, or more to the point, not having a draft.

Can psychology help us understand how current attitudes of both civilians and military members may be conditioned by this 800-pound gorilla we have become so good at ignoring?

I teach introductory psychology and I take, as many of us do, an explicitly functional, even evolutionary, approach. I want my students to see how adaptive our behavior is, and to this end I try to connect for them things like generalization and discrimination in conditioning and learning, top-down processing in perception, memory as a constructive process, schemas and heuristics in cognition, and so on as adaptations that have the effect of making us more efficient processors of information. These are all ways that we use our past experience to inform current processing: we may not always come up with the right answer, but mostly we do, and we do so more efficiently.

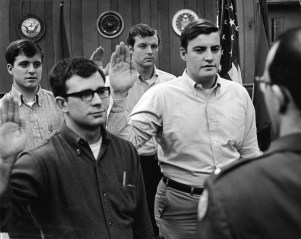

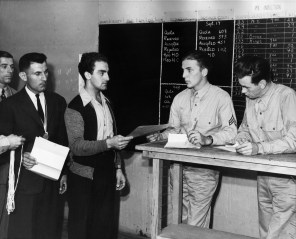

1941: Readying for World War II

I also like to talk about what I think of as our “inner spinner” – a set of adaptations that operate to promote consistency between the world as we believe and want it to be and the world as it is.

One example of such an adaptation is the self-serving bias in attribution. This bias is easily demonstrated by calling your broker when the market is doing well and asking him/her to review your portfolio. You’ll be regaled with example after example of the wise choices he/she has made in selecting just the right places to invest your hard-earned money.

Now try calling when the market is in the tank: what you’ll hear is a sad tale of vast market forces beyond anyone’s control, often leavened with scathing criticism of business and (more often) government leaders, but very little if anything about the really dumb choices he/she may have made.

Another example of our inner spinner at work is our tendency to reduce cognitive dissonance. The classic study of Festinger and Carlsmith (1959) illustrates this tendency. Experimental subjects were asked to perform a boring task (turning knobs on pegs) and were paid either $1 or $20 for their efforts. They were then asked to tell others that the task was actually fun and interesting.

Having thus misled others, they were then asked to rate the task themselves. Many of us intuitively expect that the subjects paid $20 will rate the task more positively, but in fact it is the subjects who were paid $1 who do so. The explanation is that for the subjects who were paid $20, there is no dissonance between thought and deed to reduce: I did something boring and lied about it for 20 bucks – not pretty, but rational.

The subjects paid $1, however, find themselves in a quandary: they spent time doing something boring and distasteful for a pittance. Why would I do this? I can’t change the pittance, but if the task really wasn’t that boring, my behavior is more rational. So, my attitude toward the task shifts in a positive direction, and the world makes more sense.

With this background in mind, we can return to the question of the draft.

One phenomenon that has attracted the attention of more and more of us lately is the nature of civilian attitudes toward the military. Poll results show that the military is at the top of most Americans’ list of admired and trusted institutions (Congress is at the bottom). This admiration and trust is also extended to individual military members.

Members of the military are the recipients of lavish and unconditional praise and gratitude, yellow ribbons are everywhere, special discounts and benefits for military members are ubiquitous. Those of us who remember 1973 know that sadly, things were very different then: the military was held in quite low esteem by civilian society.

Why the change since then?

A successful AVF is necessary if we are to continue without a draft. There are other, more noble reasons for America’s current adulation of the military, but maintaining a positive image of the military does prevent dissonance between our desire to avoid a draft and the potential need for conscription were the AVF to prove inadequate.

Given the reality that Americans do not want a draft, full stop, our inner spinner is motivated to adjust our perceptions of the AVF to ensure cognitive tranquility. When we hear that the military is not performing as well as it might, the first response is often to send more money as needed. The military has been largely excused from discussions of budget reductions, and even when the military is included in these discussions, personnel pay and benefits are often exempted.

