Rescue boats move in on the battleships U.S.S. West Virginia and U.S.S. Tennessee which sit low in the water and burn after the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on Dec., 7 1941.

The “infamy” of December 7, 1941, is deeper than most Americans have ever imagined. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was almost certainly the result of a Soviet plot—“Operation Snow”—carried out by Harry Dexter White, a figure of enormous influence in the Roosevelt administration and a known Soviet spy.

Americans remember Pearl Harbor as the work of a Japanese military machine hell-bent on a war of conquest. The truth is more complicated.

The imperial regime had faced severe political shocks throughout the 1930s. Two attempts on the life of Emperor Hirohito—one by a Japanese communist whose father was a member of parliament, another by a Korean patriot—were followed by the assassinations of prominent bankers and cabinet members.

(PHOTOS: After Pearl Harbor, Life in the Pacific and on the Home Front)

After Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai was murdered in 1932 for his failure to cope with the Great Depression and to curb foreign influence, 110,000 Japanese petitioned for clemency for his assassins. Four years later, in a sensational coup attempt, young military officers cornered Prime Minister Kesisuke Okada in his own bathroom, slew his look-alike brother-in-law, and nearly wiped out the cabinet.

The emperor feared assassination by his own officers if he knuckled under to American or Russian threats to Japan’s economic and military interests, especially access to American oil.

The Russians, meanwhile, knew that they could not simultaneously repel an expected German invasion from the west and respond to the Japanese threat from the east. A series of skirmishes with the Japanese at Nomonhan in 1939 had revealed serious weaknesses in the Soviet military.

The NKVD, predecessor of the KGB, knew that a war with the United States would divert Japan from its ambitions in Mongolia and Siberia—threats that tied up 25% of the Red Army—and allow Russia to deploy its full military power against the Germans. Fortunately for Stalin, his intelligence service had an “agent of influence” in Washington perfectly situated to provoke a U.S.-Japanese war—Harry Dexter White, a high-ranking Treasury official.

Born to a working-class immigrant family in Boston, White had served as a non-combat officer in World War I. He earned a doctorate in economics from Harvard but was unable to land an academic post in the Ivy League, in part because of anti-Semitism, and in part because of his own abrasive attitude toward subordinates.

By the time he went to work in Franklin Roosevelt’s Treasury Department, he had developed communist sympathies, and by 1936, with the assistance of Whittaker Chambers, he was leaking information about Japanese and Chinese politics and economics to the NKVD.

Fearing exposure, White temporarily gave up his subversive activities. But in May 1941, as the non-aggression pact between Hitler and Stalin began to unravel, NKVD agent Vitalii Pavlov managed to reactivate White with an urgent mission—to provoke a war between the United States and Japan so that Russia would not have to fight on two fronts.

From his perch in the Treasury Department, White had become closely acquainted with the key figures in FDR’s administration. He knew, for instance, that Stanley Hornbeck, the State Department’s expert on Asia, hated the Japanese and believed that Asians were naturally timid and easily bluffed. And White wielded enormous influence with his boss, Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthal Jr., whose personal friendship with the president made him the most powerful member of the cabinet.

Skillfully manipulating Morgenthau and Hornbeck, White was able to turn U.S. policy toward Japan in an increasingly belligerent direction. When FDR almost agreed to relax a U.S. oil embargo in return for Japan’s gradual evacuation of China, White drafted a hysterical letter for Morgenthau’s signature:

To sell China to her enemies for the thirty blood-stained coins of gold, will not only weaken our national policy in Europe as well as the Far East, but will dim the bright luster of America’s world leadership in the great democratic fight against Fascism.

Instead of compromising, the United States demanded that Japan withdraw from China immediately, neutralize Manchuria, and sell three-quarters of its military and naval production to the U.S.

Perceiving the demand as an insult and a threat, the skittish Japanese government concluded that war was inevitable. They moved ahead with a contingency plan for an attack on the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor and the Philippines, and Stalin, thanks to Harry Dexter White, were spared a war on his eastern flank.

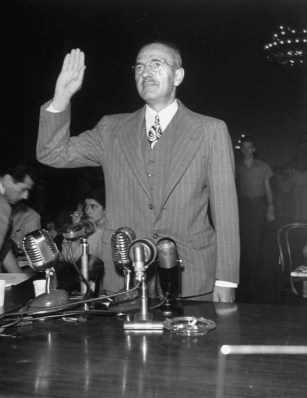

White continued to shape U.S. policy to Soviet advantage into the postwar era until the revelations of the communist defectors Whittaker Chambers and Elizabeth Bentley precipitated his spectacular fall.

He died in 1948, quite possibly a suicide, three days after a disastrous appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He was identified as a traitor by the FBI in 1950, but the full story of his role in provoking Pearl Harbor was unknown until Vitalii Pavlov, his Soviet handler and ultimately a lieutenant general in the KGB, published his memoirs in 1996. Pavlov credited White with saving the Soviet Union.

John Koster is the author of the recently-published Operation Snow: How a Soviet Mole in FDR’s White House Triggered Pearl Harbor. An Army veteran, he lives in New Jersey.