We’ve had a flurry of books written by troops recounting their battles in Afghanistan and Iraq. Now come the books detailing the battles fought once they got home.

We’ve had a flurry of books written by troops recounting their battles in Afghanistan and Iraq. Now come the books detailing the battles fought once they got home.

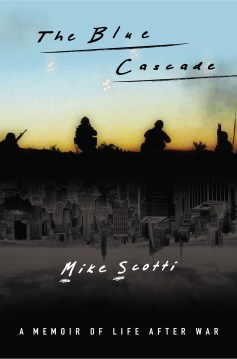

Mike Scotti served with the Marines in both Iraq and Afghanistan, and saw war’s horrors up close and personal. When he came back home, he gradually felt himself being enveloped by a growing depression and numbness he dubbed “the blue cascade.” It also ended up being the name of his book, The Blue Cascade: A Memoir of Life after War. Scotti chatted with Battleland about his story via email earlier this week:

Why did you write The Blue Cascade?

In the spring of 2010, I was touring the country with my documentary “Severe Clear” and had the opportunity to meet a lot of veterans. More than a few times, I could see clearly the darkness in the eyes of Marines and soldiers who had served in combat and were obviously struggling with the emotional aftermath of the war.

They would approach me after the event, we would chat for a bit, but I could sense that there was much more they wanted to talk about. They might not have known how to start that conversation or that I would be able to share in those feelings they were feeling so solitarily.

I knew this because I had seen the exact same darkness in my own eyes and felt those same feelings of being alone in my struggle just a few years before. So, I decided that I would tell the story of my own struggle – in a direct and completely honest way – with the hope that it would inspire others to talk about whatever it was that was bothering them. I wanted to let others know that they were not alone and that it is okay if you are not okay.

Tell us about your combat experience.

In 2003, I was a first lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps, attached to Weapons Company, First Battalion, Fourth Marines, Regimental Combat Team One, First Marine Division, as part of the initial invasion of Iraq.

I was the battalion artillery officer, coordinating the artillery missions from the forward observer teams, and at times also acting as a forward observer myself as our C.O. always commanded from a forward positions.

We attacked towards Baghdad via Route 7, with enemy engagements in An Nasiarah, As Shatrah, Al Kut, and Baghdad, among others.

Additionally, I was part of the initial invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, with Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, First Marines as part of the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit. Prior to that, I was corporal in the infantry in the USMC Reserve.

Compare and contrast your war experiences with what you experienced when you came home.

In Iraq, and in the Marine Corps in general, the norm is to focus on the good of the Corps and the men and women you serve with, never yourself. A good Marine or soldier will put the lives and safety of his buddies at a greater level of importance than his or her own.

In Iraq, I witnessed acts of extreme bravery, compassion, loyalty and honor and was led by fearless and inspiring men and women. But, in Iraq, any time you are travelling in a vehicle, the prospect that at any second your world could explode into a fiery hell of jagged shrapnel and explosive force, was a very real one.

When I first came home, the civilian world felt alien to me. I was entering into the world of high finance and found that the business world is built upon selfishness and various levels of greed. Take-take-take. Mine-mine-mine. Politicking. Gesturing. Face time.

Tom Clark

Honor was non-existent, and the level of leadership was a fraction of that I experienced in the Marine Corps. Though I was still reeling from what I experienced in the war and reports that friends who were still serving were wounded or dead, I watched as the press largely ignored the war, until it became just a dim light flickering in the background.

Though there were men and women personally touched by the war through the service of someone they cared about and I was often thanked for my service by those people and others when I was wearing a uniform, it seemed that this war I had given so much of myself to was all but forgotten.

Also, the trivial nature of every day life, with its everyday problems, seemed ridiculous to me. I would grow angry about hearing people complain about onions on their sandwich when they didn’t order them, or complaining loudly on their cell phones because the flight was delayed 30 minutes.

So many people seemed to have this overwhelming sense of entitlement. My mind would shift to visions of buddies caught at that moment, in some firefight somewhere in Iraq.

When did you first suspect you might have post-traumatic stress? When did you know it? What caused it?

I knew something was “off” even before I stepped off the plane that flew us home from Iraq. I was apprehensive about going home, even though I wanted to get out of Iraq as soon as possible.

I wanted to be home, but I didn’t want to talk to anybody, to see anybody. I just wanted to go somewhere and decompress and hide for a bit. Maybe forever.

In the days and weeks after the war, which I talk about extensively in the book, I slid down the emotional mountain.

In The Blue Cascade, I tell a story about the night of heavy drinking that turned violent and how I woke up to realize that something was definitely wrong.

About that time, I reached rock bottom and had a very real conversation with myself about whether to go for a run and “accidentally” get hit by a bus, or do a swan dive off a bridge somewhere just to end this nightmare. And I was serious.

What do you believe causes post-traumatic stress?

I believe that post-traumatic stress — from combat — is caused by seeing the horrors of prolonged combat.

For me, those horrors were mangled and contorted corpses and the faces of the dead that always seemed to have their mouths open, fearing for your life for weeks or months at a time, living in an uncertain environment in which terrible things could happen to you at any second, worrying about making mistakes that could get your buddies or civilians killed, the smell of burning flesh, the hammering of the machine guns right next to you, losing people close to you, being responsible for killing other human beings, being confused about a war whose mission and premise kept changing, and the fact that the human mind is probably not wired to endure sustained combat conditions for extended periods of time.

It throws off your brain chemistry and if you don’t fight back after you get home, it will shred your soul.

What is the one thing readers who have never been in combat don’t understand?

There is no way to describe the feeling of being watched and hunted by human beings who want to kill you. The only way to live is to kill them before they kill you. The pressure and fear is a constant undercurrent to everything you do and returning from war and getting out of that situation should be a relief, but it isn’t. That is a completely foreign experience, and unexplainable to anyone who has not felt it.

Why do you call the book “The Blue Cascade”?

The Blue Cascade is the numbness and depression that I felt when I first came home from Iraq and was floating, lost and isolated, between the two completely different worlds of combat and civilian society.

Emotionally, I was still in the war, but physically, I was in New York City. And after the numbness, came the anger and the sadness, which I imagined was cascading over the side of a cliff, crushing me as I stood on the valley floor below, looking up at it.

How did you ultimately escape?

I escaped The Blue Cascade by talking with others, in a very direct, honest and unashamed way, about my war experiences. And when I talked about the things I’d seen, and got them into the open and out from inside of me, they could no longer eat away at me. They lost their claws and teeth.

Though my situation was a bit unique, the basic process of how I opened up about the war seemed very similar to therapy. I was working with an editor and a director on the film Severe Clear, and actually re-watching many of my war experiences on a video monitor.

We reviewed every second of footage I’d shot, every picture I’d snapped and every letter I’d received. I would just start talking in a stream of consciousness, while the editor tapped away at her keyboard, capturing every word I said. I would talk about the situations we were watching, the emotions I felt, the outcomes, all of it.

At first, the process was emotionally very taxing. Almost excruciating. And things seemed to get worse for a bit. But after about five or six 12-hour editing and reviewing sessions, things starting to change I realized that it felt good to talk about these things, because I was sharing my experiences with someone else, which I think is a basic human need. One, I think, that is important.