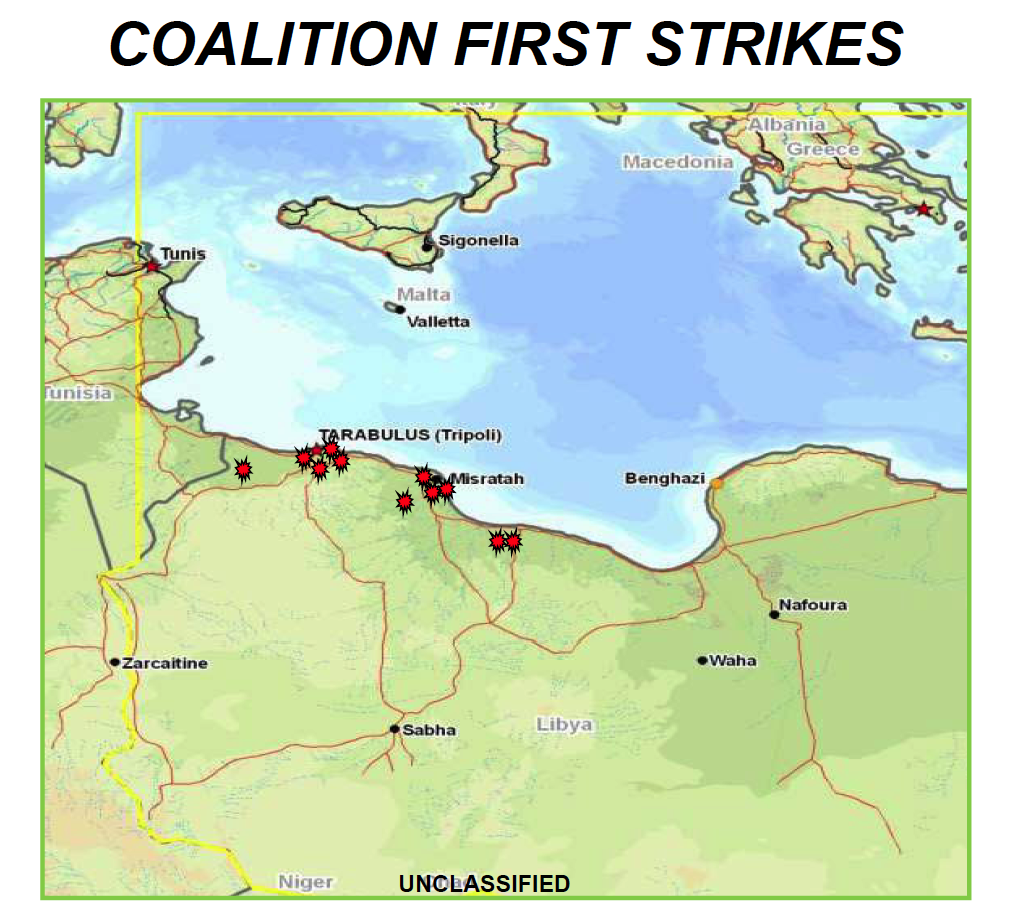

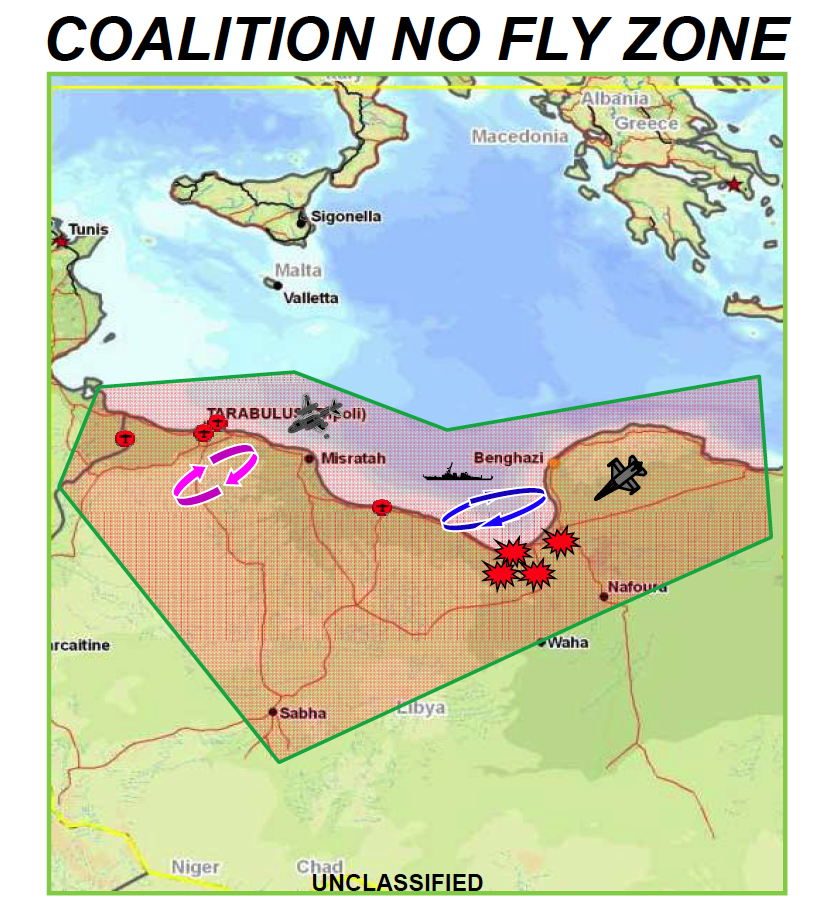

The familiar trajectory of establishing a no-fly zone was confirmed anew Sunday morning, as U.S. defense officials declared U.S. and allied forces have degraded Libya’s air-defense network, even as attacks continue against surviving pieces of his plane-killing apparatus.

Nineteen U.S. warplanes on Sunday morning followed up on Saturday’s Tomahawk strikes. Everything from Air Force B-2 bombers, to F-15 and F-16 fighter-bombers, to ship-based Marine AV-8B Harrier jump-jets, hammered assorted Libyan targets, U.S. officials said. Four British Tornado jets also participated. Navy EA-18 Growlers scrambled Libyan electronic communications by to keep the skies as safe as possible for the bombing runs.

Adm. Mike Mullen said “operations yesterday went very well” on NBC’s Meet the Press. “I would say the no-fly zone is effectively in place,” Mullen added on CNN’s State of the Union. Vice Adm. William Gortney, director of the Pentagon’s joint staff, stressed at a Saturday briefing that no U.S. troops are on Libyan soil to help guide bombs to their aim points. “There has been no U.S. forces on the ground to do the targeting,” he said. “We don’t require people on the ground to develop the targets for the target.” Libyan TV said 48 people had been killed, and more than 150 wounded in the allied strikes. Mullen told CNN: “I’ve seen no reports of significant civilian casualties.”

Gaddafi, huddled in some bunker somewhere, telephoned Libyan television and declared the strikes were launched against his nation by “the new Nazis” and pledged “a long-drawn war.” He denounced the allied force as “terrorists” attacking a nation that did nothing to warrant such action. “You have proven to the world that you are not civilized, that you are terrorists — animals attacking a safe nation that did nothing against you.”

