President Obama delivers remarks in Chicago early Wednesday after being elected to a second term.

President Obama – despite campaign claims made by Mitt Romney and other Republicans – hasn’t slashed Pentagon spending during his first term. Nor did he shy away from making tough decisions – killing Osama bin Laden chief among them – in his role as commander-in-chief.

To the degree national-security issued played any role in Obama’s re-election, those facts helped push him across the finish line in first place. For his second term, he’s likely to embrace the national-security blueprint sketched out by his then-defense secretary Robert Gates last year.

And it’s a small thing, overall, but Obama and his staff touched the right military notes throughout the campaign, and in his victory speech early Wednesday from Chicago. Military folks crave not praise so much as acknowledgement, which seemed to be a recurring blind spot for GOP challenger Mitt Romney.

Obama poured it on Wednesday morning, lauding “a military spouse who’s working the [Obama campaign’s] phones late at night to make sure that no one who fights for this country ever has to fight for a job or a roof over their head when they come home” and “a nation that is defended by the strongest military on earth and the best troops this world has ever known.” Troops tend to ignore the political implications of such comments, but they don’t ignore being ignored.

Voter weariness with the wars – the rocket fuel for the Pentagon’s spending engine over the past decade – and satisfaction at bin Laden’s demise, came together to improve the Democratic President’s bona fides on national security. Even the stain caused by the militant attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, two months ago – which killed the U.S. ambassador and three other American officials – didn’t seem to hurt much.

A quick survey of the globe – and U.S. budget woes – suggest Obama will increasingly rely on special-operations forces and drones to hunt down and kill al Qaeda and other terrorists. They’re doing it already in Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen. They can do it in Afghanistan, as well, after U.S. combat forces leave by the end of 2014, after 13 years of war — and halfway though Obama’s final term.

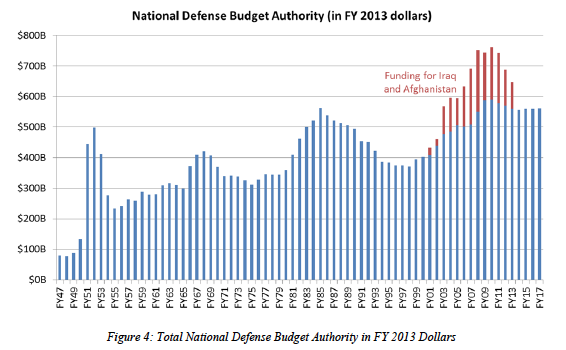

But the fiscal bottom line is clear: growth in U.S. military spending is likely to dip in Obama’s second term, especially if he and Congress can’t agree on a $1.2 trillion deficit-reduction package by Jan. 2. If they fail to do that, the dreaded legislative mandate of sequestration will occur. That would chop about another $500 billion from the Pentagon’s proposed spending plans for the coming decade, on top of $487 billion in cuts already made.

All told, that would cut about $1 trillion from the Pentagon’s original $7 trillion spending plan – about 15% overall – and push U.S. military spending down to 2007’s level. Yet the U.S. military’s annual budget would still top the Cold War average.

“Given the way the Congress has acted, it’s kind of hard to assume that they’re going to actually do anything constructive,” Frank Kendall, the Pentagon’s top weapons buyer, said Monday. “But I am an optimist, and I’m hopeful that there’d be some breathing space that we have not had in these last few years, after the election.”

Inheriting two wars that have cost $2 trillion and 6,000 American lives, Obama plainly got some bump at the polls for winding them down – even if both Iraq and Afghanistan remain violent.

Beyond the political payoffs wrought by concluding the conflicts – a welcome salve for a U.S. public grown tired of seemingly inconclusive wars – Obama has a hole card in his pocket: the advice offered up by Gates, his first (and President George W. Bush’s last) defense secretary.

In his final months as defense chief, the well-regarded Gates went to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and looked into the eyes of the Army’s future officers and told them that huge land wars are probably not in their future:

In the competition for tight defense dollars within and between the services, the Army also must confront the reality that the most plausible, high-end scenarios for the U.S. military are primarily naval and air engagements – whether in Asia, the Persian Gulf, or elsewhere. The strategic rationale for swift-moving expeditionary forces, be they Army or Marines, airborne infantry or special operations, is self-evident given the likelihood of counterterrorism, rapid reaction, disaster response, or stability or security force assistance missions. But in my opinion, any future defense secretary who advises the president to again send a big American land army into Asia or into the Middle East or Africa should “have his head examined,” as General MacArthur so delicately put it.

That, in a nutshell, is Obama’s template for his second-term Pentagon, complete with a Republican defense secretary’s imprimatur.