An F-35 Lightning II over Florida's Eglin Air Force Base.

On June 14 — Flag Day, of all days — the Government Accountability Office released a new oversight report on the F-35: Joint Strike Fighter: DOD Actions Needed to Further Enhance Restructuring and Address Affordability Risks. As usual, it contained some important information on growing costs and other problems. Also as usual, the press covered the new report, albeit a bit sparsely.

Fresh bad news on the F-35 has apparently become so routine that the fundamental problems in the program are plowed right over. One gets the impression, especially from GAO’s own title to its report, that we should expect the bad news, make some minor adjustments, and then move on. But a deeper dive into the report offers more profound, and disturbing, bottom line.

Notorious for burying its more important findings in the body of a report — I know; I worked there for nearly a decade — GAO understates its own results on acquisition cost growth in its one-page summary, which—sadly—is probably what most read to get what they think is the bottom line.

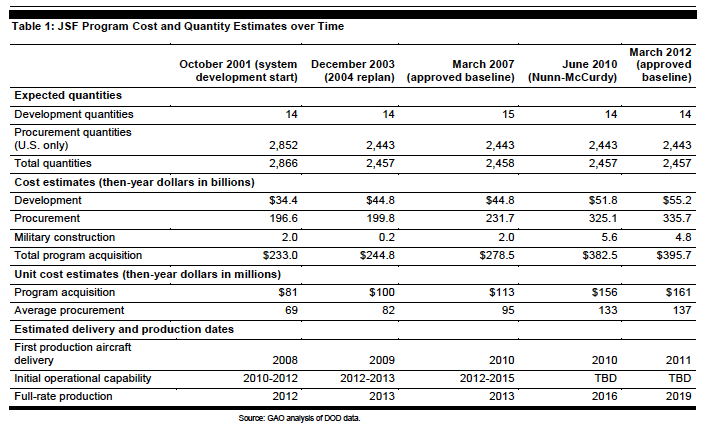

In that one-page summary, GAO states the F-35 program now projects “costs of $395.7 billion, an increase of $117.2 billion (42 percent) from the prior 2007 baseline.” The much more complete story is in this table from the report:

The summary uses the wrong baseline. As F-35 observers know and as the table shows, the cost documentation of the F-35 program started in 2001, not 2007. There has been a lot more cost growth than the “$117.2 billion (42 percent)” stated.

Set in 2001, the total acquisition cost of the F-35 was to be $233.0 billion. Compare that to the current estimate of $395.7 billion: cost growth has been $162.7 billion, or 70%: a lot more than what GAO stated in its summary.

However, the original $233 billion was supposed to buy 2,866 aircraft, not the 2,457 currently planned: making it $162 billion, or 70%, more for 409, or 14%, fewer aircraft. Adjusting for the shrinkage in the fleet, I calculate the cost growth for a fleet of 2,457 aircraft to be $190.8 billion, or 93%.

The cost of the program has almost doubled over the original baseline; it is not an increase of 42%.

Now, you know why DOD loves the rubber baseline. Reset the baseline, and you can pretend a catastrophe is half its actual size.

When assessing the other, even larger, “sustainability” cost implications of the F-35, GAO makes what I regard as a major methodological error.

On page 11, GAO cites DOD’s goal for the additional operating, logistics and support costs (“sustainment”) of the F-35. GAO focuses on the Air Force’s conventional take-off and landing (CTOL) variant and cites the new, March 2012 goal: $35,200 per flight hour, compared to $22,500 for the F-16. For years, DOD has cited the F-16 as the comparison aircraft for calculating costs to operate the F-35; now it is hoping the F-35 will be only 56% more than the cost to sustain the F-16.

GAO, quite properly, offers some skepticism that this goal can be met. It states that the CTOL version is not achieving its own criteria for meantime between failures, falling 30% short in 2011 (page 30); GAO reports that operational testers said “JSF is not on track to meet …operational suitability requirements” (page 17), and finally, GAO says the program is experiencing “excessive time for low observable repair and restoration, low reliability, and poor maintainability performance” (page 17). After all that, GAO politely calls the sustainability cost goal “a significant challenge” (page 31).

GAO is also correct to point out DOD management’s declaration that the current F-35 operating cost estimate, “$1.1 Trillion for all three variants based on a 30-year service life,” (page 10) is “unaffordable and simply unacceptable in the current fiscal environment” (page 11).