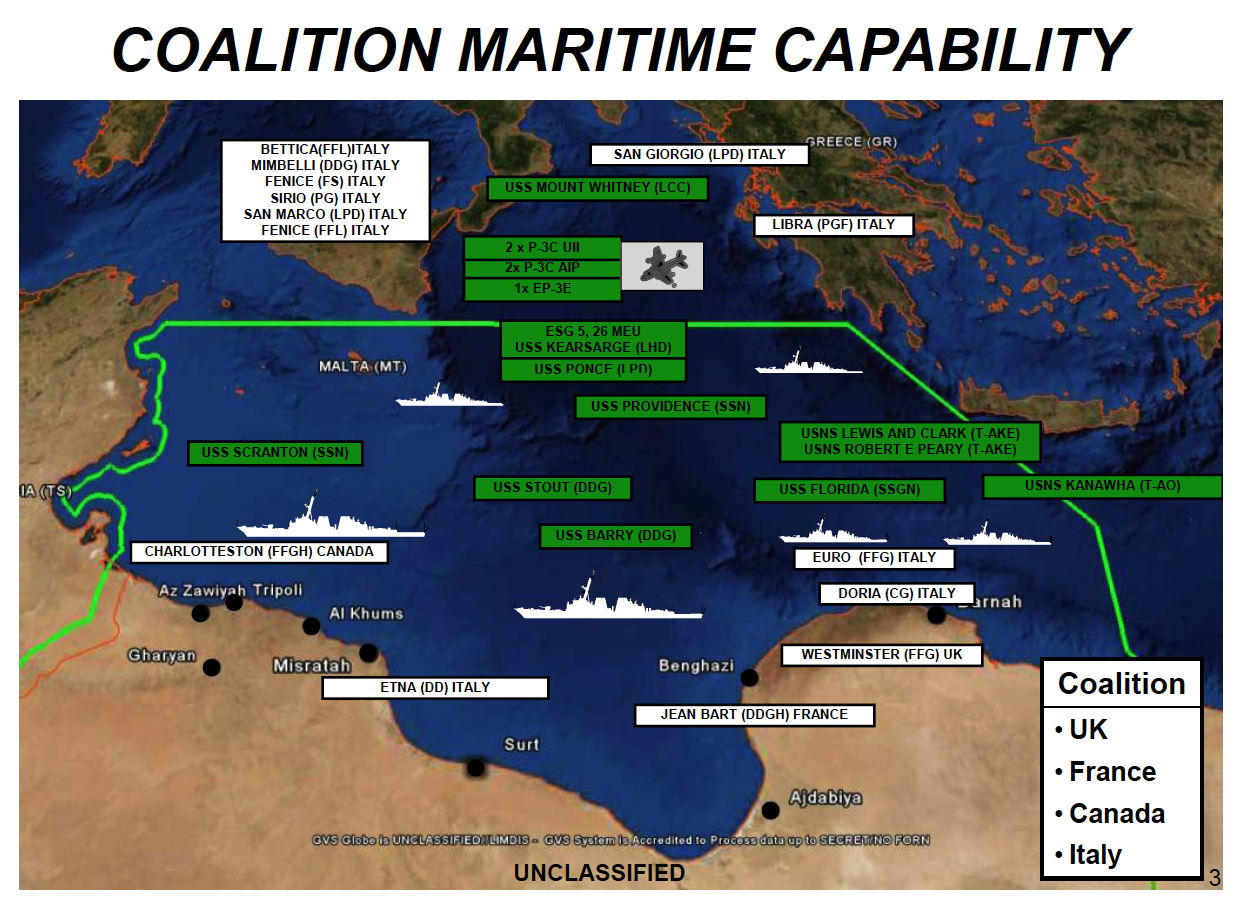

The U.S., for its part, has made clear its involvement in the conflict’s opening phase will be followed by a smaller, supporting role, as it lets France, Britain and Arab nations do the bulk of the fighting after the no-fly zone is fully in place. “We are on the leading edge of coalition operations where the United States…is in charge,” Gortney said. “In the coming days we intend to transition it to a coalition command.” But no Arab state has yet acknowledged playing a role in the two days’ worth of strikes.

Even as uncertainty about the mission’s outcome continued to bubble inside military and national-security circles, those commanding it seem united on one point: its goal is not to remove Gaddafi from power. It seems a strange objective to agree on, but Mullen said Gaddafi’s continued hold on power is “certainly potentially one outcome.” French Foreign Minister Alain Juppe, asked if the bombings are meant to drive Gaddafi from power, responded: “No. The plan is to help Libyans choose their future.”

Gortney also made clear that the allied campaign isn’t designed to cut off Gaddafi’s personal communication links, and said “no” when asked if that were part of the mission. “We’re focusing on the command and control of the integrated air and missile defense system,” he said.

Allowing Gaddafi to remain in power – after President Obama declared on March 3 that he “must leave” – seems likely only to prolong the confrontation. U.S. officials suggest the public declarations that Gaddafi’s ouster is not a goal of the Operational Odyssey Dawn gives the Libyan leader some wiggle room – although they’re betting he would be taken out, one way or another, by internal foes in the wake of the attacks.

As U.S. warplanes now buzzed over a third Muslim land, Obama acknowledged the danger such an operation entails. “I am deeply aware of the risks of any military action, no matter what limits we place on it,” he said Saturday. “But we can’t stand idly by when a tyrant tells his people that there will be no mercy.”

An Air Force lieutenant colonel weighed such a decision more than a decade ago, and warned future Presidents of the dangers in heading down this path. Jan-Marc Jouas authored No-Fly Zones: An Effective Use of Airpower Or Just a Lot of Noise? while a fellow at Harvard University’s Weatherhead Center for International Affairs in 1998:

The success of no-fly zones in minimizing U.S. casualties, signaling U.S. involvement, and executing U.S. policy will make them an attractive option in future scenarios – but not necessarily an easy one. The inherent danger, and thus the inherent tension, in choosing to enforce a no-fly zone lies in the unpredictable outcome of this policy. A political situation which calls for a limited use of force is by nature one in which the President and his advisors face a no-choice dilemma: they must take action, but they cannot resort to overwhelming power to achieve their objectives. Yet if the sanctioned nation reacts aggressively and forcefully to the presence of foreign aircraft in their airspace – no matter how limited – a no-fly zone may rapidly escalate to full-scale hostilities – the antithesis of a policy of limited force, low risk, and minimal casualties. Policy makers, therefore face an unenviable dichotomy – they must “do something” short of war, yet, for reasons they cannot control, a limited use of force may lead to war. This potential slide into conflict must be carefully and thoroughly considered when opting for action, and when selecting a no-fly zone over other possible demonstrations or implements of national power and will – such as economic or diplomatic sanctions and censures.

Jouas is now a major general based in Hawaii, in charge of U.S. Air Force operations over the Pacific. So he apparently knows what he’s talking about.