A U.S. Army Captain with the 82nd Airborne Division, left, talks strategy with some of his Afghan National Army comrades in June in Ghanzi province.

For reasons that were quite clear well before the Afghan “surge” began (see here and here), America’s Afghan adventure is now ending without achieving its goals, despite Defense Secretary Leon Panetta’s claim Wednesday in Brussels that “significant progress” has been made in the war.

To the contrary, the Taliban have survived the U.S. troop surge with its fangs and shadow governments intact; they have no incentive to negotiate, and they are poised to launch a spring offensive in 2013.

The prospects for a civil life in Afghanistan are likely to become even more remote than they were before we intervened.

Indeed, some experts think the ground work has been laid for a disastrous civil war, perhaps even worse than that which occurred after the Soviets left Afghanistan in 1989 with their tail between their legs. Only time will tell how bad things will be, but a recent report by Gilles Dorronsoro for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace explains quite persuasively why it is now virtually certain that events in Afghanistan will be ugly and murderous.

One would expect a healthy democratic government, one based on the principle of accountability, would be intent on learning from its errors and inclined to seek an understanding of how it got itself into such a mess.

For example, will there be a soul-searching “lessons-learned” exercise by a U.S. military that repeated most of the strategic and tactical blunders it made in Vietnam?

To wit: it dumbed down its military strategy into one of mindless attrition driven by body counts and assassinations. It substituted high-cost contractor-intensive technologies for low-cost tactical smarts in a guerrilla war. It over-relied on air power and killing from a safe distance. It allowed its reactive obsessions with force protection to displace the tactical initiative of its small unit commanders and to isolate our troops from the local population we were claiming to protect.

Taken together, as in Vietnam, our strategic predilection for technology-intensive attrition warfare, conducted from a safe distance, converted a counter-guerrilla war that was initially aimed at winning the hearts and minds of an indigenous people into an unfocused killing campaign that alienated the very people the strategy was trying to attract — in this case the Pashtuns in Pakistan as well as Afghanistan.

Perhaps most decisively, as in Vietnam, the American military relied on a fatally flawed grand strategy centered on a plan to quickly create a huge, materiel-intensive, indigenous army out of whole cloth, trained and equipped in the U.S. military’s image. And like in Vietnam, the result is a huge, ineffective, corrupt institution that could not stand alone, and thereby has guaranteed we cannot end our Afghanistan adventure on terms that do not sow the seeds for future conflict.

Don’t expect to hear any questions about these issues in the presidential debates, including Thursday’s vice-presidential showdown. And don’t expect to see any serious introspection by a military-industrial-congressional complex (MICC) intent on perpetuating its lucrative business-as-usual.

Will there be an accounting at home for our complicity in causing this human disaster?

U.S. complicity in the Afghan nightmare reaches back more than 30 years to the Carter Administration’s successful efforts in the summer of 1979 to sucker the Soviets into invading Afghanistan.

The idea was simple, according to President Carter’s national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski: fan the fires of Islamic extremism (with the help of Saudi Arabia and Pakistan) in Afghanistan to increase the Soviet leadership’s paranoid fears about a spillover of religious unrest into the Soviet Central Asian republics.

The Soviet leadership’s obsessive fear would increase the likelihood of a defensively-motivated preemptive Soviet invasion, and in so doing, would enmesh the Soviet Union in a Vietnam-like quagmire. Brzezinski bragged about this gambit in an interview with the French magazine Le Nouvel Observateur in 1998. When asked if he regretted having supported Islamic fundamentalists or giving arms and advice to future terrorists, Brzezinski’s responded: “What is most important to the history of the world? The Taliban or the collapse of the Soviet empire? Some stirred-up Moslems or the liberation of Central Europe and the end of the Cold War?”

Unfortunately Brzezinski’s stirred up Muslims have become obsessively important to Democratic and Republican interventionists. But don’t count on any soul-searching questions about how this happened in the presidential debates.

There is another subject that seems to be verboten in the U.S. media but ought to be addressed in the presidential debates, because it is certain to haunt whoever is President over the next few years: Just how in hell are we going to extract our forces and the bulk of their equipment from Afghanistan? And how much is it going to cost?

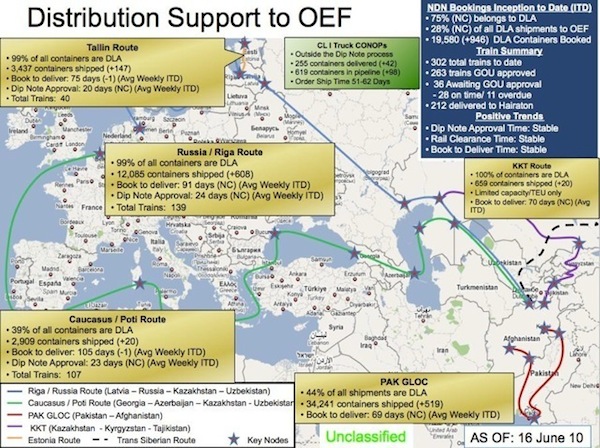

The vast bulk of our heavy equipment has gone into Afghanistan via land routes thru Pakistan. Here is a Pentagon chart illustrating the land lines of communications (LOCs) and the capacities and delivery times of each option, as of two years ago.

DLA

Unlike the Soviets, the United States does not have a short land route out of a quagmire created by Brzezinki’s stirred up Muslims. Pakistan is by far the best route out, but we have alienated the Pakistani population, particularly the Pashtuns, with our drone attacks. The northern routes are far longer, horrendously complex, have lower thru-put capacities, rely on far more dangerous mountain roads, and have far more transshipment points.

Protecting these lines of communications (LOCs) in what the Brits have called the looming Afghan Dunkirk is not a new or unforeseeable military problem. Alexander the Great was forced to build a string of fortresses in Afghanistan along many of these same routes to protect his LOCs, because, as Plutarch said, fighting Afghan tribesmen was like fighting a hydra headed monster; a soon as Alexander cut off one head, three more grew back in its place. There is even one apocryphal legend that Alexander the Great had to bribe the Pashtuns to let part of his forces exit Afghanistan thru the Khyber Pass.

The answers to the questions surrounding our exit from the Afghan quagmire include a bill that should be calculated in the currency of lives lost or ruined, materiel worn out or left behind, and dollars, especially the increases in the budgets that will be demanded by the Pentagon to replenish its lost and worn out equipment.

Don’t expect to hear them.

One the other hand, one subject we might hear in the Presidential debates is an argument over who will be the bigger macho man as the United States pivots its national security strategy toward East Asia (i.e., China). This pivot has the great advantage of being a convenient cover for the Pentagon — really the MICC — to sweep Afghanistan’s lessons under the table and continue high-cost business as usual.

Who knows? With a little luck, maybe we can start a new Cold War with big budgets and no fighting, because we have just about reached the end game in our exploitation of “stirred-up Muslims” as a means to pump up the defense budget.