We apparently want the AVF to be successful and have what it needs, so long as what it needs is not us.

We also seem to manage our attributions in ways that are consistent with our beliefs. Soldiers who misbehave, for example, are usually accorded the benefit of the doubt: the first response in the media is usually to mention combat stress, repeated deployment, and PTSD as possible contributors to misconduct.

These external attributions allow us to maintain a positive view of our own soldiers, but such situational variables are rarely mentioned when discussing our enemies. Ideological and religious motivations normally come up pretty quickly in discussions of the Taliban, or other insurgents.

This tendency extends as well to assessments of the success of the wars themselves. A majority of Americans feels that the war in Iraq was ill-advised and that we should leave Afghanistan sooner rather than later. Many feel that the wars accomplished little of lasting benefit.

But one rarely hears criticism of the commanders and generals, and frequently hears criticism of civilian political leaders in this context. The idea that a competent military may be handicapped by civilian political restrictions or interference is another legacy of the Vietnam era. But doesn’t the military play a powerful and central role in defining for civilian leaders what is, or isn’t, advisable from a military standpoint?

Quite aside from the policy consequences of America’s new attitude toward the military, there may also be psychological consequences for military members themselves that we should consider.

One of these is the contempt in which many military members hold civilian society. Many in the military (and many civilians) see civilian society as corrupt and degenerate, and generally inferior to military culture. Leaving aside the political and demographic contributors to these attitudes, we should not be surprised if military members harbor them.

Civilians ostentatiously support the military with very little real knowledge of what it is they are supporting. Soldiers know the sometimes elevating and inspiring and the sometimes ugly truths about military life and war, and know that not all soldiers are equally deserving (or deserving at all) of the kind of appreciation heaped upon all in the military.

Praise that is seen as indiscriminate or false or unjustified is insulting, and may reveal something unpleasant about the person delivering the praise: that its purpose is fundamentally self-serving. Unqualified and effusive praise can make soldiers feel fraudulent because they (unlike many civilians) actually know what they did and didn’t do to deserve it.

Many thousands of military members have made sacrifices over the last decade that every American citizen should understand, appreciate and remember. The dedication, heroism, and courage of many in our military are truly awe-inspiring. It is the sense of doing something powerfully important that gives meaning to these sacrifices for those who serve.

One must ask, though, if one economic consequence of having an AVF as opposed to a draft-based military potentially compromises the capacity of soldiers to make meaning of their experiences. As recruiting became more difficult with increasing combat intensity in Iraq, recruitment standards were lowered and ever more lavish monetary incentives and other benefits were (and continue to be) offered to soldiers.

In a way, a member of a conscripted military, in which soldiers generally receive lower pay and benefits than in volunteer militaries, might be compared to the $1 group in the Festinger and Carlsmith study, while members of a volunteer force, especially one very well compensated, might correspond more to the $20 group. When financial benefits are less obvious and prominent, perhaps it is easier for service members to see the more significant underlying motivations to serve, and to make meaning of that service.

None of the foregoing is intended to serve as support for an argument either for or against the draft, or for or against some form of universal service. My intention is only to note what may be, at least in part, unintended consequences of our transition to an all-volunteer force that are understandable in psychological terms.

Most (though by no means all) of our allies also have all-volunteer forces, but the kind of civilian adulation of the military we see in America is not seen elsewhere. Why not? There may well be historical or political factors which contribute to this difference – the legacy of Vietnam might be a good starting point in looking for this context.

If you’ve read this far, though, you may agree with me that there is not likely to be much appetite for delving too deeply into this. We’re rather happy with the way things are, and are quite likely to continue to see a great deal of evidence to confirm our belief that the AVF is working very well.

Dr. George Mastroianni is a professor of psychology at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo., and writes the Headspace blog – “a social science look at the military” — on Psychology Today’s website. The views expressed are his own and may not reflect those of the Air Force or Department of Defense.