However, comparing the F-35 to the F-16 is a major error; associating those two aircraft is simply implausible. The two have very, very little in common. While they both are single engine aircraft that were planned to cost less than their contemporary higher cost complements (the F-15 and the F-22 respectively), the basic similarity stops there. The F-16 was conceived as a visual-range air to air fighter in the 1970s; it is a far, far more simple design, and it met its inherent affordability goal. The F-35A is a multi-role, multi-service design with stealth and many other highly complex (so-called “5th Generation”) attributes added in. It is a far, far more intricate aircraft and, as a result, failed to meet any affordability goal.

The F-35A has much more in common with its Lockheed stablemate, the F-22. While the F-22 may be more complex in some respects (twin-engine with divertible thrust; earlier generation stealth coatings); in other respects the F-35 is the more complex aircraft of the two (basic multi-role design woven into a STOVL-capable, multi-service airframe, even more complex communications, sensor and display systems, and much more software and complexity of system integration).

The F-35’s fundamentally complicated (“5th generation”) design makes its comparison to the F-16 inappropriate in any effort to understand F-35 operating costs. It should be compared to the F-22 where the similarities abound, for the most part. To better predict unknown F-35 costs, we should start with known F-22 operating costs.

The Air Force has been recording costs per flying hour for the F-22 since 2003. Six years after 2005 when the Air Force declared “initial operating capability” (IOC or the presumed ability to deploy and fight) for the F-22, the Air Force officially calculated an “ownership” cost per-flying-hour for the F-22 at $128,389 [best to download this with Google’s Chrome browser]. That amount, however, is an outlier: the F-22 was grounded for more than four months that year, thereby distorting upwards the per-flying-hour cost.

There were no F-22 groundings or other significant flight limitations in 2010; the data for that year reflect known sustainment costs, per hour, after five years of deployability, thereby reflecting any learning curve in F-22 maintenance and support. The Air Force’s “ownership” cost per flying hour for the F-22 in 2010 was $63,929: half the 2011 cost.

It is that amount that should serve as the starting point for considering plausible F-35 operating costs. Optimistically speaking, a downward adjustment can be made for the F-35: Lockheed is attempting to reduce the cost and maintenance hours needed for the F-35’s version of stealth coatings, which comprises a large portion of F-22 operating costs, and an allowance should also be made for the single engine design of the F-35.

However, it is currently unknowable whether the lesser stealth cost goal will be achieved (as noted above, GAO found the F-35 is encountering problems), and it is also unknowable if the single engine design compensates, or not, for the added operating costs for the more complex communications, sensors, displays and software integration. While highly optimistic, perhaps a 20% improvement over the F-22 can be analytically useful.

Assuming that 20% cost per-flying-hour improvement over the F-22, the F-35 would cost $51,143 per hour to fly. Rather than an F-35A operating cost that is 56% more than the non-analogous F-16; it is more plausible, and analytically conservative, to calculate an operating cost that is 80% less than the highly comparable F-22—even if the improvement has not yet been demonstrated. The question should not be whether the F-35 can achieve 156% of the operating cost of the F-16; it should be whether it can achieve 80% of the operating costs of the F-22.

Posing the question in that manner, however, presents a serious dilemma: if the currently projected estimate of operating costs for the complete fleet of all three F-35 variants of $1.1 trillion is “unaffordable and simply unacceptable,” what is the meaning of a plausible—even if optimistic—operating cost that is well above that unsustainable $1.1 trillion?

During the nine years I worked in GAO’s methodology division, specializing in national-security evaluations, we took very seriously the selection of reasonable criteria for the purposes of comparing DOD systems. When DOD’s criteria were biased, we selected more appropriate ones. In this recent report, GAO failed to take that step.

We also used to joke in the cafeteria about the tepid titles senior management would give the reports we wrote. This new GAO report, Joint Strike Fighter: DOD Actions Needed to Further Enhance Restructuring and Address Affordability Risks is very unfortunate example: it does not simply understate the message the data convey; it misstates what the data say. The cost growth inherent in the F-35 program is huge and still growing: far more than to “enhance restructuring” and “address affordability” is needed.

The F-35 should now be officially called “unaffordable and simply unacceptable.” All that is lacking is a management that will accept — and act — on that finding.